Zest for the qin legacy

Expert conservator breathes new life into the 700-year-old instrument

The CUHK Art Museum is a veritable treasure trove. One of its gems is a qin (a plucked seven-string Chinese instrument, also known as a zither with seven strings) created in the Zhongni, or Confucian, style. It was crafted between the Southern Song and early Ming dynasties.

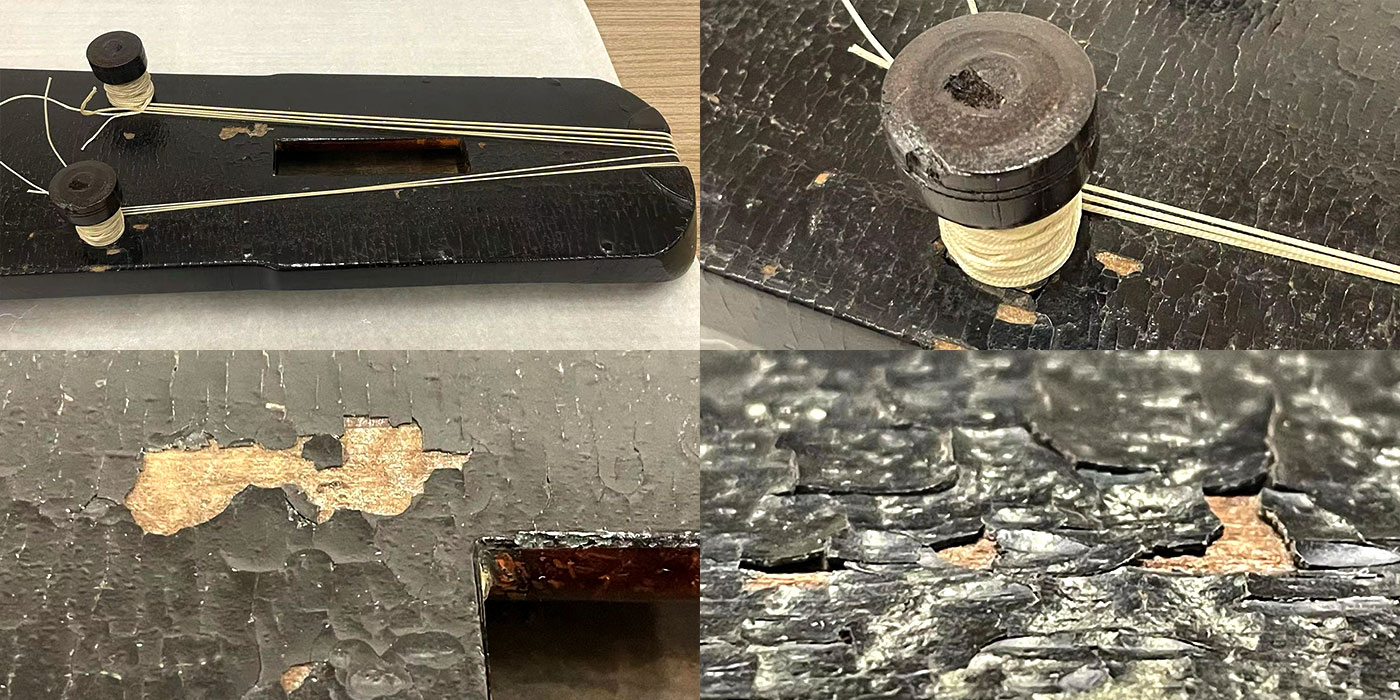

Heritage and exquisiteness are the twin hallmarks of this gift from one of the Art Museum’s long-running supporters, Bei Shan Tang, a private studio of the late Dr Lee Jung-sen that houses an extensive collection of Chinese art pieces and antiquities. The qin is made of natural materials, with a paulownia-wood top and a catalpa-wood bottom. Entirely coated in black lacquer, its surface is a mix of natural cracks called “snake skin” and “ox hair”, exuding an elegant aura of antiquity.

Guqin in Zhongni (Confucian) style

Late Song to early Ming dynasty (13th-14th century)

Acc. no.: 1999.0536

Gift of Bei Shan Tang

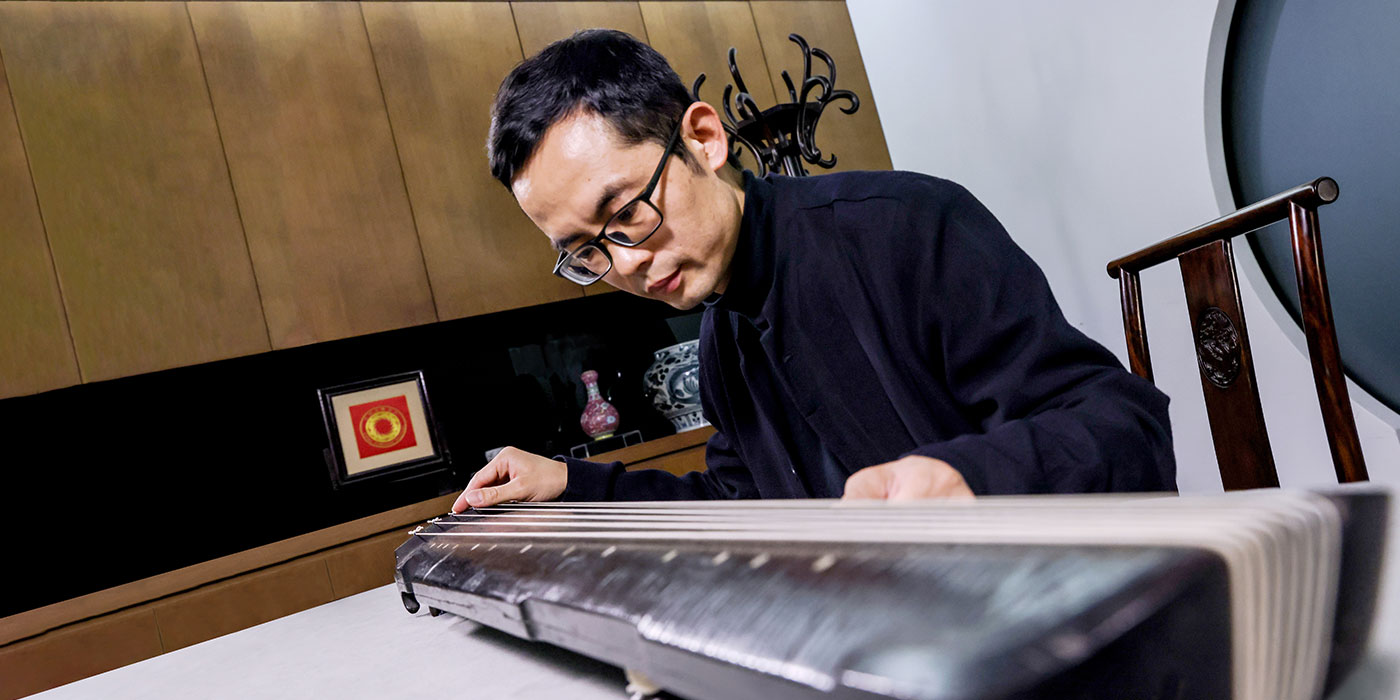

A professional in action

As a relic of 700 years, the qin had more than 20 flaws that warranted expert repair skills. CUHK seized the opportunity when Mr Min Junrong, a professional lacquerware conservator from The Palace Museum in Beijing, visited the University’s renowned Art Museum in February.

Art Museum Director Professor Josh Yiu, knowing the conservator’s interest and expertise in qin, drew his attention to the problematic condition on the underside. “Mr Min, would you like to conserve this qin during your short stay here in Hong Kong?” he asked.

“No problem,” said the latter, accepting the Art Museum’s request on the spot.

Professor Yiu arranged for the qin to be removed from the gallery walls. Min listened to qin master Mr Sou Si-tai and his students play on the instrument, then proposed taking on the repairs after office hours. Painting Conservators of the Art Museum volunteered to keep him company while he worked.

True to his name, Min had the steady, dexterous hands of a conservator, fixing the 20-odd flaws over five evenings in the last days of the Year of the Rabbit on the lunar calendar. To the Art Museum’s expression of gratitude for his voluntary service, Min replied modestly that it was his honour to conserve such a moving piece of instrument.

He wrote: “The studies into qin are just as important as the applications of the instrument; only custodians who understand the responsibility at hand can fulfil the latter, and breathe new life into these artefacts.”

Road to mastery

Min graduated from the Department of Arts and Craft at Tsinghua University in 2004, specialising in lacquer craft. He joined the Department of Conservation Science as a lacquerware conservator assigned to Beijing’s Palace Museum. At that time, he was unversed in the art of qin.

“I knew nothing about this prestigious instrument, not even the basic playing skills. Those days were therefore quite stressful,” Min tells CUHK in Focus.

“When I first joined the museum, I worked on the conservation of artefacts that originated in zhonghe shaoyue,” he says, referring to Chinese imperial ritual music of the Ming and Qing dynasties. “Interestingly, it was my teacher who was working on qin conservation. I was given the opportunity to learn from him a year later. That was my first encounter with the qin.”

To complete each conservation project well, Min also learnt from qin players and qin-making masters, broadening his understanding of the centuries-old instrument in the process. “We also learnt from expert Zheng Minzhong, who oversaw the research and conservation of qin at the Palace Museum.”

He continues: “Qin made in different dynasties do not share the same style or timbre. Therefore, it is vital to study the background of each qin before conservation. I underwent a gradual learning process starting from the Qing dynasty, and then to the Song and Tang dynasties.”

After years of blood, sweat and tears, Min has matured into a qin conservator who is recognised by many.

Wisdom of the past

While musical instrument relics and general lacquerware share similarities in craftmanship, conservation calls for many specific requirements that are unique to the task. Min explains: “One of the most pivotal principles is to minimise intervention for the sake of effective protection. As conservators, we work on only defective parts of an artefact, and strive to preserve as many traces of history as possible.”

Given his passion about reviving the past, Min places emphasis on “maximum retention”, that is, not trying to conceal the oldness of the antique.

“Artefacts offer a unique glimpse into the past, and we can uncover stories of the people who came before us. We have to ensure that the restored parts are consistent with the artefact’s original craftmanship, materials, decorative features and style.

“For instance, the lacquer layer and other coatings used in qin conservation are the same as those used in crafting the qin.”

As an example, he cites the newly repaired Art Museum qin, which was showing signs of missing lacquer and protective layers. Lacquer, a liquid that is painted on wood or metal and forms a hard, shiny surface when it dries, had also been separated from the qin body in the yanzu (also known as the goose feet) area, around which the strings were coiled.

“Therefore, the conservation of this qin mainly focused on fixing areas around the yanzu and towards the tail,” says Min. “I mixed lujiaoshuang with lacquer to restore the protective layer, so that strings can be wrapped around and secured properly.” Lujiaoshuang is a commonly used material in qin conservation.

The choice of material is very important as it determines whether the restored qin can produce sounds and allow the strings to vibrate the same way it is supposed to. “From material selection to the craft of qin making, it is of no doubt that the past holds the true wisdom. My mission as a conservator is to preserve this craft and pass it on.”

Tranquillity on seven strings

Dutch orientalist and qin musician Robert Hans van Gulik describes the solo qin as “the great instrument of the Holy Kings” in his book, The Lore of the Chinese Lute. From open string to overtone and pressing string, each tone is elegant and unique in itself alongside beautiful melodic lines. The qin enjoys great prestige among Chinese literati, being inseparable from Chinese literature, painting and poetry. “Qin music nourishes one’s temperament. It connects with one’s body, mind and soul,” says Min.

In honour of its priceless gift, the CUHK Art Museum is displaying the beautifully crafted qin in the exhibition, “When Art Speaks: Treasures of CUHK”. The exhibition runs until 5 May and is open to the public free of charge.

By Gillian Cheng

Photos by D. Lee