Creating the maximum out of the minimum

From Shanghai to Venice, architecture at CUHK expands its horizons

CUHK’s Shanghai Centre has been in the spotlight since its grand opening in August, with media reports highlighting its potential to open new avenues of communication and collaboration with innovation and technology partners in mainland China. Situated in the city’s modernistic Yangpu District, the Shanghai Centre is the university’s launchpad for scientific and technological collaborations, as well as academic exchange in the region. As CUHK in Focus discovered, this central mission is reflected in the architectural redesign for the Centre.

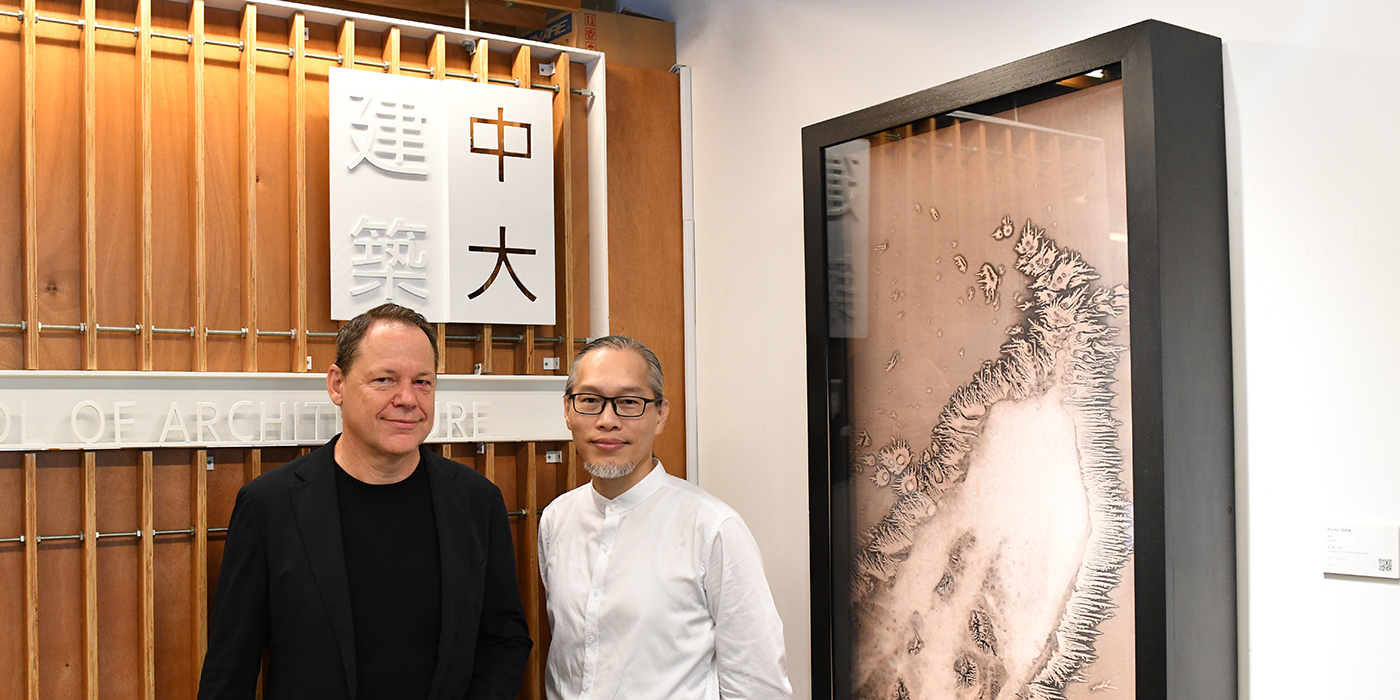

The design was the result of a competition held in collaboration between CUHK and the local district government last December to determine how the premises might be remodelled to fit its new tenants and purpose. Professors Hendrik Tieben, Zhu Jingxiang and Nelson Tam Sin-lung of the CUHK School of Architecture were part of the judging and advisory committee. They reviewed five competition entries in what Professor Tam describes as “a very thoughtful process”.

The winning concept came from designer Zhang Dongguang and his team at Atelier Heimat, a Beijing-based architectural firm specialising in urban space renewal. Although it had a tight deadline (barely seven months elapsed between Atelier Heimat’s win and the opening of the centre), the team still managed to deliver in time. Although CUHK occupies a relatively small section of the building, the competition also entailed the redesign of a much larger area, including the building’s forecourt, car park and atrium. Professor Tieben enthuses about how the redesign binds the disparate design elements together. “Before, it looked very scattered, but now when you come there it looks like the whole place has been rebranded,” he says. “When you come in, it’s very simple and subtle, but these small interventions tie all the elements together.”

The professors are especially impressed with the way people can now access the Centre. Visitors walk through a courtyard shared by the building’s other tenants before being led up a staircase into the space CUHK occupies. “The architect tried to see what one could do not just with this room, but the entire journey,” said Professor Tam. Atelier Heimat ensured that the building served as a response to the locality’s diverse history as entrepot and industrial area. The resulting design, open to use in festivals and exhibitions, helps to “bring people upwards and into the room”. The effect of this smooth flow, says Professor Tam, is that “it links us back to the journey in the development of this very vibrant environment.”

Professor Tieben notes how the redesign, which maximises the uses of minimal spatial resources, reflects the entrepreneurial spirit of CUHK, and goes on to note its resonance with up-and-coming entrepreneurs. “In this regard, it demonstrates the spirit of CUHK — to work with what’s existing and then carve out new opportunities”. Adding to its broad appeal, the professor notes that it has also attracted considerable local interest. “I’m told that many people from the district come and knock on the door, and ask ‘how can our kids study in CUHK?’ People see the entrance, and they want to know.”

Professor Tam, an alumnus of CUHK, concurs on how the architecture of the Centre attests to the University’s spirit. “There’s a lot of information gathered there, a lot of opinions gathered.” He thinks that it has “created the biggest impact to all the stakeholders”, and they have taken the meanings and values of CUHK to heart. “I think from what we can observe now, people are engaged, and even look forward to further phases of this Centre.”

Building future visions

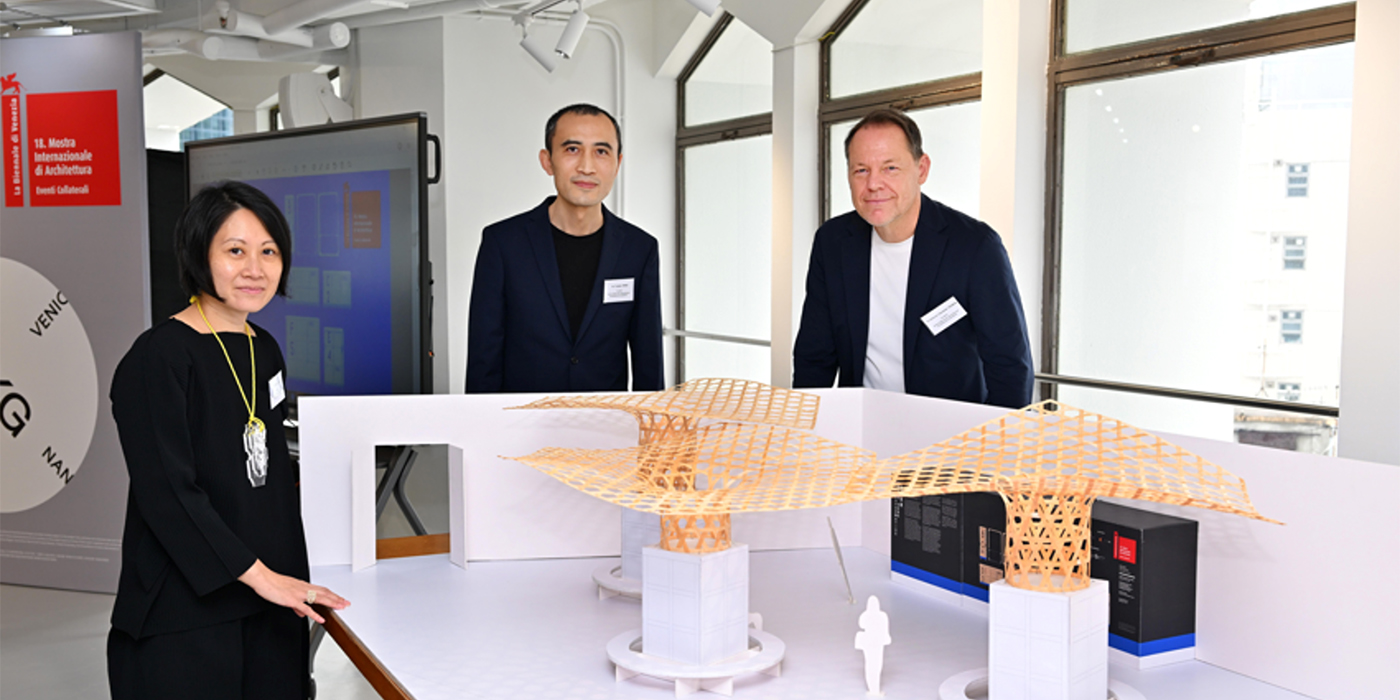

Another recent project from Professor Tieben is his curation of Hong Kong’s exhibition at the Venice Architectural Biennale. One of the most prestigious cultural exhibitions in the world, the Biennale is an arena for artists to present their work and respond to contemporary issues. This year, the Architectural Biennale’s theme was “The Laboratory of the Future”, which encouraged entrants to become agents of change.

Alongside Professor Sarah Lee and Yukata Yano of the Hong Kong Institute of Architects, Professor Tieben helped develop Hong Kong’s exhibit within a tightly compressed timeframe: “Hong Kong prides itself on its speed, and the organisers only started searching for curators in December of 2022, for an exhibition starting in May!” But the curatorial team was able to create a proposal entitled “Transformative Hong Kong”, that showcased the breadth and depth of architectural design in the city, one that could respond to the theme of the Biennale.

The Hong Kong exhibit aims to portray the city’s progression through epochal shifts that profoundly change the cityscape. Professor Tieben gives the development of the Northern Metropolis, a 20-year project to create a brand-new satellite city, as an example. “That is an opportunity, but it also presents challenges, and we wanted to basically show what was happening there on different scales.” Splitting the exhibit into three strata of development — territorial, architectural, and public spaces — the participating architects examined the use of urban space in Hong Kong, as well as solutions to the challenges it posed.

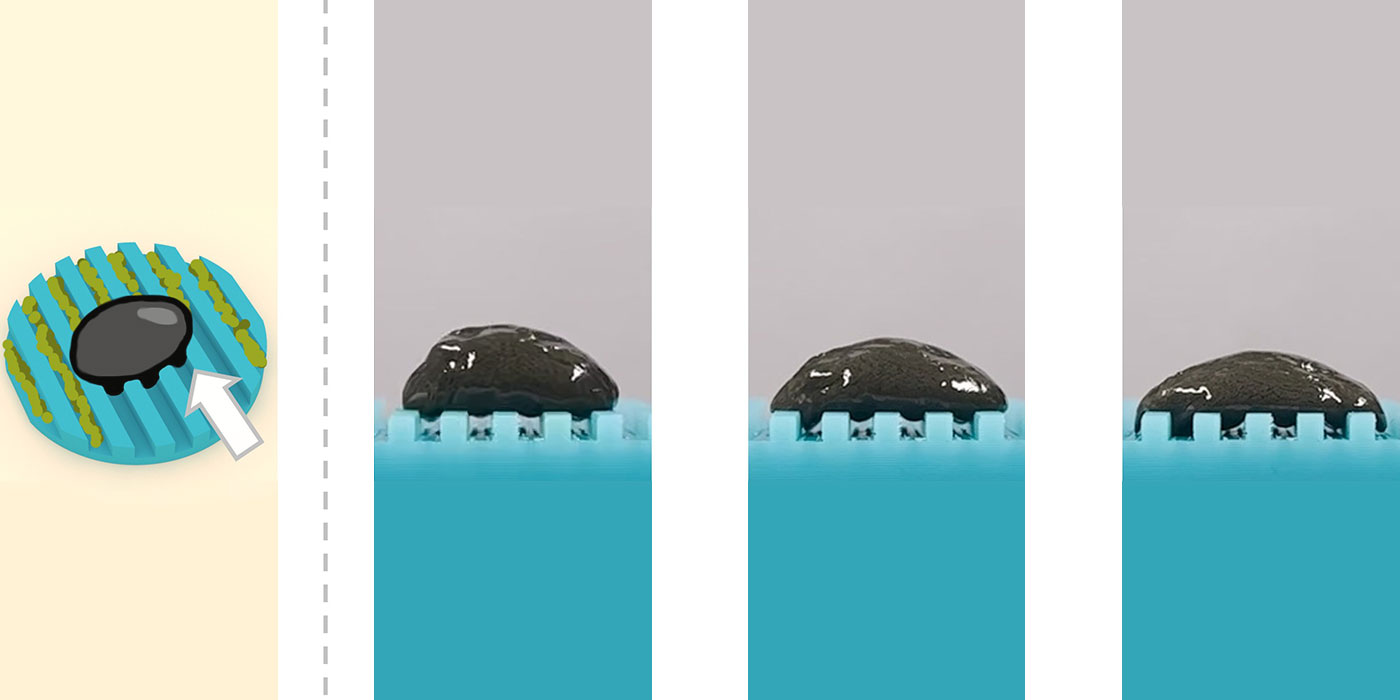

Professor Tieben is full of praise for the ingenuity these architects displayed: “There’s always a question in Hong Kong: ‘how can we do something that is most effective within a very short time and a small budget?’” The exhibition has shown Hongkongers’ resourcefulness in using different resources, such as plastic waste or plants, to create new items such as benches and dioramas. From bamboo pavilions to night market stalls, the professor finds an agility and flexibility in the city’s structures. This itself was replicated in how the Architectural Biennale exhibits were placed into flat-pack boxes that, when unfolded, doubled as exhibition cabinets or panels.

“A lot of people in Hong Kong civil society have different views,” notes Professor Tieben. “But they all have the city at heart somehow. They want to make it better. There’s something positive about this dynamic in Hong Kong, and we’ve tried to capture that in our exhibition.” The Venice Architectural Biennale runs until 26 November, so anyone visiting over autumn can still see the Hong Kong showcase.

by Chamois Chui

photos by Matthew Wu