Pushing back the tide of infodemic

Among havocs wreaked by the coronavirus pandemic, infodemics—information epidemics marked by rapid spread of rumours, fake news and misinformation—could take us further down the spiral by sowing distrust and fear. An archive of COVID misinformation, which is three years in the making, has recently been launched to give snapshots of bogus news items that once captured people’s imagination, and inform researches in the field.

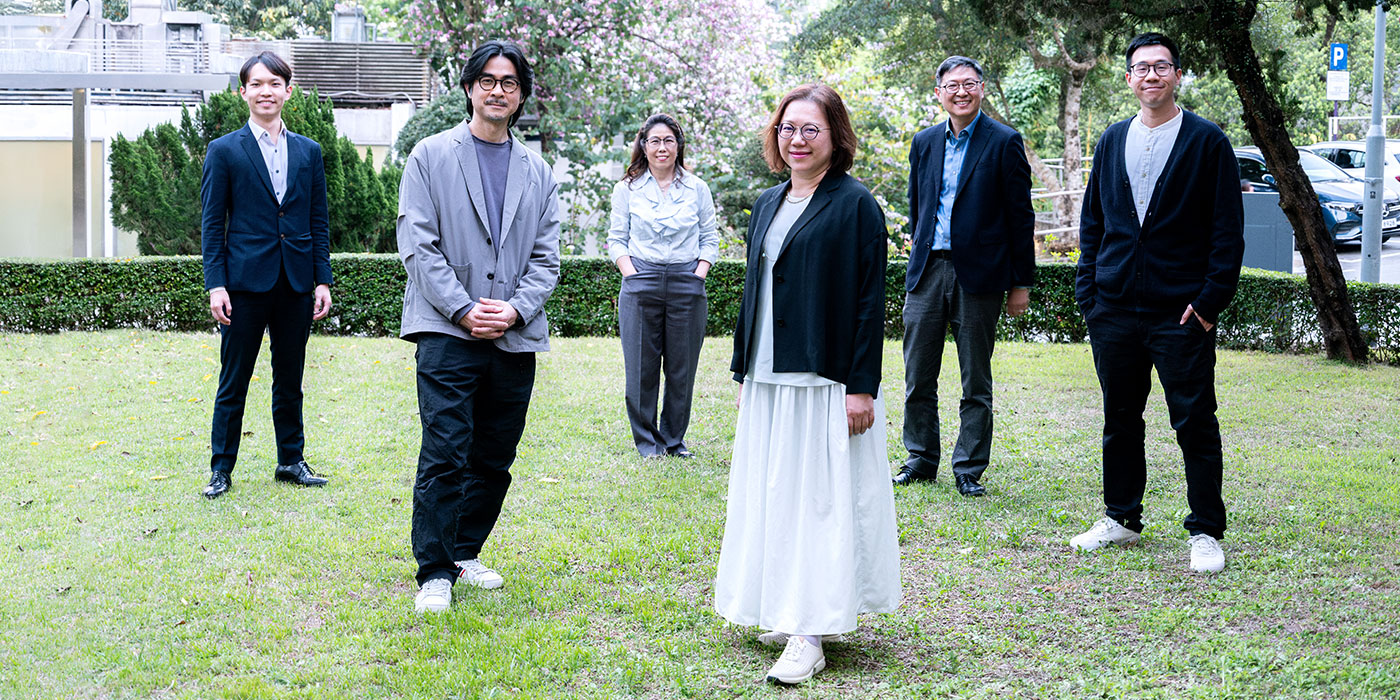

Compiled by a team led by Professor Wei Ran at the School of Journalism and Communication over the past three years, the archive forms an integral part of a Collaborative Research Fund project and is by far the largest Chinese pandemic misinformation database. Working like a Google search engine, it allows one to search pandemic-related Weibo posts from January 2020 through February 2022. Through inputting keywords like “drinking tea”, “garlic”, or “America” and “laboratory”, relevant entries will appear, and clicking on them will lead one to the posts, with their content, comments, and number of likes and shares clearly listed.

The team initially planned to include Facebook and Twitter posts, but the attempt went abortive due to access and business issues.

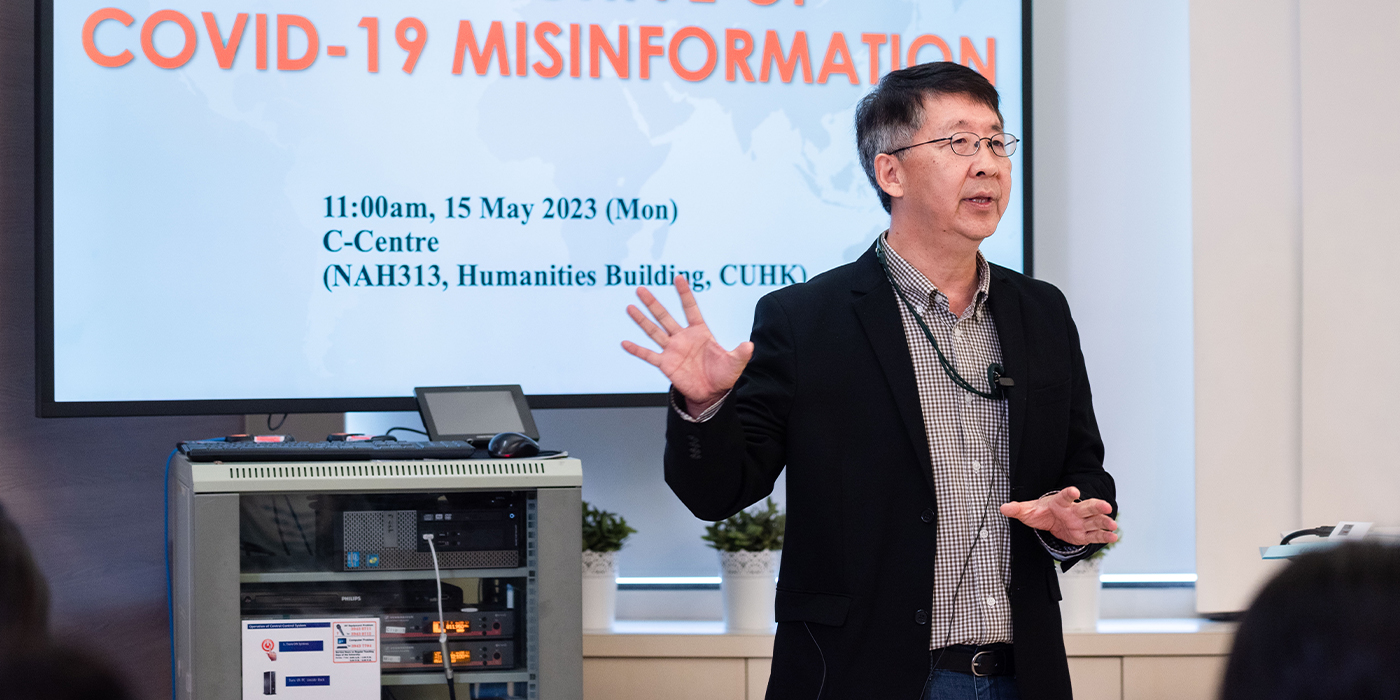

“The idea for this project was kindled by our observations and previous research on the travails and confusions caused by communications about this large-scale global pandemic. As a result of this, we were less able to deal with the crisis and were burdened psychologically and physically to cope with the extra hardship over the past three years,” said Professor Wei at the database launch in mid-May.

“It is important we capture those pieces of information, so that people in the future know what kind of information was circulated,” said he, adding many false statements were a repeat of what we had for the SARS outbreak in 2003.

The compilation process of the false news archive is an elaborate one: near 3,000 rumourous stories were first identified based on debunking narratives by two professional Chinese fact-checking platforms. Keywords were gleaned from these stories, which were in turn used by DMDI Insights, the School’s social media data collection and processing platform, to crawl the web and find out more than 280,000 Weibo posts. The posts were sieved with the help of AI and manually, finally yielding near 200,000 posts which make up the database proper.

“In social psychology, we have a concept called the need for cognitive closure, which refers to the human desire for epistemic security. When we face uncertainty, the first thing we want to have is the feeling that we really know something,” said Professor Chiu Chi-yue, dean of social science, in his opening remarks at the launch. He explained that when people have seized some knowledge as the basis for resolving their uncertainty, they will freeze on that and become unamenable to persuasion and change.

“During the pandemic, people faced a lot of uncertainty and the need for epistemic certainty was high. It is so important that people have at their fingertips reliable and accurate information, because without that, people will just use that [the misinformation] to solve uncertainty and will become very resistant to information updates,” Professor Chiu added.

Professor Donna Chu, School director, noted on the same occasion that the database is a rich trove of examples of fake news and rumours, which she may tap into for her media literacy workshops.

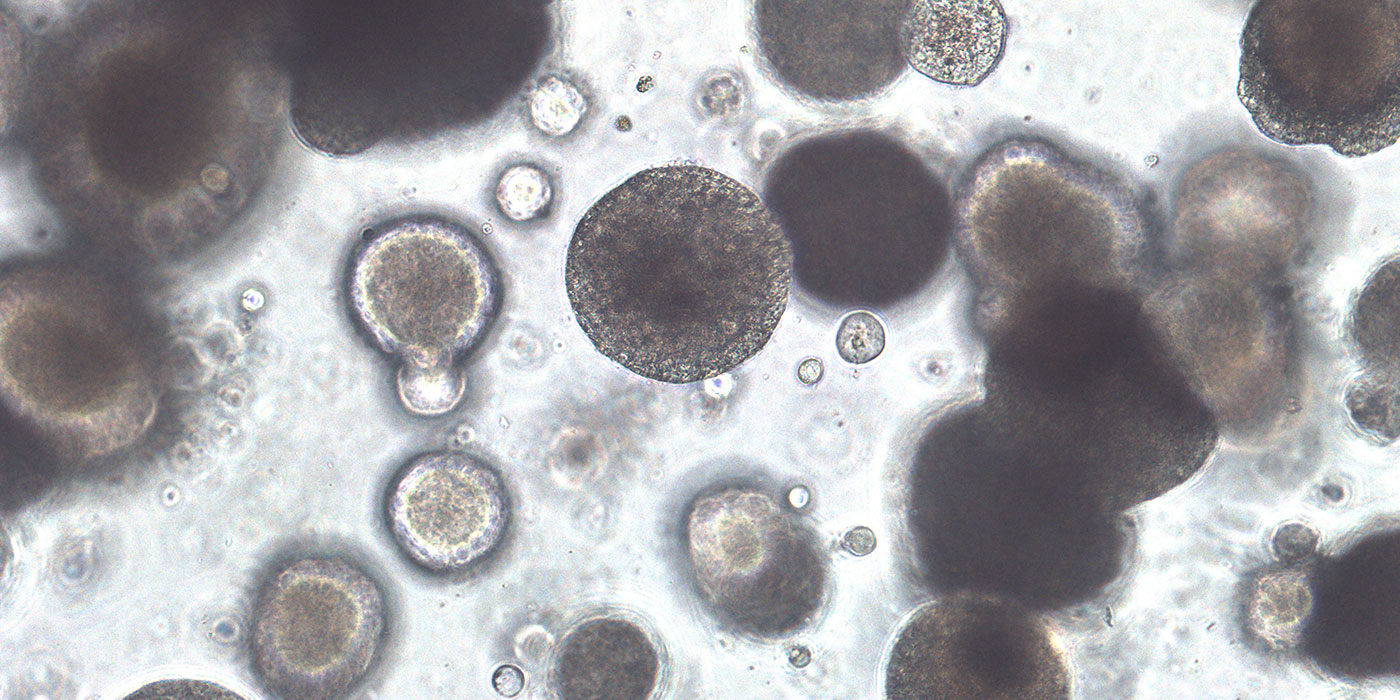

During the launch at the School’s C-Centre, Professor Wei also pointed out the hoaxes can be roughly divided into three categories: the first is traditional medicine and food considered efficacious in curing the plague. The second concerns origins of the virus, where conspiracy theories abound. The last bears on government policies: is there a lockdown or mass testing? Is supply of face masks and food sufficient?

“This type of misinformation turned out to be more damaging and destructive because it unleashed panic. It affected people’s behaviour and understanding of the situation—that it would threaten their livelihood and health,” said the professor who has studied media effects for three decades.

By Amy Li

Photos courtesy of School of Journalism and Communication