Journey into life with bioethicists

The human genome was first mapped in 2001, as part of the Human Genome Project, which commenced in 1990. This breakthrough has helped scientists unravel human genetics and develop diagnostics and treatments. However, it was not until 2022 that scientists could fill in the gaps and complete the sequencing of the human genome. “Emerging technologies and relevant policies have been evolving; so is bioethics,” says CUHK bioethicist Professor Roger Chung.

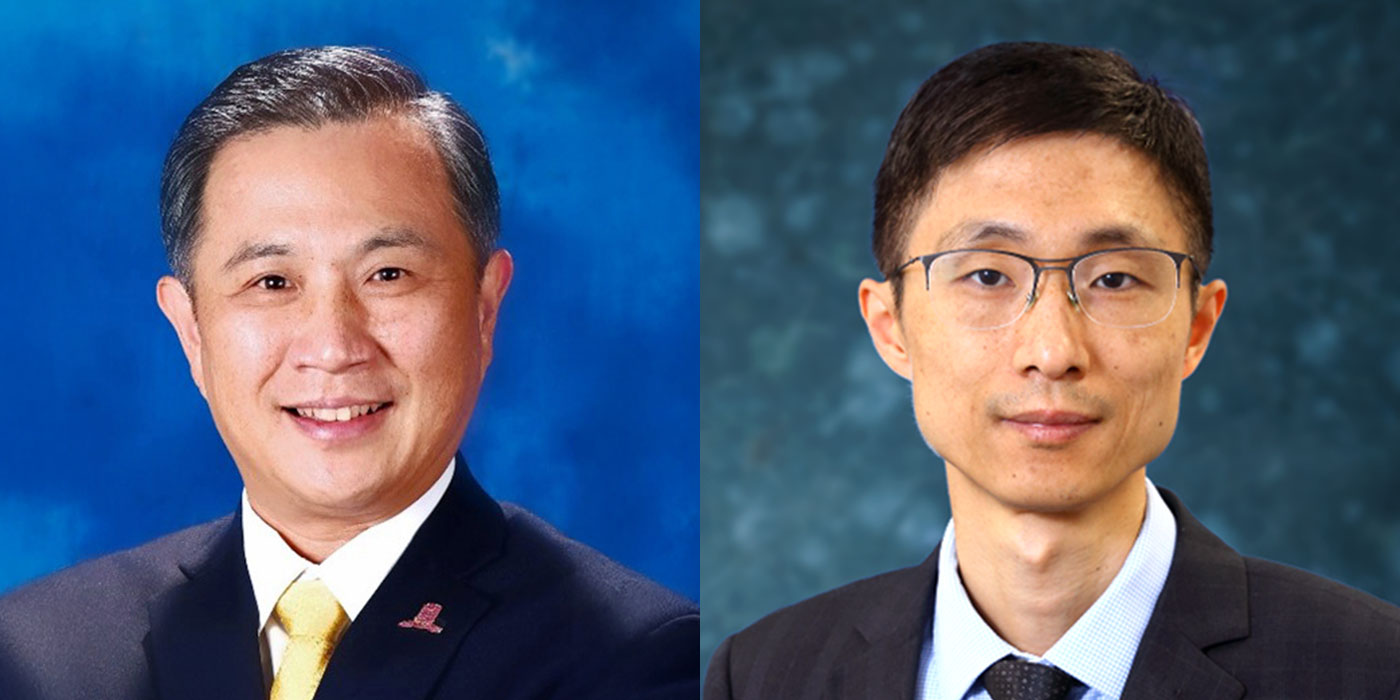

The advancement of biotechnology and artificial intelligence (AI) has presented both opportunities and challenges on ethical, legal and social grounds for educators, researchers, healthcare workers, policymakers and the general public. In early 2015, CUHK’s Faculty of Medicine established Hong Kong’s first interdisciplinary centre for bioethics housed in a leading medical school, with a vision of filling the gaps in bioethics education and research. Professor Roger Chung and Dr Ann Lau have been the co-directors of the Centre since March 2022.

Bioethics has been a feature of the Anglo-European medical curriculum since 1970. The subject started to gain attention in the 1990s in the Asia-Pacific region. At CUHK, medical students are offered training in clinical knowledge, bioethics, communication skills and professionalism throughout the six-year medical curriculum. Faculty members nurture critical thinking on life and ethical values via dialectical methods.

Humanising medical education

Resource limitations and ethical dilemmas are common in healthcare settings. Scenarios include organ donation, resuscitation of a terminally ill loved one, and withdrawing or withholding life-sustaining and standard curative treatments for an end-of-life patient. “It would be too challenging to arrive at spontaneous medical decisions at critical times. Sowing the seeds of bioethics through education and public engagement is crucial,” says Dr Lau.

Young patients tend to be on the priority list for organ donation, but medical judgement goes beyond that. “It’s not just about age. The decision is multifaceted, including the sociocultural, religious, and legal concerns of a specific location. What if the young patient has inborn defects? What if the old patient could contribute to society after organ transplantation? Why is the threshold of organ donation set above 18? All the clinical protocols we observe today are time-honoured wisdom,” she remarks.

The thinking and discussion process matters in bioethics education. “People normally think of a stance before moving on to develop an argument. That’s the other way round in bioethics,” Professor Chung comments. “We need to think about the argument first. For instance, young organ recipients could join the labour force and increase GDP after recovery. However, old patients have contributed to society and could deserve the organ transplant to enjoy their golden age. Developing well-balanced arguments is a prerequisite for coming up with an ethical healthcare policy decision.”

Dr Lau adds that students cultivate critical thinking after ongoing dialectical discussions. “Instead of looking for a model answer or standard protocol, they learn to take different perspectives into account. Biotechnology and healthcare policy are evolving. Students can contribute to perfecting it.”

Reaching a wider audience

The co-directors want to advocate for ongoing discussion and wider awareness of bioethics. To help undergraduates from diverse disciplines understand the interdisciplinary nature of bioethics, the Centre will launch the University General Education course “Bioethical Perspectives on Health, Life and Death” in January 2024. The course will guide students to understand the moral theories and principles in bioethics, identify and discuss ethical issues in selected health-related scenarios, and suggest ways to resolve moral dilemmas in life and death matters.

Discussions on bioethical issues have been extended to community outreach. In March, Dr Lau and her colleagues from the Centre explored the origins of life and abortion with secondary school students. The students examined the definition of life from moral, personal, cultural, religious and legal perspectives, followed by a discussion on the legality of abortion across jurisdictions. In addition, Professor Chung gave a presentation to hospital chaplains on bioethics and equity in May.

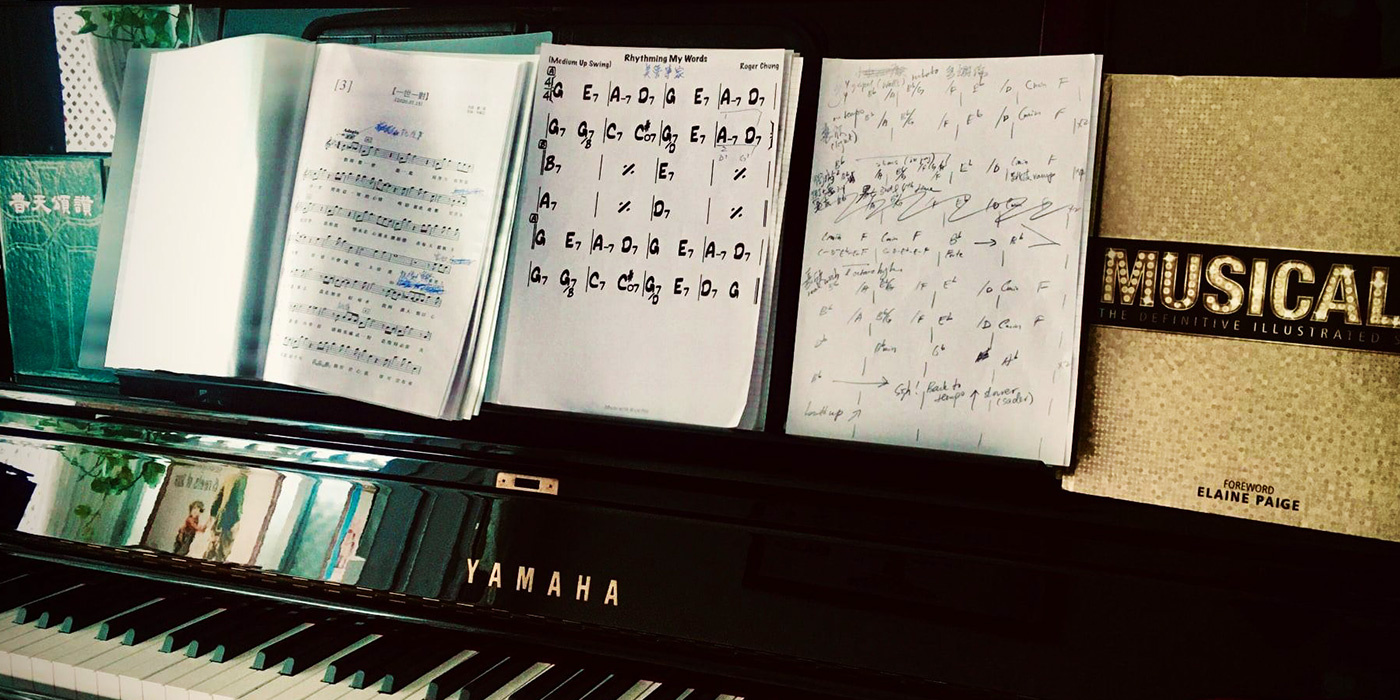

With his passion for life-and-death education, Professor Chung will engage the public by producing a musical drama on end-of-life care and attitudes to death which are culturally taboo in Hong Kong. The musical drama has financial support from the government’s Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship Development Fund.

“Illnesses and death are inevitable. The screenplay, music and lyrics are all based on true stories of end-of-life patients and their family members. It explores themes such as what it means to experience a ‘good finale’ and how to cope with loss and grief. We will also debunk common misconceptions towards death-related matters,” he says.

Forging international ties

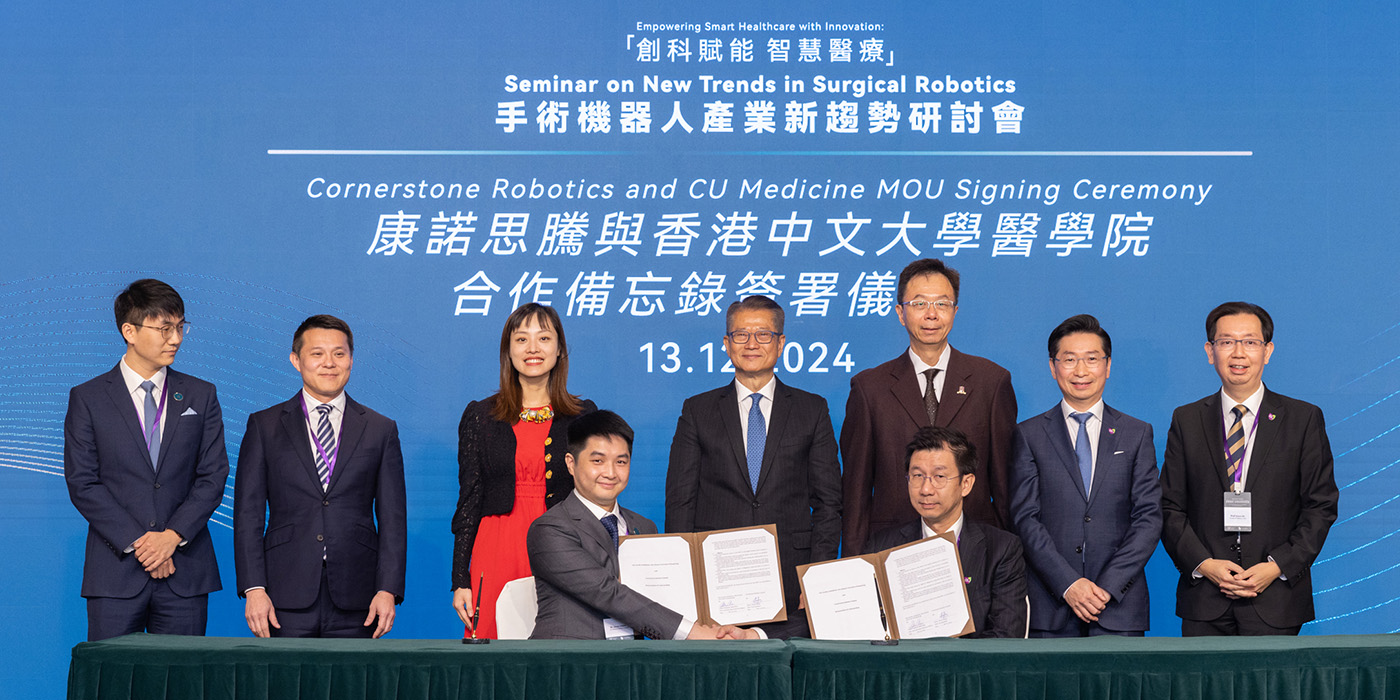

As the nature of bioethics is interdisciplinary, the Centre serves as a hub that gathers scholars, researchers and students working in bioethics from diverse disciplines. In addition to education and public engagement, the Centre will also strive to advance the field through scholarly exchange with its global partners such as The Hastings Center in the US, one the world’s leading institutes for bioethics research.

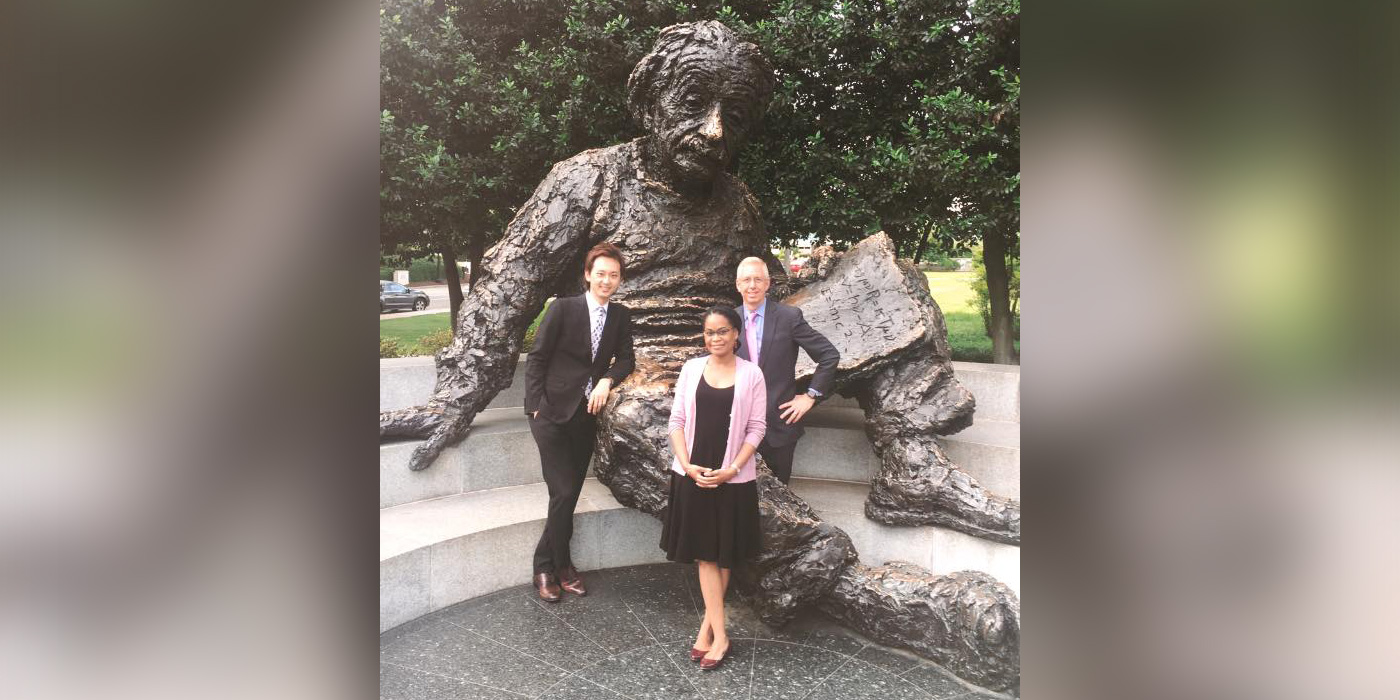

With an aim of training and nurturing global health policy scholars who develop solutions to emerging health challenges, CUHK and the US National Academy of Medicine (NAM) established the International Health Policy Fellowship programme in 2017. As the inaugural NAM scholar, Professor Roger Chung contributed to a study on a global initiative for advancing consensus on pandemic and seasonal influenza vaccine preparedness and response.

AI in healthcare is another burgeoning issue that requires interdisciplinary research. Professor Vincent Chung, the second NAM fellow from CUHK, has been making contributions to the NAM Leadership Consortium’s Artificial Intelligence Code of Conduct project, which aims to synthesise current best practice in implementing AI in healthcare from international literature published from 2018-23 and other relevant guidelines.

The fellowship has recently named Dr Kim Chow as its third scholar, who is working on mechanisms underlying pathological brain ageing and related neurodegenerative disorders. She will be spending 25 percent of her time residing in Washington D.C. focused on scholarly exchange activities and integrating her research into healthcare policies.

In an era of sporadic infectious diseases and rapid advancements in biotechnology, open interdisciplinary dialogue has never been more important. Assuming co-directorship of the Centre in March 2022, when the city was facing its most critical wave of COVID-19, Professor Chung and Dr Lau aspire to inspire future generations with robust ethical thinking via dialogue and an environment conducive to scholarly exchange.

By Jenny Lau