Food for thought

Professor Rocky S. Tuan and the Venerable Kuan Yun ponder the intersection of Buddhism and biomedicine

The intricate and fascinating relationship between science and Buddhism was explored in a thought-provoking dialogue on 27 March between Vice-Chancellor and President Professor Rocky S. Tuan and the Venerable Kuan Yun, Chairman of the Hong Kong Buddhist Association, Abbot of the Western Monastery and Secretary-General of Tsz Shan Monastery. They shared views on the ethics of animal tests, euthanasia and in vitro fertilisation (IVF).

“In Dialogue with Ven Kuan Yun – Buddhism and Biomedicine” drew 200 people to Lee Hysan Concert Hall, as well as 160 viewers to the live broadcast. The one-hour event was filled with wisdom and humour. The Venerable Kuan Yun cited Albert Einstein’s quotation, “science without religion is lame; religion without science is blind”, and expressed hope that Buddhist wisdom would enlighten and guide scientists throughout their research and journey of innovation.

Professor Tuan, himself a renowned biomedical scientist, added: “Even if we have made great contributions to humanity, it does not mean that what we do is completely correct. Our starting point and principles should be in line with religious values.”

Science and religion in harmony and divergence

Biotechnology and artificial intelligence might be improving human life and biomedical research, but had also resulted in many ethical, legal and social questions. This was where religion came in, according to the Venerable Kuan Yun; science and religion complemented each other, and Buddhism was a faith that responded to the times. Its wisdom held the potential to inspire scientific progress.

He further said that science and Buddhism shared a common concern for the universe and human existence. “How does Buddhism respond to the era? More than 2,500 years ago, Shakyamuni Buddha gave a profound interpretation based on the concept of dependent origination,” he said. “Dependency is about conditions. Causes and conditions are interrelated. It is said that ‘the fruit arises from the cause’. Different causes give rise to different consequences.”

Innovative therapies were developed through clinical trials. Scientists often used animals such as mice for experiments, leading to ethical concerns about animal welfare. The Venerable Kuan Yun noted that all experiments aimed at preventing human suffering, but people should adhere to the principle, “Whatever is disagreeable to yourself, do not do unto others”, and maintain a harmonious relationship with nature. No one is an island; on the contrary, people all relied on one another and found warmth in connections with other people. Everyone should coexist peacefully with nature and the animal world, he said.

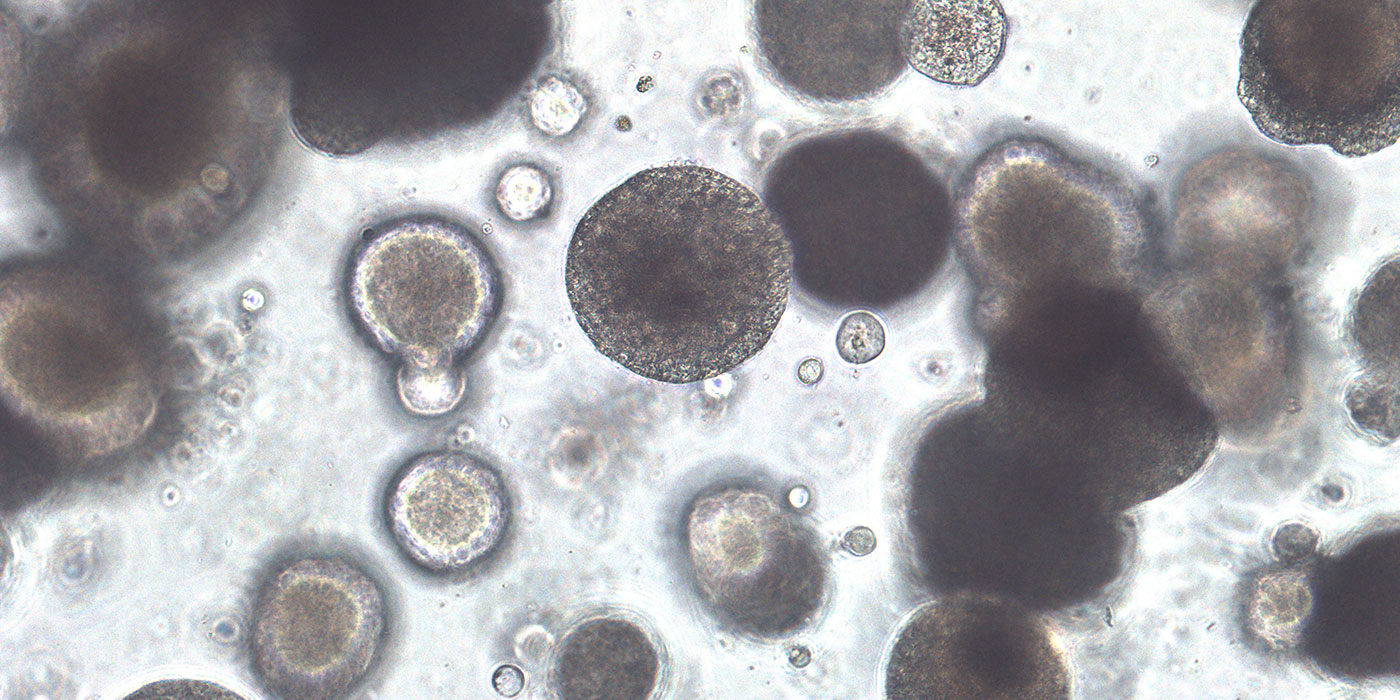

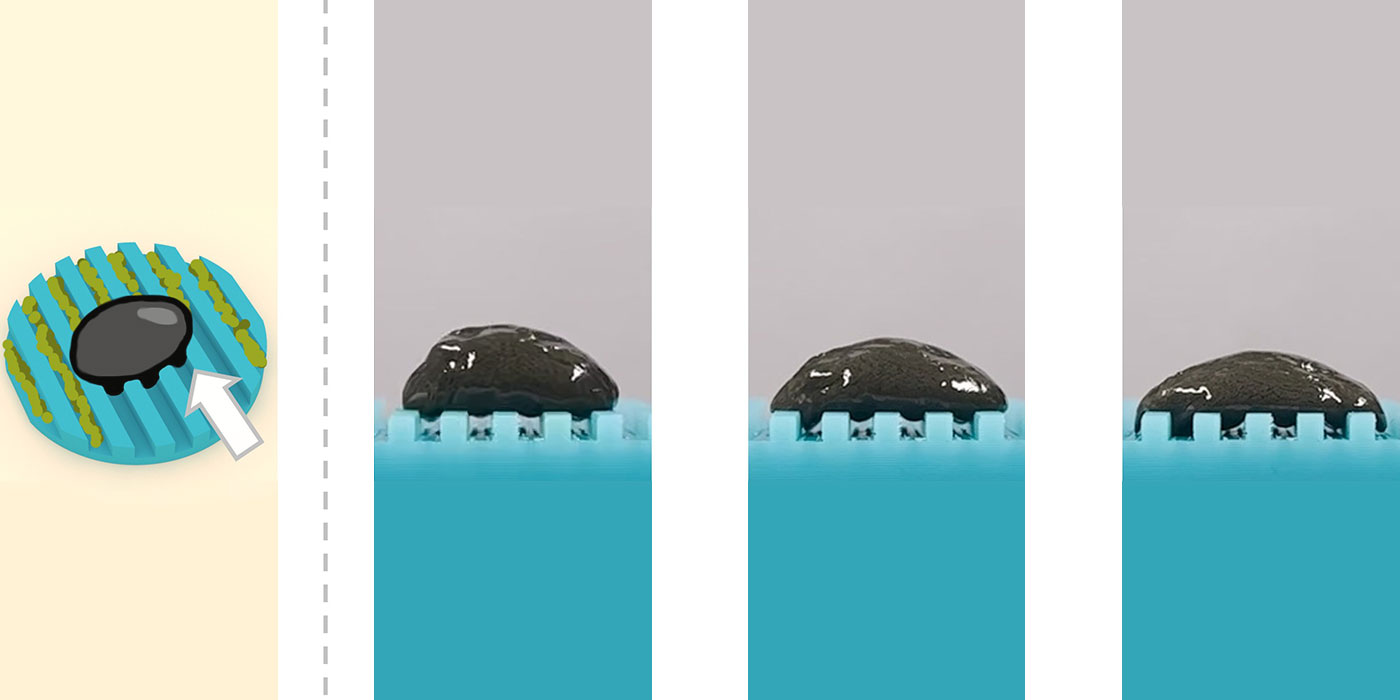

Professor Tuan gave his take on animal testing by noting that scientists were studying organoids to simulate the functions of human organs. The hope was that organoids would one day replace the usage of animals.

“Animals are not inferior. We are just unwilling to use living humans as subjects for experimentation,” he said. “Since we avoid conducting experiments on living humans, we explore how to extract stem cells from the human body and aggregate them into organoids, such as hearts and lungs. These organoids can then be used to test the safety of drugs and vaccines before experiments are conducted on living humans. Stem cells are not lives, so there is no issue of killing.”

The bearable lightness of being

Both men moved on to the topic of euthanasia, which in Chinese is called “dying in comfort”. Science and religion adopted different approaches to the human life cycle. The Venerable Kuan Yun pointed out that comfort, happiness and suffering were all relative in nature, just as high and low were also relative.

He spoke about the Buddhist teachings of the concept of illusion in “dependent origination”, “mutual dependence” and “permanence”. Everything in the universe lacked inherent existence, having originated in a combination of conditions and ultimately melting away into nothingness.

Human cognition was limited, he said, quoting the saying: “A human does not see the wind, nor fish the water.” The same water could carry many interpretations, as reflected in another saying: “Buddha looked at a bowl of water and saw 84,000 organisms.” The notion of “four perceptions arising from the same water” had a similar meaning: to Heaven, the water was a precious adornment; to humans, clear water; to fish, a dwelling place, and to ghosts, pus and blood. The external world was absent of intrinsic existence and dependent on human cognition, he said, explaining why any form of joy was ultimately incomplete and transient.

For Professor Tuan, euthanasia could be understood from the life cycle of cells. “Thirty to forty years ago, scientists discovered that cells had self-defence mechanisms. Depending on factors such as the environment and age, cells had their own way of dying and regenerating. At a certain point, cells would naturally end their existence,” he said.

“The same applies to euthanasia. When every cell in the human body approaches the end, doctors have two choices: one is to prevent this situation from occurring by prolonging the patient’s survival and preventing them from dying; the other is to respect the patient’s wishes and allow them to depart peacefully without prolonging their suffering.”

The professor acknowledged that he found it hard to juggle between active intervention to keep the patient alive and enduring the pain, and letting them go, which could be the moral thing to do.

Nurturing life

From talking about death, the two men moved on to discussing life. In 1978, the world’s first test-tube baby was born. Since the advent of this technology, countless infertile couples had conceived children, but people had also criticised it for defying nature.

Professor Tuan said that many unnatural things had a role to play. For instance, building a bridge over a river allowed people to cross between the two sides freely. And IVF, despite being unnatural, could help infertile couples bear children.

However, he also pointed to human epigenetic effects occurring in the womb, triggered by the impact of behaviours and the environment on how genes worked. If eggs were fertilised by technicians of assisted reproduction selecting the best embryos and implanting them instead of naturally combining with sperm in the womb, IVF might have unpredictable health problems. If babies were not born through the birth canal, they would lack probiotics, leading to weakened immunity, he said.

The Venerable Kuan Yun also felt that artificial insemination went against nature and should not be attempted. The way he saw it, it had to do with the Buddhist concepts of karma and reincarnation.

“Where do we come from? Where are we going? In Buddhism, we say that there is a process of ‘12 links of dependent origination’ in between. The 12 links of dependent origination are the 12 factors that constitute the cycle of birth and death for sentient beings,” he said. Buddha used these 12 links to explain the causes of the birth-and-death cycle and the basis for liberation from bondage to life and death.

Igniting the spark of life

In his concluding remarks, Professor Tuan expressed gratitude to the Venerable Kuan Yun for sharing insightful perspectives with the audience. He voiced hope that the dialogue would inspire exploration and contemplation of the intersection between religion and science.

“The experiences and realisations of life from venerable figures in Buddhism over the past 2,000 years have consoled our souls and inspired the development of biomedicine, especially in the ethics and morals of medical research, the application of medical technology and the provision of palliative care,” he said.

“There is much that the Buddhist and biomedical research communities can learn from each other. This type of interdisciplinary dialogue, which examines the nexus between the spiritual and scientific worlds, is exactly the kind of rich cultural and intellectual tapestry we hope to forge at CUHK.”

By Jenny Lau