Bookshelves of CUHK

“Books are a uniquely portable magic,” said novelist Stephen King when asked about the wonders of reading. We can never travel to every part of the world, nor can we experience every possible lifestyle—but reading makes everything possible. For CUHK professors who might have been one of your course instructors, reading books outside their own disciplines opens the doors to treasure. Three professors share their thoughts on reading in the second part of Bookshelves of CUHK series.

Professor Chiu Chi-yue, Dean of Social Science

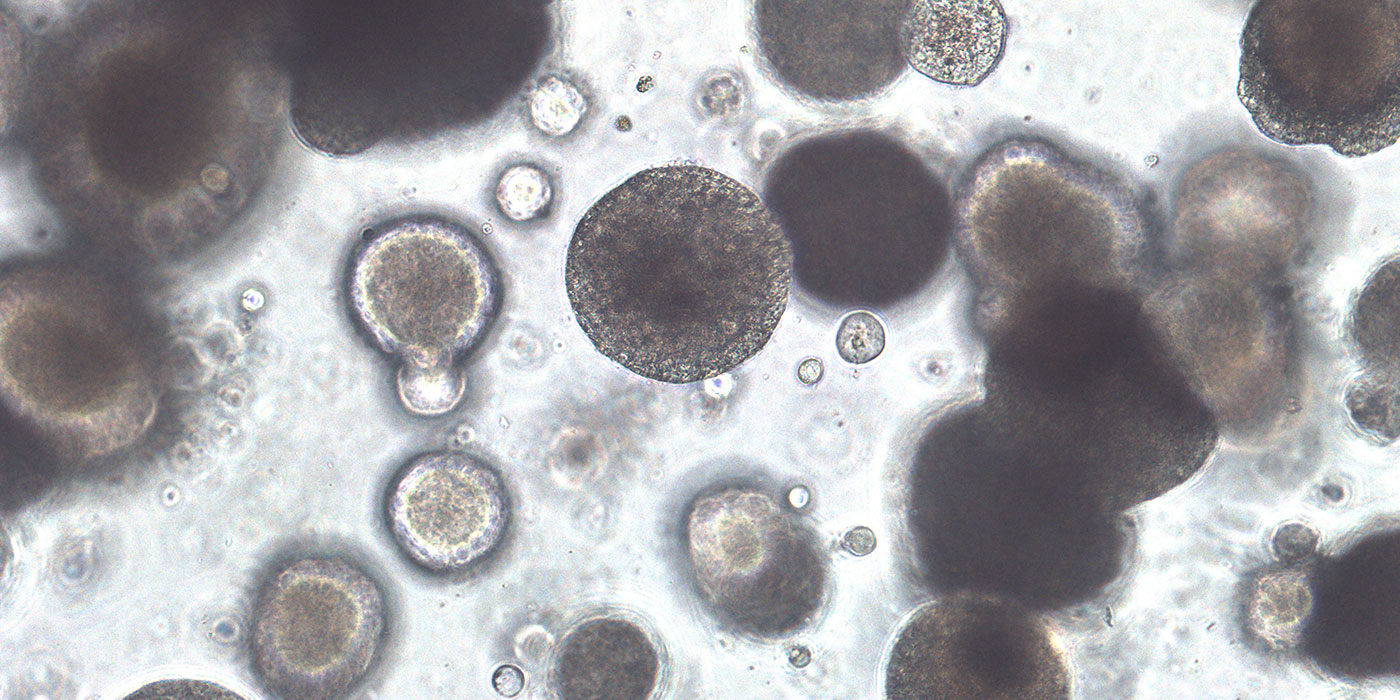

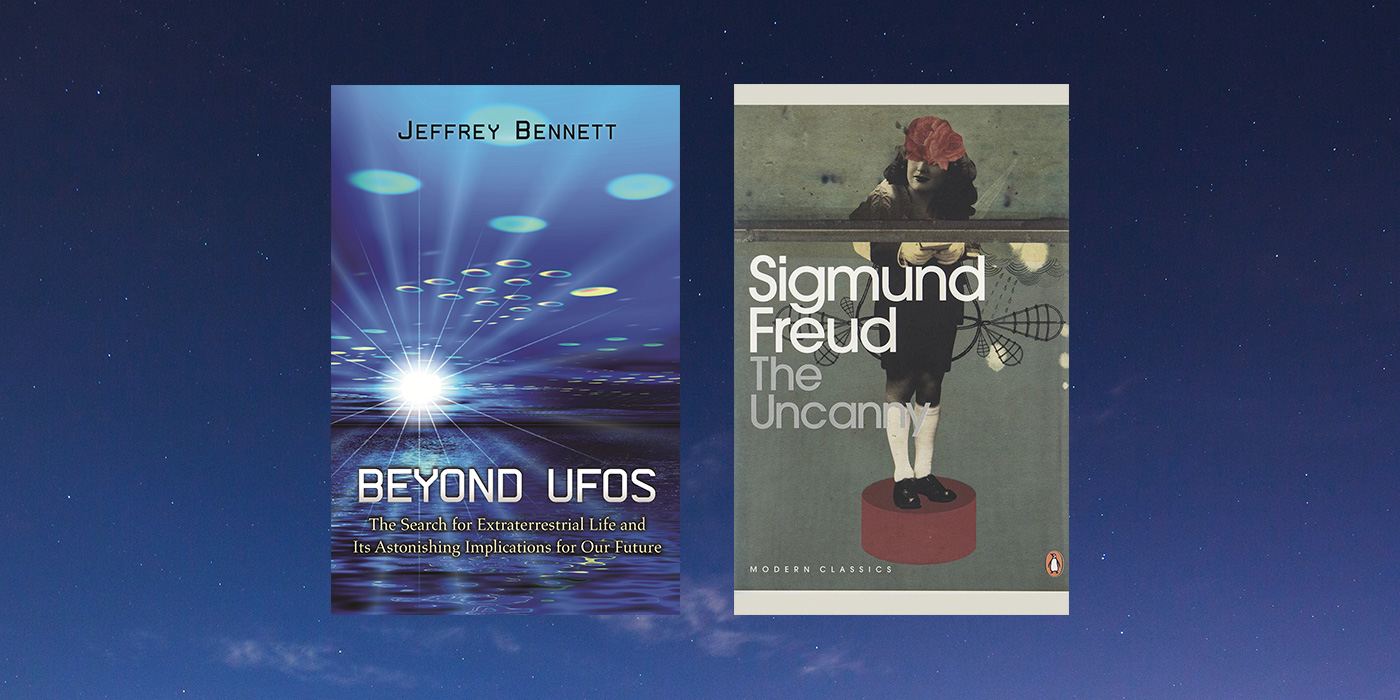

I bought Beyond UFOs: The Search for Extraterrestrial Life and Its Astonishing Implications for Our Future by astronomer Dr Jeffrey Bennett from a bookstore in Los Angeles. The book communicates the excitement of the new interdisciplinary science of astrobiology, which blends astronomy, biology and geology to explore the possibility of extraterrestrial life. It also inspires reflections on what life is and what makes our planet inhabitable. Since then, the chapter “What makes it science?” has become assigned reading in my graduate behavioural science research methodology class. From it, my students learn how science can help people come to agreement. As Dr Bennett puts it, “Instead of trying to convince you that aliens exist by telling you what I saw with my eyes, I need to go about it by concentrating on evidence that we can examine together… Only through science will we actually learn something about other life in the universe, if indeed it exists.”

I bought Beyond UFOs: The Search for Extraterrestrial Life and Its Astonishing Implications for Our Future by astronomer Dr Jeffrey Bennett from a bookstore in Los Angeles. The book communicates the excitement of the new interdisciplinary science of astrobiology, which blends astronomy, biology and geology to explore the possibility of extraterrestrial life. It also inspires reflections on what life is and what makes our planet inhabitable. Since then, the chapter “What makes it science?” has become assigned reading in my graduate behavioural science research methodology class. From it, my students learn how science can help people come to agreement. As Dr Bennett puts it, “Instead of trying to convince you that aliens exist by telling you what I saw with my eyes, I need to go about it by concentrating on evidence that we can examine together… Only through science will we actually learn something about other life in the universe, if indeed it exists.”

The article “Why do people believe in ghosts?” in The Atlantic reveals that a sizable percentage of highly educated people still believe in ghosts despite the rise of science, scepticism, secularism and public education. My subsequent literature review confirms the insufficiency of our scientific knowledge about human’s persistent belief in ghosts. In Sigmund Freud’s The Uncanny, he offers several provocative hypotheses why, when it comes to this uncanny topic, “practically all of us (including the most able and penetrating minds among us)” still think in the same way as people without access to education.

I read whatever I am curious about. More often than not, inspiration comes to me not from the text but from the connections I build between it and my life experiences, including prior reading experiences. This active and interactive reading process is what turns a story in the text into a never-ending story.

Professor Philip Chiu, Associate Dean (External Affairs) of Medicine

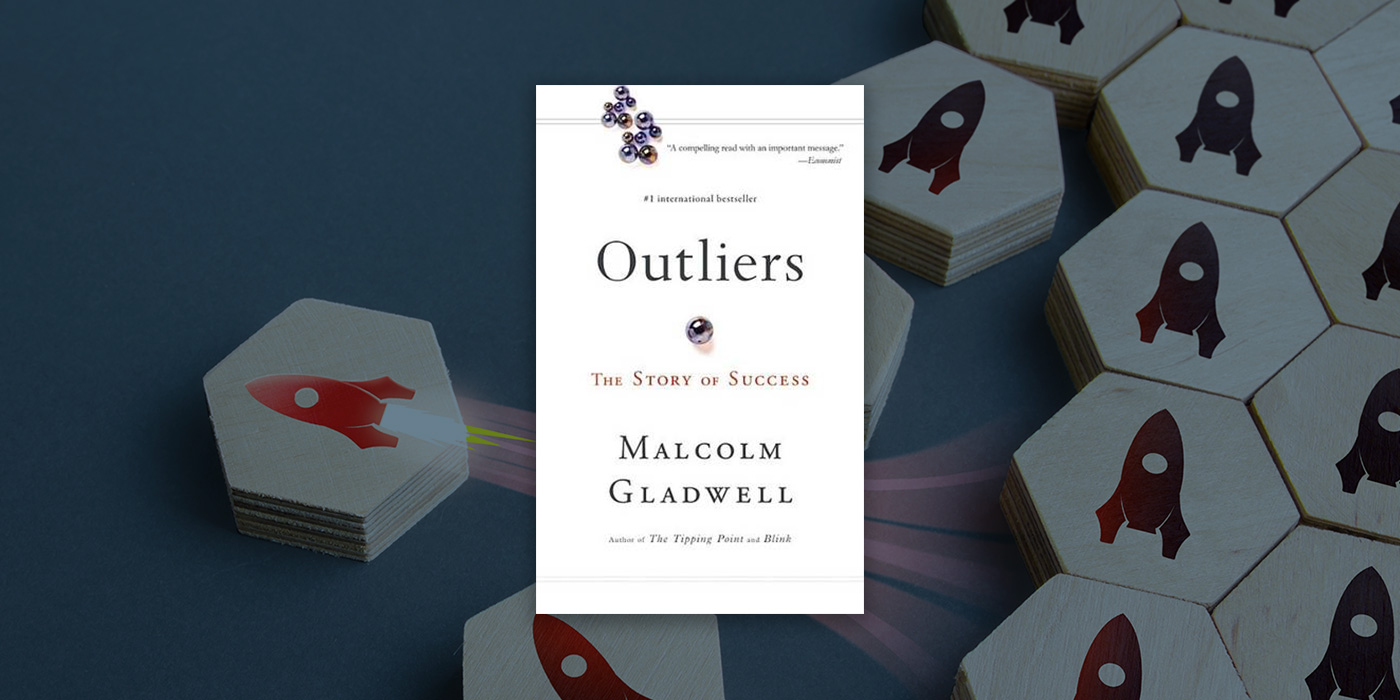

Success depends not only on talents we are born with. In this book, Malcolm Gladwell suggests that achieving true expertise in any skill is a matter of practising for at least 10,000 hours. Before the success of the Beatles, they played and perfected their songs live in Hamburg over 1,200 times from 1960 to 1964.

Success depends not only on talents we are born with. In this book, Malcolm Gladwell suggests that achieving true expertise in any skill is a matter of practising for at least 10,000 hours. Before the success of the Beatles, they played and perfected their songs live in Hamburg over 1,200 times from 1960 to 1964.

Professor Lewis Terman is best known for his longitudinal study of children with high IQs. Though most of the high IQ children have excellent achievements, the relationship between success and IQ works only up to a certain point. Gladwell argues that a mature scientist with an IQ of 130 is as likely to win a Nobel Prize as one whose IQ is 180.

Practising medicine requires a certain level of intelligence to understand the scientific basis of diseases and their treatments. However, a good doctor requires elements beyond knowledge. A good doctor should be an empathetic listener who understands patients’ suffering and a good communicator who elaborates on diagnosis and treatment options. In Gladwell’s words, these essential qualities are “practical intelligence”.

Albert Einstein once wrote on the blackboard in his office: “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.” I trust that one of the important aspirations for academics is to educate and train successful undergraduate and postgraduate students. Outliers: The Story of Success reveals that we should not only impart knowledge, but also inspire our students with what truly matters, such as perseverance and team spirit.

Professor Ho Che-wah, Choh-Ming Li Professor of Chinese Language and Literature

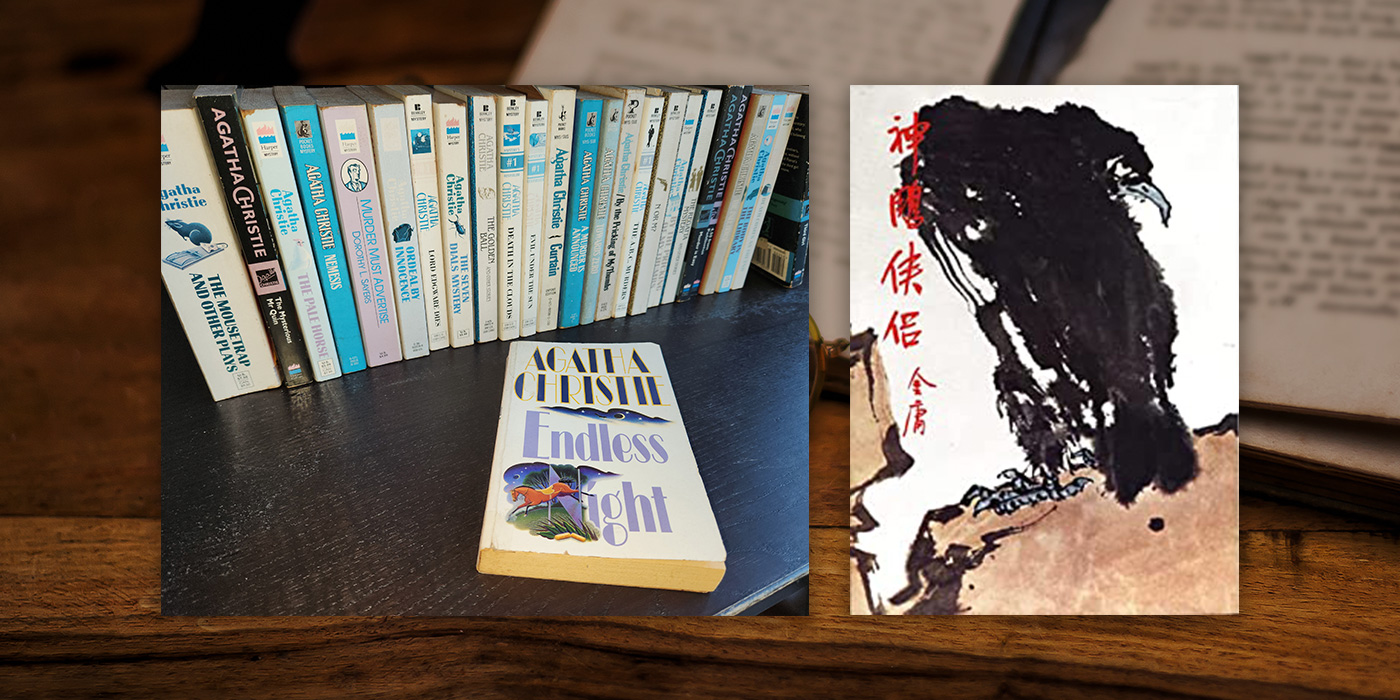

My teaching and research focus on textual analysis of ancient Chinese classics written in the Spring and Autumn period (770–476 BCE), the Warring States period (476–221 BCE) and the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Whenever I want to take a break from my rigorous research work, I read interesting literary works to unwind. The works of 20th century British detective novelist Agatha Christie and Louis Cha’s martial arts novels are on my list. I started reading Christie’s novels as an undergraduate and I love reading Cha’s books when I go abroad. I find Christie’s Endless Night and Cha’s The Return of the Condor Heroes (《神鵰俠侶》) most enchanting.

My teaching and research focus on textual analysis of ancient Chinese classics written in the Spring and Autumn period (770–476 BCE), the Warring States period (476–221 BCE) and the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Whenever I want to take a break from my rigorous research work, I read interesting literary works to unwind. The works of 20th century British detective novelist Agatha Christie and Louis Cha’s martial arts novels are on my list. I started reading Christie’s novels as an undergraduate and I love reading Cha’s books when I go abroad. I find Christie’s Endless Night and Cha’s The Return of the Condor Heroes (《神鵰俠侶》) most enchanting.

Endless Night is well-plotted. The protagonist Michael Rogers, who comes from a humble background, is scheming. One morning, his wife Ellie suddenly passes out while riding a horse and is found dead later on. Everything seems to be beyond doubt. Eventually, readers unravel the mystery and discover the truth amid the clues threaded through the text by Christie.

The plot of The Return of the Condor Heroes is profoundly moving. It revolves around the forbidden romance between the protagonist Yang Guo and his martial arts teacher Little Dragon Maiden. The narration is exquisite and subtle, leaving readers room for contemplation. Most readers are moved by the impermanence and fragility of the lovers’ relationship, but not many of them notice the hidden affections Guo Xiang—the youngest daughter of Yang’s uncle, who to Yang is like a father figure—to Yang Guo. In Cha’s detailed portrayal, Yang Guo unmasks himself and hands three golden pins to Guo Xiang as tokens of promise. The moment is engraved on the latter’s mind forever.

For youngsters looking to brush up on their writing, reading literary classics—and rereading them—is the way to go. With literary reading, fluency and ingenuity in writing would come to them naturally.

As told to Jenny Lau

Images designed by Matthew Wu