A Lover of Truth

Professor Richard Dawkins on believing evidence over mythology

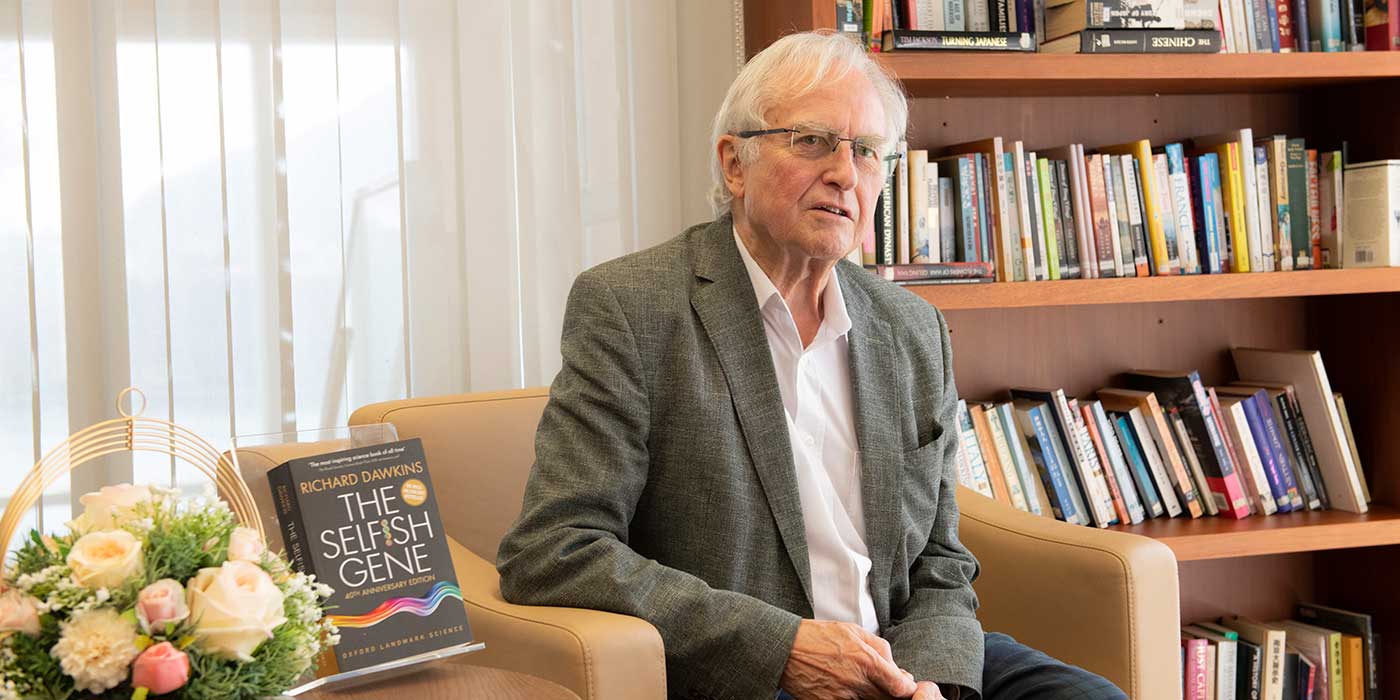

The first thing Professor Richard Dawkins does when we arrive is to gently but firmly decline our suggestion to take a few photos before the interview starts. “I insist on taking pictures during the interview”, he tells CUHK in Focus. Such insistence, manifested in politeness with an edge of steel, has been his calling card for more than half a century.

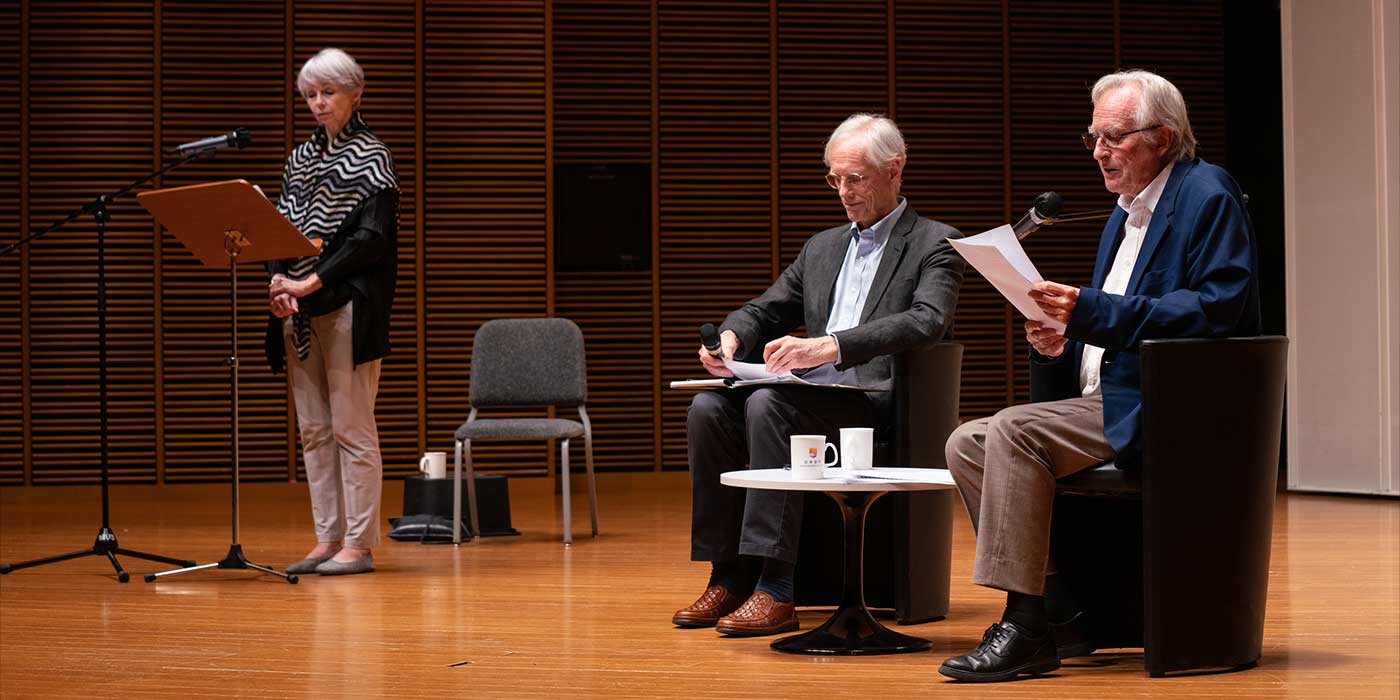

To go into a complete list of Professor Dawkins’ accomplishments would be an exhausting and ultimately futile task. Alongside an immense research career, he has devoted decades striving to make science accessible to all, including a 13-year stint as Oxford’s inaugural Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science. His international best-sellers The Selfish Gene and The God Delusion, for example, have been translated into dozens of languages and devoured by readers across the globe. Such is Professor Dawkins’ starpower that when he gave a reading of his works at CUHK last week, there were barely any empty seats in the concert hall.

After a childhood in the former British Protectorate of Nyasaland (now Malawi) in southeast Africa during the 1940s, Professor Dawkins spent his formative years in England. He attended Oundle School, a public school closely affiliated with the Church of England, before arriving at the University of Oxford to study zoology. “Here,” he enthuses in his 2013 memoir An Appetite for Wonder, “was a subject I could really think about: a subject with philosophical implications.” When pressed about the importance of this discovery, he explains that his Oxonian experiences stood in marked contrast with his secondary school life, where “it was pretty much an exercise in memorisation and learning from textbooks.”

He found learning at university to be a much more thought-provoking and eye-opening experience. “You had to write an essay by actually taking sides in a controversial issue, and that led to a more philosophical outlook. You had to learn to think, to argue. It was a radical change from the attitudes at school, and I found that to be a very thrilling experience.” Being required to read the latest literature as preparation for his tutorials and writing essays meant that Professor Dawkins became extremely well versed in his field, and impressed upon him the importance of argumentation, of coming up with one’s own views on a subject.

His love of a good debate has garnered him a reputation for being combative in his stances. In particular, his firm belief in the truth of science has led him to become a passionate advocate for atheism, a stance which has often landed him in hot water. While touring New Zealand last month, he wrote a column criticising its policy of teaching Māori knowledge systems as part of science. This raised the ire of various New Zealand academics who declared Professor Dawkins’ views as inaccurate and “full of racist tropes”. But Professor Dawkins’ response is characteristically robust. “Science is tried and tested, it’s peer-reviewed, its experiments are repeated in labs all over the world,” he tells CUHK in Focus. “Beliefs that are based on tested evidence, verified evidence, are in a different category from mythology, which is based on tradition.”

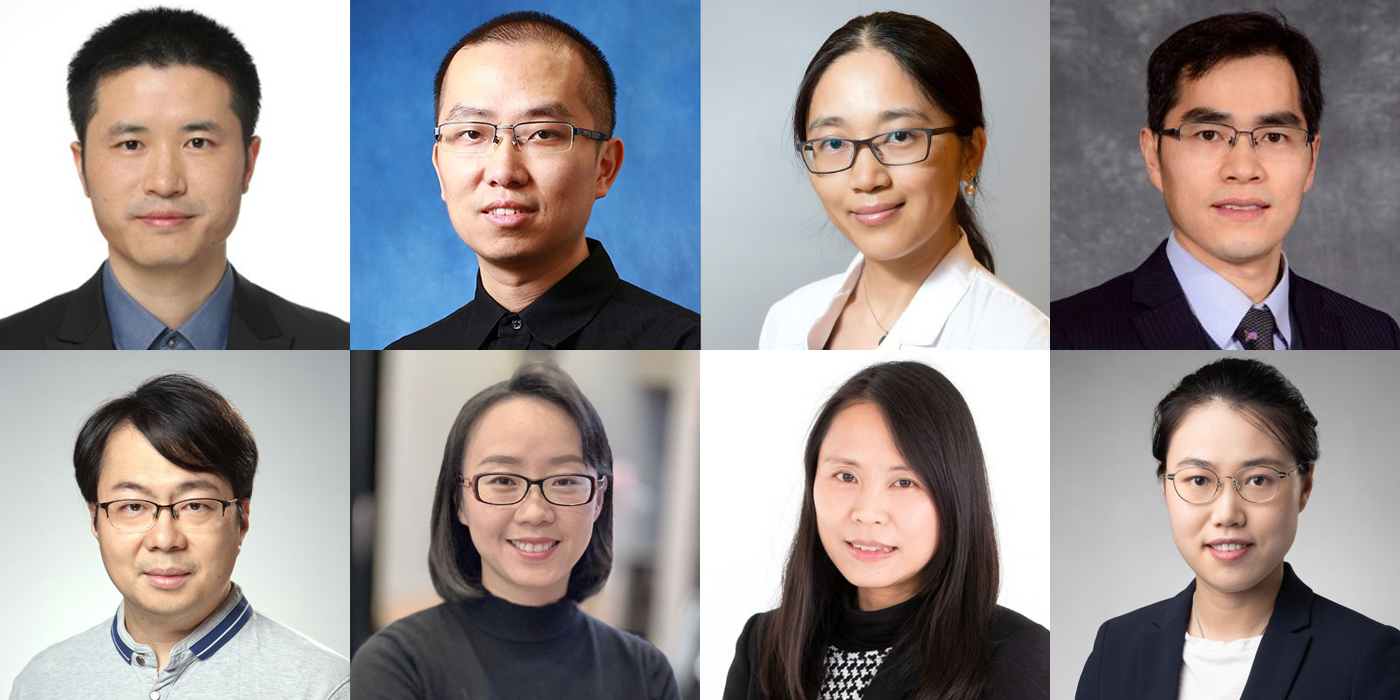

This firm conviction in the absolute credibility of science has led to a series of books and documentaries, in which the professor patiently explains the theories of evolution and associated concepts. At last week’s reading, CUHK Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Master of Morningside College Professor Nick Rawlins, a close friend of Professor Dawkins for some fifty years, suggested that Professor Dawkins may have even founded the genre of “popular science” as we know it. His works, noted Professor Rawlins, “make science accessible without simplifying it” and retain a touch of the poetic even when dealing with vast, complex subjects.

When asked how one can educate the masses without falling into jargon or pandering to the lowest common denominator, Professor Dawkins has this to say: “I wish scientists would think to themselves, even when writing scientific papers for each other, ‘suppose a layperson were reading this, would they understand?’” He cites his own semi-jokey “Law of Obscurantism” in sending up overly complex analogies: “Obscurantism in an academic discipline increases to fill the vacuum of its intrinsic simplicity. My experience is, if you work hard at explaining it to somebody else, you understand it better yourself.”

Although he is already in his early eighties, Professor Dawkins shows no signs of putting his feet up. He says that what continues to drive him on is “a love of truth, a love of education, a love of encouraging people to think for themselves.” His stopover at CUHK in early March, his first visit to Hong Kong and the University, is the epilogue to his lengthy speaking tour of the Antipodes. As one of science’s greatest living educators, he resists answering questions about what advice he would give to those who aspire to follow in his footsteps. But he is merciful enough to offer the following: “think for yourself, believe the evidence, and don’t listen to mythology — find out what’s true.”

By Chamois Chui

Photos by Pony Leung