Professor Tan Yen Joe (second from left) and his PhD students.

Finding fault: CUHK team journeys to East Pacific to probe undersea volcano

When submarine volcano Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai in South Pacific erupted in January last year, it threw a 58-km tall plume into the air – the highest ever recorded in a volcanic blast — causing great casualties and economic loss. The disaster has renewed concerns about the need to improve surveillance of volcanic activity.

“If you look at volcanoes around the world, most of them don’t have any in situ monitoring,” says Tan Yen Joe, Assistant Professor of the Earth and Environmental Sciences Programme at CUHK. “There are no monitoring stations sitting on top of them, so we’re pretty much blind to what’s happening.”

There are well over 1,000 potentially active volcanoes worldwide. Without proper monitoring equipment, scientists can only rely on unsatisfactory data like unusual changes in the terrain and gas emissions to predict an eruption.

“99.9% of them are not well-studied”

Professor Tan continues: “About 70% of volcanic eruptions worldwide take place beneath the sea surface, but 99.9% of them are not well-studied: they’re too far away and it’s very expensive to do so. There’s only a handful that have ever been investigated – you can probably count them on two hands.”

The geophysicist comes from Malaysia, part of a region with numerous volcanoes, particularly in Indonesia and the Philippines, where he says monitoring is patchy. “In places that tourists like to visit, you usually have a couple of seismometers. But in most developing countries, most volcanoes are not monitored at all.”

Where effective monitoring is in place, the results can be dramatic. When Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines blew in 1991, warning signs were spotted as much as 10 weeks in advance, and 80,000 people were evacuated from the area.

“We want to see if we can capture what happens in the year before an eruption and what happens during one, so we can get the complete picture,” says Professor Tan.

Sailing through rough seas

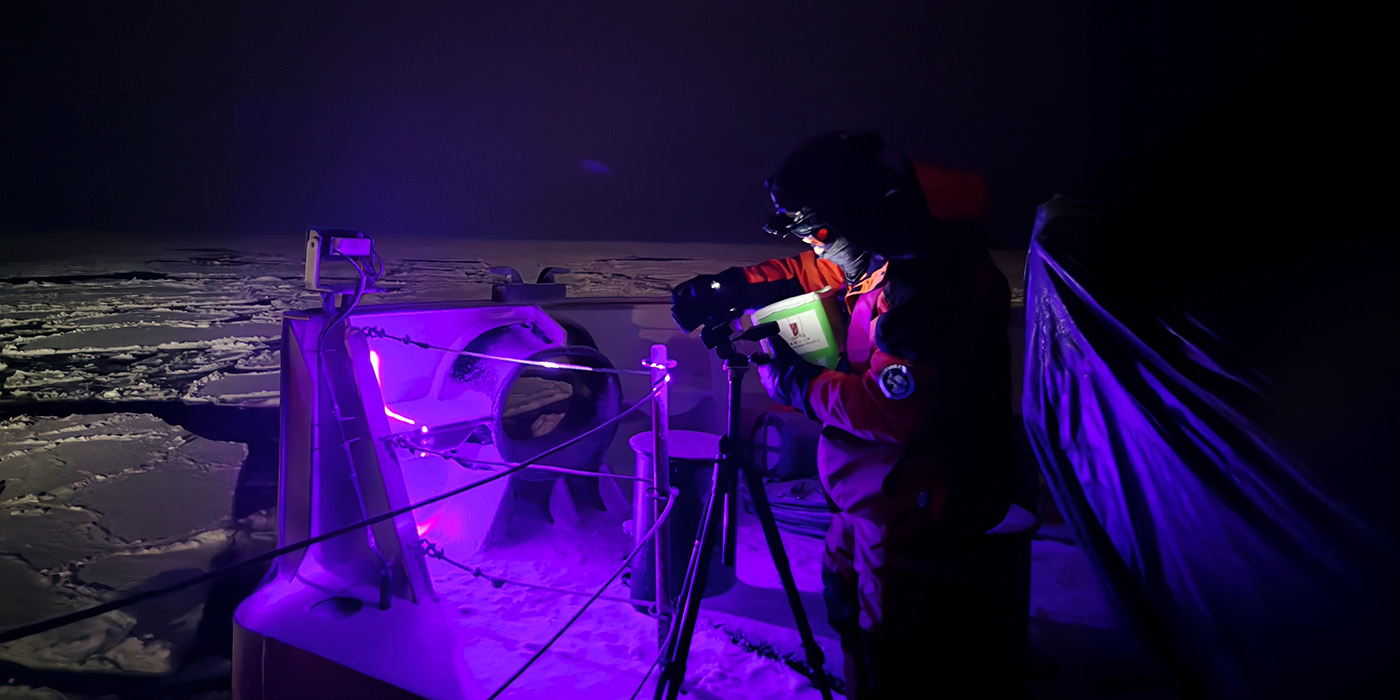

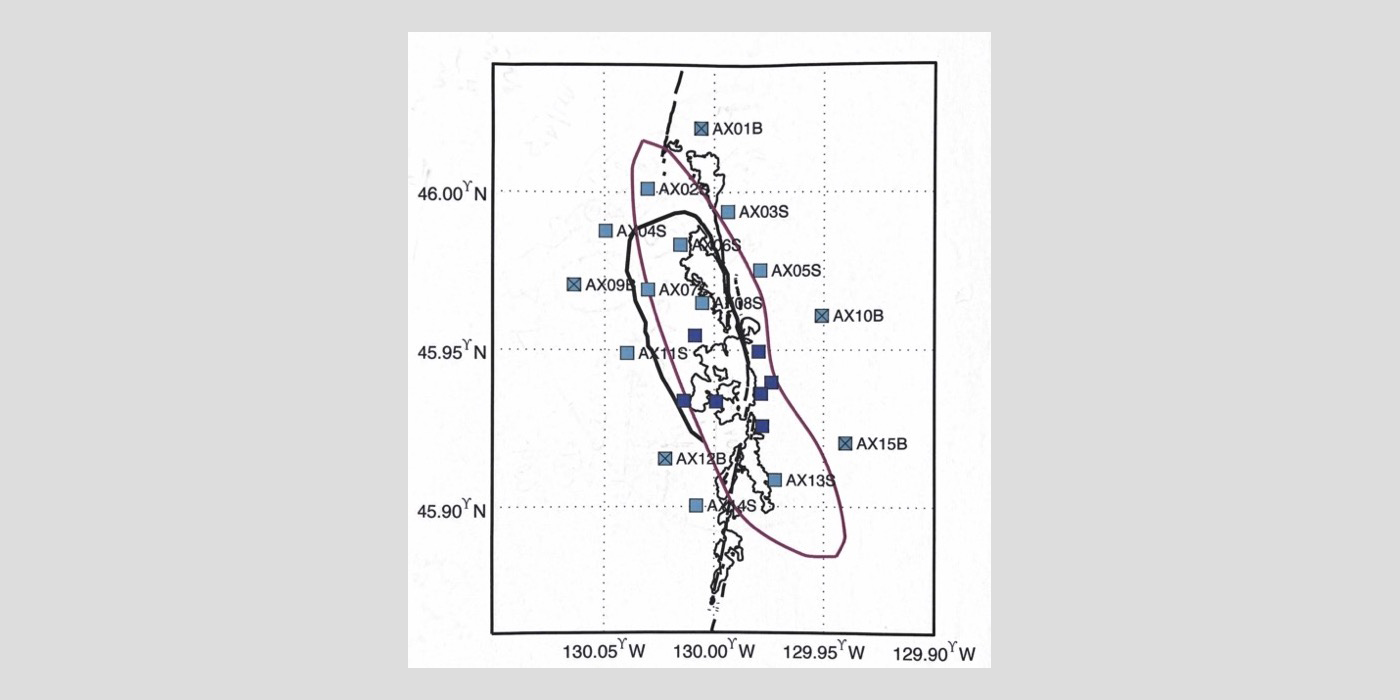

To do that, the professor and his team, including partners from three US universities, travelled in September last year to Axial Seamount, a submarine volcano off the west coast of the US, to deploy 15 ocean-bottom seismometers. Axial, a most active site and relatively more accessible than most undersea volcanoes, is expected to erupt again in the next few years, after doing so in 2015 and 2011, according to Professor Tan. “Each time, it inflates: the ground will swell up as the magma beneath builds up. It’s been swelling up since 2015.”

The journey, featuring a two-and-a-half-day boat trip across choppy seas to reach the volcano, was quite an adventure for everyone who took part. “I brought three of my students with me,” he says. “I asked if any of them got seasick easily, and they all said no. But half a day into the cruise, they all realised that they did.”

At 500km west of Oregon, Axial Seamount is relatively close to the shore of the US where fibreoptic cables are installed to connect an onshore data system with an earlier batch of seismometers installed back in 2015. However, they sit on top of the volcano and can only return data covering a limited area – crucially, not sensitive to activities beneath the magma chamber.

Other seismometers were therefore needed to fill in the gaps although they would not be connected to the onshore data system. The team will be returning this September to collect their equipment and data and to deploy another 15 seismometers that will cover a much larger area.

“You might have small earthquakes or other seismic events that occur below, and [the latest installations] allow you to better track magma movement and how things feed the reservoir as it prepares to erupt,” he says. “The new seismometers to be installed this September will allow us to get a better understanding of what’s happening below the shallow magma chamber – 10, 15, 20 or 30 kilometres below it.”

Professor Tan fell in love with the study of volcanoes when he was studying at Lafayette College in the US. “Since there are a lot of volcanoes in Southeast Asia, I thought I’d study something that contributes to society and how we can do something about it,” he says. He went on to complete his PhD in Geophysics at Columbia University in 2019, and was a Postdoctoral Scholar at Stanford University before joining CUHK in 2020.

He was also the winner of the 2022 Croucher Tak Wah Mak Innovation Award, given by the Croucher Foundation, which provided funding for this project. Further funding allowing, he hopes to install seismometers on more undersea volcanoes – including, if possible, in his seismically active home region.

Reprinted from CUHK in Touch