Our generation’s challenge

Economics is ethics, says chief architect of poverty alleviation in developing countries

In 2005, Professor Jeffrey Sachs wrote in The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time that the wealth of the rich world and the power of today’s vast storehouses of knowledge made the end of poverty a realistic possibility by the year 2025.

Two years ahead of his target date, the eminent macroeconomist at Columbia University agrees that the world has not come close to his vision—but he still sticks to his lifelong pursuit of ending extreme poverty.

At the University’s honorary degree conferment ceremony in early October, where he accepted an honorary doctorate in social science, Professor Sachs said: “I wrote in 2005 that we could reach the end of poverty by 2025. But it was a conditional statement, so I am not going to retract this.”

“Will we have the good judgment to use our wealth wisely, to heal a divided planet and to forge a common bond of humanity and shared purposes across cultures?” he wrote in his 2005 book, which is seen as the landmark exploration of how the world’s poorest citizens can escape from extreme poverty.

Professor Sachs, who has served as an adviser to three secretaries-general of the United Nations, is adamant that the question he posed 18 years ago is still valid today. At the ceremony, the professor recounted how he was inspired by one of the greatest economists in history.

“In the depths of [the Great] Depression, John Maynard Keynes, one of the greats of the 20th century, who invented macroeconomics, wrote an essay titled ’Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren’. It was fully transformative for my life.”

Be hopeful and be kind

The global economy was in dire straits when Keynes penned the essay in 1930. The great British economist “takes wings into the future” and envisaged how economic life would look towards the end of the 20th century, according to Professor Sachs. Keynes’s foresight, which rose above the pessimism of the times, inspired the young Sachs.

“Keynes explained that poverty would be eliminated in England by the time of his grandchildren and he proved to be completely right, notwithstanding another decade of depression, the second world war and loss of empire… it wasn’t magic. It was the logic of continued economic, technological and scientific progress,” Professor Sachs told the audience in the 30-minute, unscripted speech.

In The Economic Consequences of the Peace, based on his experience of taking part in the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, Keynes lamented the allied powers’ harsh treatment of Germany after the first world war. The book shaped Professor Sachs’s lifelong philosophy.

“Everything I advise comes from his basic lesson: be nice,” he said. “Don’t be punitive, don’t cancel other countries. Economics is ethics, and the core of ethics is there are normal people in every place in the world, and the capacity to find a path of cooperation.

“We have the economic and financial means to cooperate and help solve each other’s problems: not to aggravate them, not to create them out of some hegemonic desire.”

A common bond of humanity

Making the world a better place through international cooperation has been the lifelong pursuit of Professor Sachs, who has been an economic adviser to governments around the world. A champion of sustainable development, he was involved in developing the 17 sustainable development goals and is president of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network. In a separate interview with CUHK in Focus and several media outlets ahead of the honorary degree conferment ceremony, he said that humanity was facing bleak prospects.

“Almost no country in the world has a sound climate and energy policy. Norway, Sweden and Denmark have taken quite large steps, but these, albeit advanced, are very small economies. China, the US, Russia and other major economies are going far too slow in energy transformation and in Asia, coal has continued to grow in use in the past 10 years.”

Professor Sachs stressed that a clear strategy is needed to decarbonise the planet: “We need plans of how we would go from today to 2050 to end the fossil fuel era. Countries are only making minimum efforts, hoping someone will bail them out or someone else will do something more. This results in globally inadequate action.” Another problem, he added, was countries proclaiming that they care about the climate but still trying to develop their final fossil fuel reserves. “It does not add up to any kind of progress,” he said.

‘We can’t accept tragedy’

The economist, who is seen by critics as a sympathiser of China, said his viewpoint was ingrained in his belief that cooperation brings out the greatest good.

“Global reality pushes us very hard towards cooperation. We need a global system that functions properly. I start from the proposition that the gains of cooperation are overwhelmingly large and I know, as an economist that has worked on these issues for more than 40 years, how deeply intertwined we are.

“We have a nation-state system where we need global governance. It means our international institutions, including the one I work for, the United Nations, are fragile. It really depends on the cooperation of individual countries, especially the US, Russia and China.

“I do feel my responsibility is to look at my own country first, and criticise my own country first. I hope it inspires others to look at their own countries and to try to improve their countries’ performance.

“I learned to my surprise, in my close contacts with international relations and foreign policy specialists, that they view the world in terms of winners and losers, questioning who is number one: the US or China? I find this question absurd: there is no number one; there is only cooperation and co-existence. There are no winners in a war, only losers. In a world of nation-states, we are still stuck in inter-state conflicts, but we have to move beyond that.”

He recalled his earlier dialogue with John Mearsheimer, a prominent international relations scholar at the University of Chicago, who argued in The Tragedy of Great Power Politics that it was almost inevitable that great powers would end in tragedy, as they were bound to be fighting for dominance.

“My answer to him was: John, we can’t accept tragedy,” Professor Sachs said. “We have to write the solution to tragedy, not to accept it. This is not automatic or easy, and I’m not predicting success. I’m just saying we’d better spend our effort to make success.”

By Amy Li & Gary Cheung

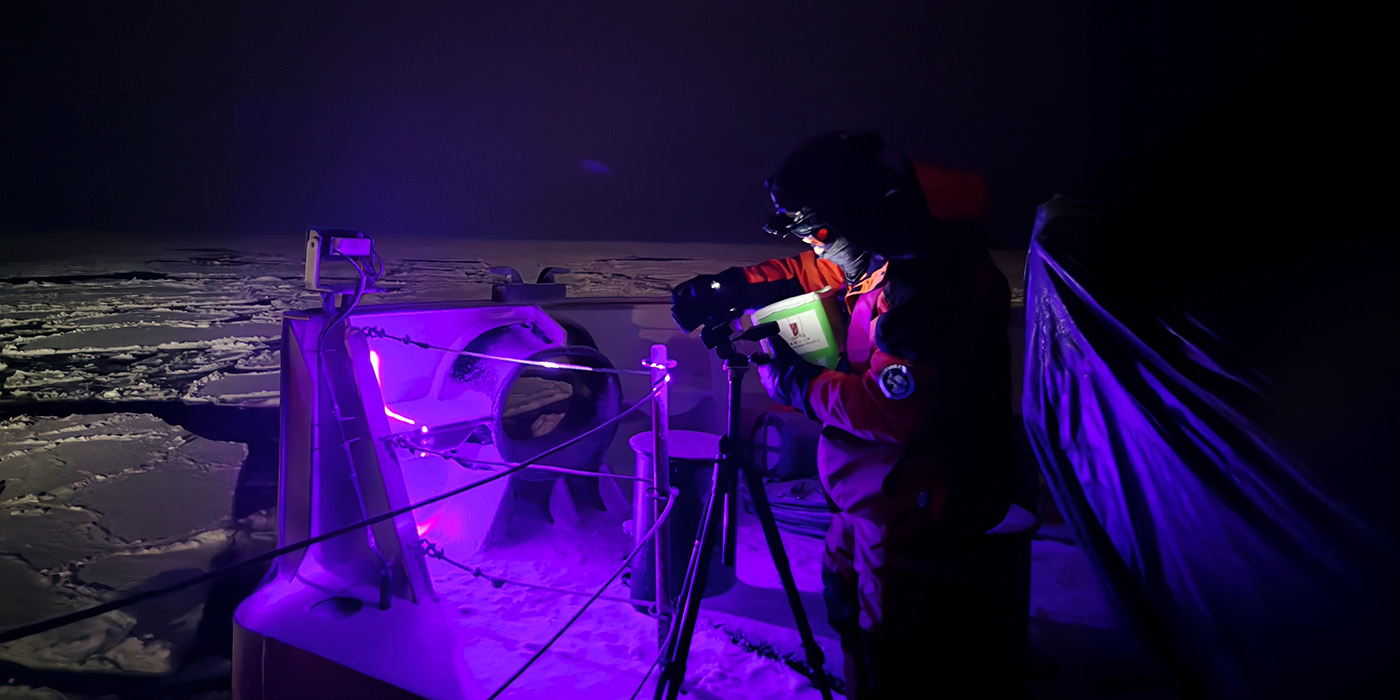

Photos by LCT