Putting dinosaur flesh back on the bones

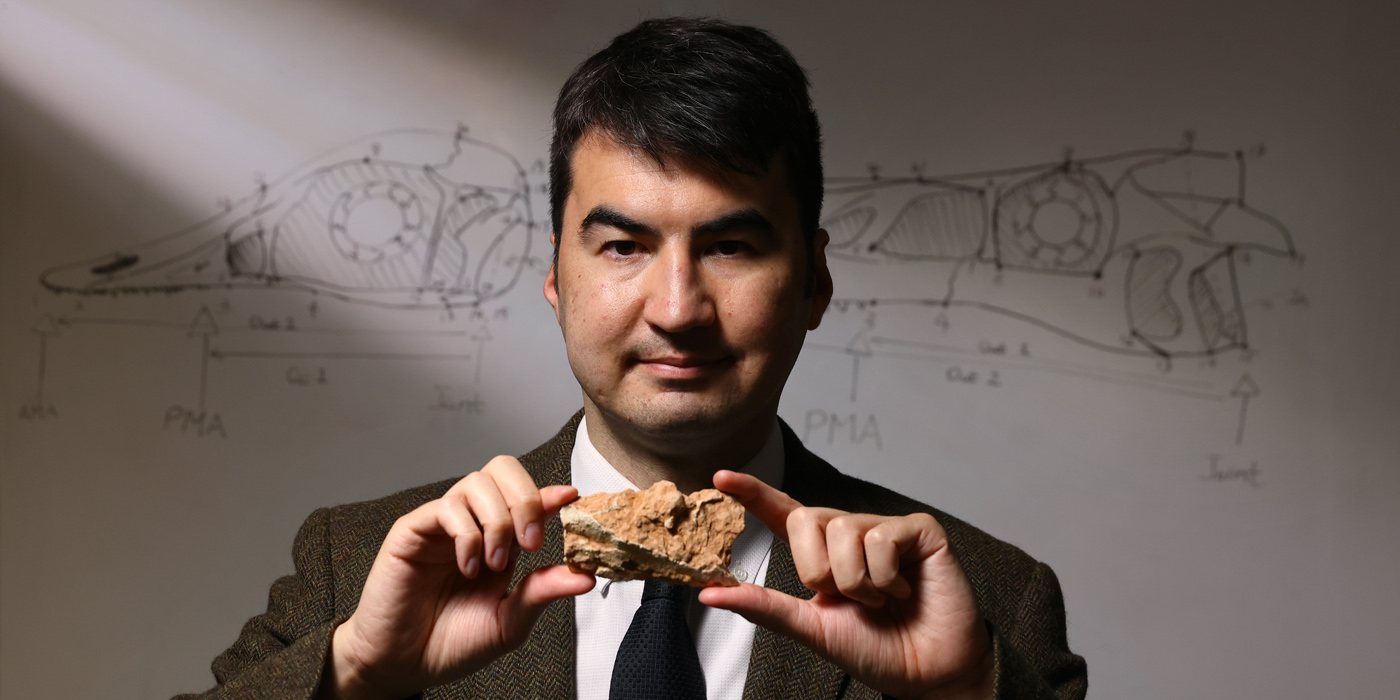

Michael Pittman sheds new light on prehistoric world and beyond

When he was a child, Michael Pittman liked to play with dinosaur toys like any other boys, marvelling at the dazzling features of the creatures that lived tens of millions of years ago.

He would not have imagined that he would carry that interest all the way through to university, where he studied dinosaur tails for his PhD and innovated an imaging technique that has revolutionised people’s understanding of prehistoric life.

“What I am doing today is an extension of an interest in the natural world that I developed at a very young age,” says Pittman, Assistant Professor from the CUHK School of Life Sciences. “Growing up in Hong Kong, I used to go to look at fish at the market and walk around in country parks. That kind of started me getting in biology.”

He has always loved dromaeosaurids, or the “raptor” dinosaurs, which were athletic bird-like predators equipped with razor-sharp claws and curved, serrated teeth. That has driven him to examine the dinosaur-to-bird transition as one of his research focuses.

“Birds are a type of dinosaur. I am interested in how dinosaurs that could only walk and run became ones that were able to fly,” he says. “This is a key evolutionary transition, arguably the most important one since fish walked out of water. My grand challenge is to plug important gaps in our understanding of the dinosaur-to-bird transition that have puzzled scientists for years.”

For 150 years, vertebrate palaeontologists have focused on studying bones. The methods originally available limited understanding of the prehistoric ecology of these creatures. Topic like how dinosaurs moved, their diverse lifestyles, and how some dinosaur species including early birds developed the ability to fly have been filled with speculations and myths.

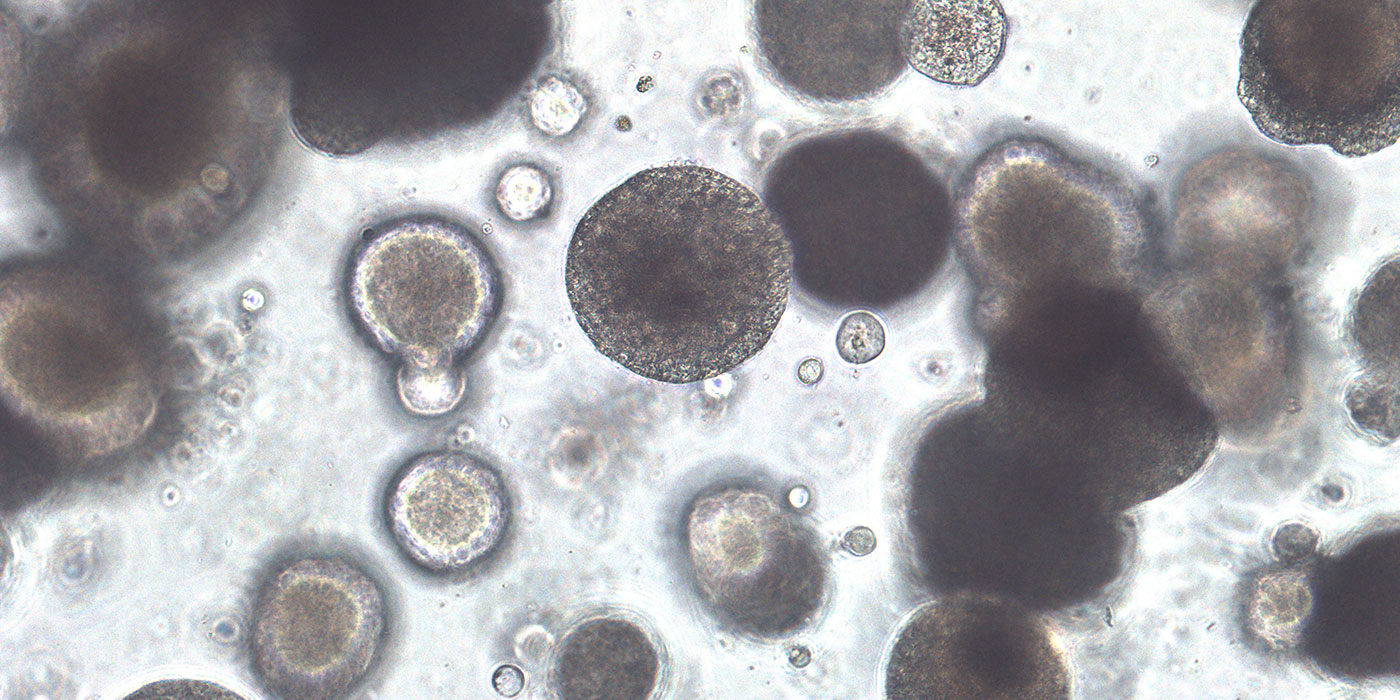

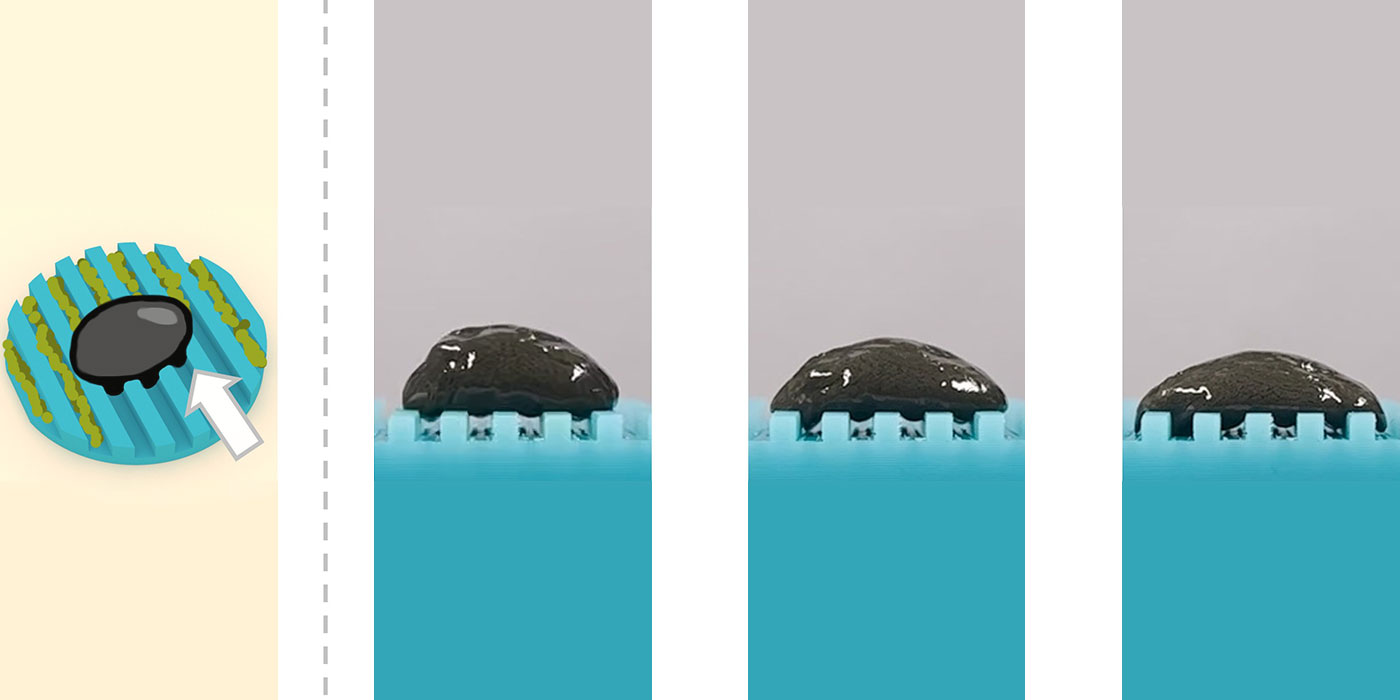

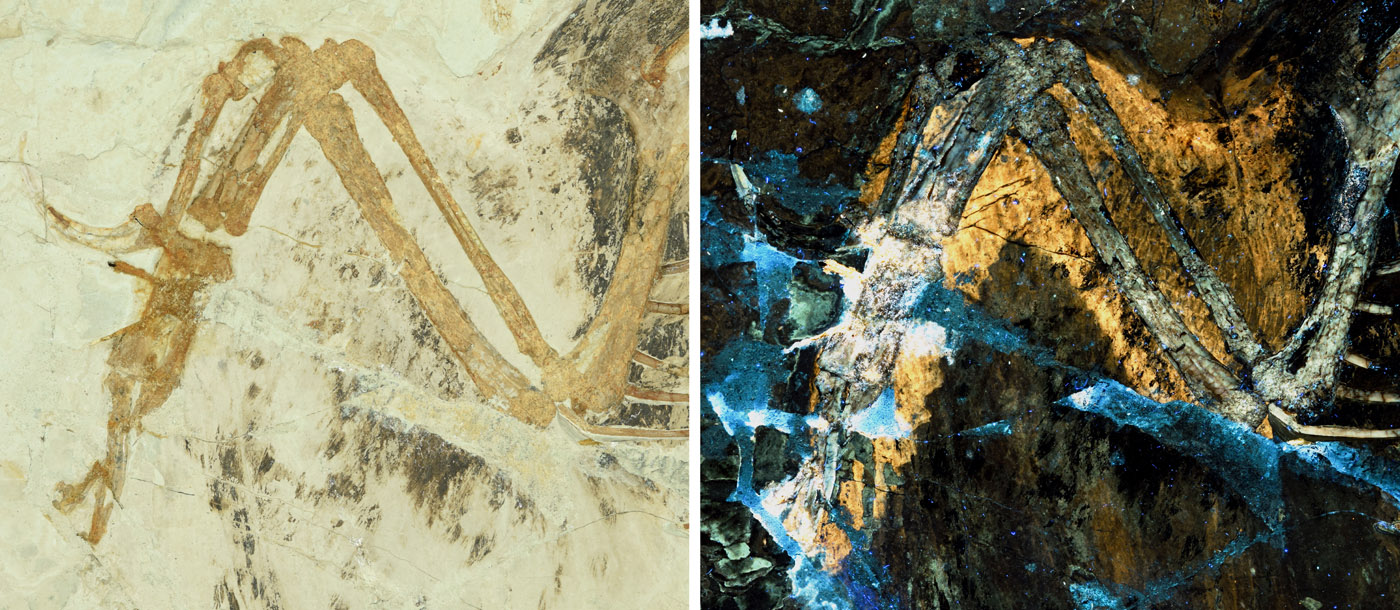

Laser-stimulated fluorescence (LSF) was first introduced by Professor Pittman’s team in 2015. LSF exposes anatomy invisibly preserved in fossils, or as he puts it, “putting dinosaur flesh back on the bones”. It can outline the body and show details of the skin and other soft tissues at levels of detail that were previously impossible using ultraviolet imaging.

The method, which he co-developed with Thomas G Kaye of the Foundation for Scientific Advancement in the United States, can also show differences in the chemical composition of fossils, as the laser beam shining on a specimen interacts differently depending on the minerals that make up a fossil.

The technology has enabled Professor Pittman to generate a range of new insights into flight origins and other issues. In a paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) last year, his team applied LSF to more than 1,000 fossils of early theropod flyers that lived in what is now northeastern China, housed at the Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature. The study revealed elusive soft tissues that were rarely preserved in the fossils of early birds and validated earlier predictions that flying dinosaurs used not just muscles on the chest, but also on the shoulders.

In a subsequent work on the origins of bird flight published in Nature Communications, the team, studying thousands of feathered dinosaurss under LSF, reported beautiful soft tissue anatomy from the feet of several key early flyers, as well as the shape of their claws and bone joints.

“We were surprised to find that the feet of the flying raptor dinosaur Microraptor are ecologically just like a hawk, right at the top of the food chain. Previously, early birds were thought to be superior in the air compared to feathered dinosaurs. Our new evidence suggests this was not always the case, and that flight evolution is more complicated than we thought.”

A large part of Professor Pittman’s research is conducted in the field in the Gobi Desert of China and the Patagonian Desert of Argentina, which he goes to every year to investigate Gondwanan dinosaur ecosystems.

In Patagonia, Professor Pittman is interested in discovering carnivorous dinosaurs and better understanding why these species in the southern hemisphere were significantly different from those in the north. His team is studying a new species of abelisaurid, a type of carnivorous dinosaur, which dominated the southern continents at a time when tyrannosaurs like T. rex were the kings of the north.

In recent years, Professor Pittman has branched out into archaeology, pioneering the use of LSF in studying ancient artefacts. In Belize and Guatemala, he has been using LSF to examine Maya civilisation by imaging pottery, wall paintings, altars, graves and buildings. This has taken him to environments from jungles, volcanoes and highlands to barrier reefs, encountering all sorts of insects and jaguars in the wild and even fighting malaria in hospital.

But these adventures have proved worthwhile. So far, the team has uncovered hidden details in ancient paintings on the walls of houses in the Guatemalan Highlands, which are still being inhabited by modern Maya. “It was rewarding to receive heartfelt appreciation from village elders for giving the community deeper connections with their culture and ancestors,” he says. “I was blessed by a Maya priest, which was a great honour for an outsider.”

Looking ahead, Professor Pittman says his team will continue to develop LSF for more discoveries in fossils. “By innovating further with the imaging technology we already have, we can go further into that rabbit hole. We are putting ourselves in a position where we can tackle grand challenges that are now just science fiction.”

By Joyce Ng

Photos by D Lee