Beauty and the Brutalists

Insights into a unique architectural feature of CUHK

Known for its beautiful campus overlooking scenic Tolo Harbour, CUHK is home to a unique cluster of structures, built decades ago in the architectural style of “Brutalism”. Designed by celebrated local architects, campus landmarks such as Science Centre, Chung Chi Hall Student Centre and United College Wu Chung Library are today popular as backdrops for photographs.

Hong Kong architect Bob Pang, lead author of Unknown Brutalism Architecture in Hong Kong, has been leading a team to research and uncover stories behind these and other outstanding examples of Brutalist architecture in Hong Kong. His aim, he tells CUHK in Focus, is to introduce wider audiences to the work of leading local architects.

Typically, Brutalist structures are massive, geometrical and rendered in exposed cement. Bob explains: “Brutalism in architecture emerged during the 1950s in the UK when the country was in dire need of reconstruction during the post-war era. Most structures were built with raw materials that were easily accessible.” In the 1950s, opinions started emerging about modernist structures of an earlier era being cold and distant. UK architects began injecting new elements into the existing style, which lead to the birth of Brutalism.

“The term ‘Brutalism’ may give an impression of rawness and a lack of refinement. In fact, it refers to the idea of ‘As Found’ – to showcase the realness of materials,” says Bob. “Material and structure are two main features of Brutalism. This architectural style features the use of raw materials such as wood, metal, brick and concrete. The structure and space of Brutalist buildings are also distinctly visible.”

“Yet, how people perceive a building material changes with time,” he continues. “The term ‘concrete jungle’ means that people nowadays tend to see a conflicting relationship between concrete and the natural environment. However, it is interesting that the books we read during our research tell us the opposite. In the 1950s, architects saw concrete as a natural material as it is merely a mixture of water, clay and sand.”

Curiosity-driven research

In his book, Bob uncovers the history of 20 local Brutalist structures. “I started Brutalism research out of pure curiosity,” says Bob. “That was 2019, when I’d been working as an architect for over a decade. I thought my life could be more challenging, so I decided to work on something more interesting.”

A campaign launched a couple of years earlier in Germany to catalogue and save Brutalist buildings provided the impetus. The project, called SOS Brutalism, was invited by the Taiwan Jut Art Museum in Taipei City to curate a local exhibition. “My Instagram account was flooded with posts about Brutalist structures from all around the world,” says Bob. “It sparked the idea for my research and a belief that Hong Kong Brutalist structures should be introduced to wider local and global audience.”

In 2020, Bob started to work on the Design Trust grant proposal, and the project was later co-funded by Leigh and Orange Architects. He gradually met like-minded friends on social media platforms and formed a team dedicated to Hong Kong Brutalism research.

“I am impressed by CUHK’s captivating campus. Its bold yet humble architecture have played a pivotal role in showing me the humanitarian ethos of the University. I hope our efforts will contribute to the conservation of CUHK’s campus, igniting sparks of curiosity for the Brutalist gems that reside within our cherished campus,” says Vivian Ting, alumna of CUHK Architecture.

Brutalist architecture on campus

CUHK alone is home to more than 20 Brutalist structures. The research team was surprised by how architectural interpretations differed between Brutalist structures created for individual colleges and those on the main campus.

“Architect Szeto Wai was responsible for the design and planning of Brutalist architecture in United College, New Asia College and on the University Mall (main campus). College structures that combine concrete with white-coloured walls are relatively more colourful, conveying lifelines and vibrancy. On the contrary, structures on the main campus are made of only concrete. Serving as University landmarks, they appear more solemn and stable,” says Bob.

All Brutalist structures in Hong Kong, including those on the CUHK campus, combine aesthetic elements with functionality, such as the need for ample ventilation and light to cope with Hong Kong’s heat and humidity. Bob says: “We can see the presence of brise soleil on the rooftop of Chung Chi Hall Student Centre designed by architect Dennis Lau. They effectively gather sunlight to ensure indoor brightness. All glass doors on the ground floor can be opened to allow air flow.”

Meaningful, interesting research

It has been a long journey and the team, which comprises four CUHK alumni from the School of Architecture, experienced unforgettable moments along the way. “We have been to many rural places that we would not have visited if it weren’t for research purposes. The discovery of Diocesan Youth Retreat Hostel and Chapel, for instance, was particularly challenging. As we did not have its complete address, we could not use Google Maps and could only rely on the schematics drawn in the 1960s. All we had on hand were the terrains and the names of roads nearby. As we ventured into the unknown paths, it felt like we were on an adventure. It was a memorable moment when the structure finally came into view.”

“This research project brings in new insights, allowing me to learn more about the first-generation architecture on the CUHK campus – their simple and humanistic design that blend in with nature. I hope the University can preserve these valuable assets and see them as useful teaching materials,” says alumnus Kevin Mak.

Another CUHK alumna from the team also shares her experience. “During research, we tried to obtain more findings by reading historical journals, conducting interviews and hosting symposium.”

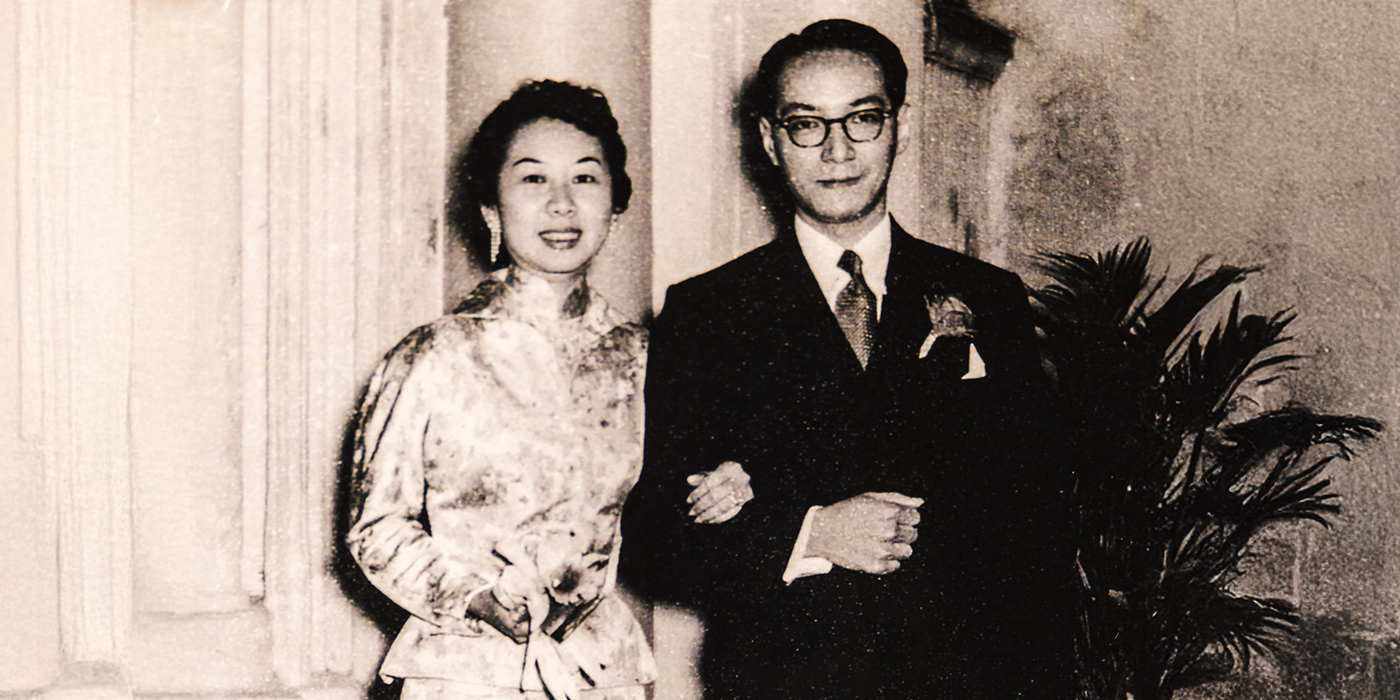

During the research process, even the slightest piece of evidence is valuable. “I can still recall how amazing it was when we discovered schematics in a drawer during our visit to Chinese Methodist Church North Point. They were drawn half a century ago. We were surprised that they were kept intact after so many years,” says Bob. In 2021, the team curated an exhibition in Hong Kong, during which they were privileged to meet different architects and their family members. A face-to-face dialogue with 79-year-old architect Ronald Poon Cho-yiu was particularly meaningful to the team.

“The exhibition includes photography, hand trace drawings, and text records of 15 Hong Kong buildings. We are not simply presenting the original architectural facade, but emphasising the development of the impression we want to express in the creative process,” says Mig Lau from the research team.

“Brutalist architecture is of no doubt a pivotal part of the city’s history,” says Bob. “We believe its value is more than that of the structures themselves. It tells us about an architectural elite that was nurtured and educated in Hong Kong.”

By Gillian Cheng

Photo courtesy of the interviewee and Kevin Mak/1km Studio