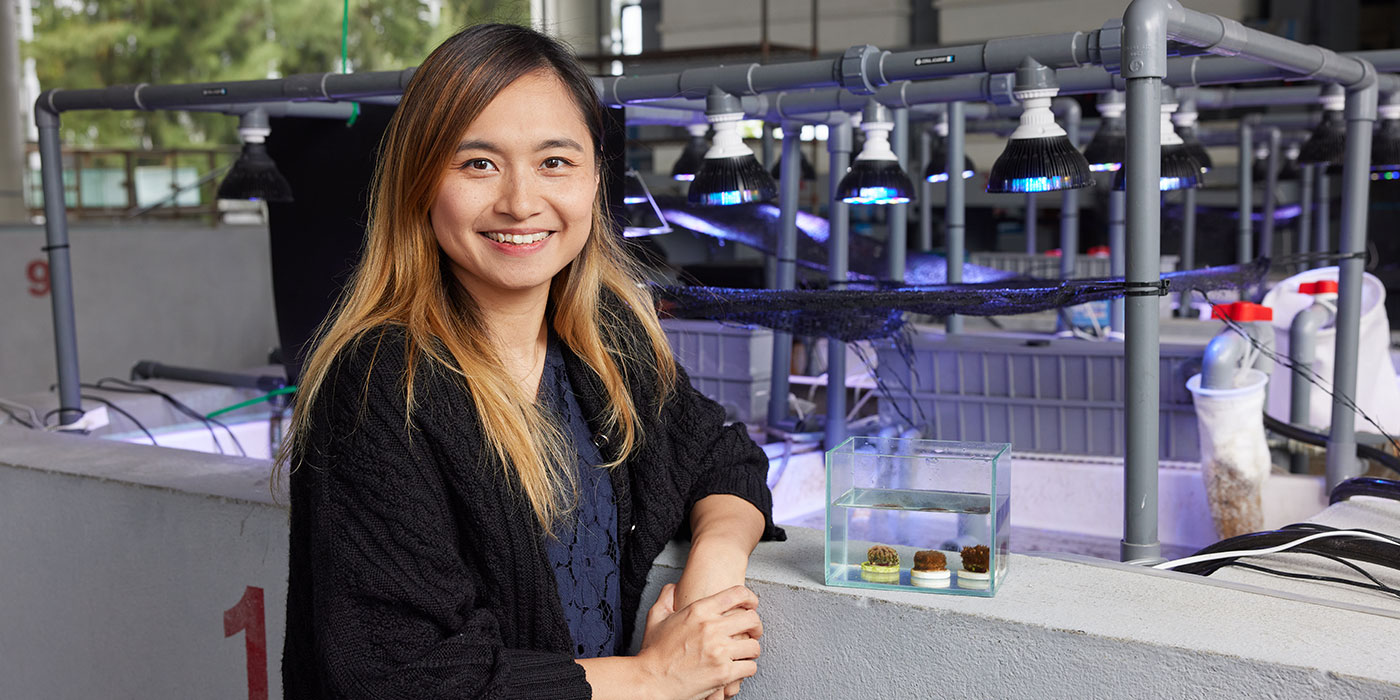

Protector of the sea

Apple Chui nurses corals back to life

Marine biologist Apple Chui knows exactly how to make coral multiply and fill the waters. From a childhood love of the sea, she grew her pet topic through work and study. Now, as research assistant professor of the School of Life Sciences, she has a wealth of knowledge to show by example the science behind reproducing coral.

The spawning of coral is an enchanting spectacle. Professor Chui can talk at length about its early life stages and sexual propagation, but is far from starry-eyed about the challenges of her chosen specialty.

“Coral spawning research is like a fight,” she says. “Corals spawn once a year, which lasts only a few days. If you miss it, or cannot get down to the water due to a typhoon or thunderstorm, the year-long research will have to be put off. You need to be extremely well prepared, as the slightest mistake will cost you the game.”

Rewriting the Tolo Harbour story

Corals are age-old invertebrates that are close relatives of jellyfish and sea anemones. Occupying 0.1% of the ocean floor, they are home to more than a quarter of marine life.

In Hong Kong, corals under the Tolo Harbour and Tolo Channel were headed for a tragic fate owing to the development of Sha Tin and Tai Po new towns in the early 1980s. Water quality deteriorated rapidly, and in the space of six years, the coral coverage had shrunk from 80% to less than 10%. In 1987, the government launched a 10-year action plan to clean up the harbour. But despite a gradual improvement in water quality, the corals did not regrow. Fifteen years after the end of the campaign, coral coverage remained below 2%.

Thus formed the backdrop against which the restoration effort of Professor Chui, then a student, unfolded. It was a no-brainer when Professor Ang Put, her thesis supervisor at CUHK graduate school in 2008, proposed a number of research options. She was studying baby corals and, unable to bear the thought of abandoning them after research, came up with the idea of nursing them and putting them back in the sea. Since then, Professor Chui has been an avid explorer of coral spawning, the enchanting phenomenon once confined to the world of documentaries.

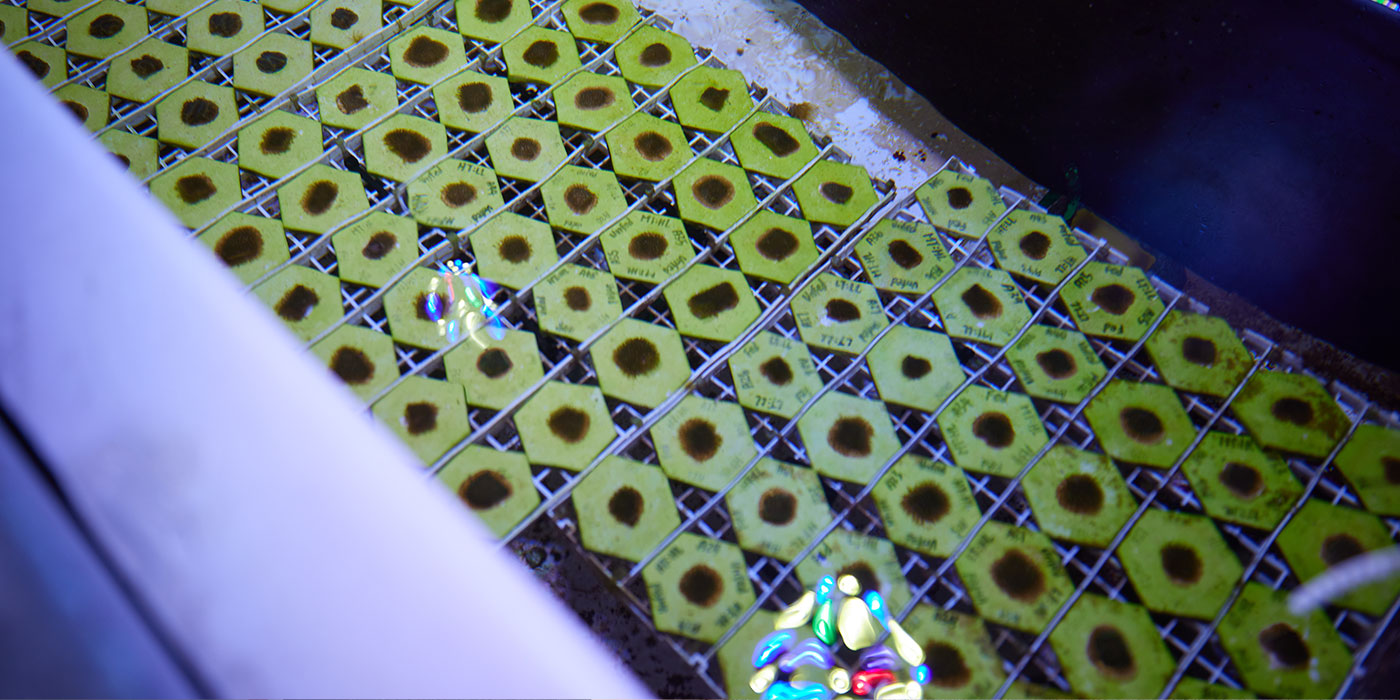

In the laboratory, sexual coral propagation is the process of collecting corals’ egg-sperm bundles as they spawn, then letting the bundles fertilise and grow into larvae, which will stay in nursery tanks for two years before being planted in the sea. Asexual propagation, on the other hand, involves picking up living coral fragments from the seabed. Nurtured back to health, they will self-duplicate and grow.

Professor Chui’s team is the only research and conservation group in Hong Kong that has mastered the sexual propagation technique. In 2019, the team planted 100 sexually begotten, two-year-old acropora corals in the Tolo Harbour and Channel. The good news has not stopped rolling in thereafter: together with 200 asexually produced corals that had been returned to sea, the pilot colony recorded a survival rate of nearly 90%.

A year later, it was found to have attracted indicator species, such as butterfly fish, the latter’s number increasing from one initially to six. “Indicator species indicate the health of corals. They visit only corals that are in good health,” Professor Chui explains.

A year ago, her team observed that five-year-old coral babies were spawning, thus completing a life cycle. They collected the egg bundles and are now cultivating the next generation of coral babies.

Standing ready for restoration

The positive results cannot be cause for complacency, says Professor Chui. “Hong Kong’s corals do not come by easily. We have to protect our existing coral communities. No matter how hard we work and how much good news we have, there is no guarantee of success.

“The key to protecting corals lies in mitigating the effects of extreme weather brought on by climate change. If we don’t reduce our carbon footprint, corals won’t have a future.”

The team’s role, she says, is that of the ultimate rescuer who, on the strength of its successful restoration work in the Tolo Harbour and Channel, may provide seedlings and research-proven techniques once Hong Kong decides to undertake large-scale coral restoration.

“Hong Kong does not have a coral nursery. To grow corals, we need ‘seeds’ and a base. At CUHK, we are setting up such a nursery. Our team is ready in terms of skills and mindset; when the time comes, we may embark on full-fledged restoration.”

Researcher and educator

Research is the source of strong backing to keeping the revived coral scene alive. The microfragmentation technique, for instance, breaks up corals into tiny pieces to make them grow much faster, such that what takes seven years to grow at sea can be achieved in half a year.

“We are unsure of its molecular mechanism yet, though we believe it’s because the corals are devoting all their energies to healing the wounds. Hence, they may achieve exponential growth,” Professor Chui says.

Her laboratory is continuing to study ways of boosting coral growth and enhancing its resilience and genetic diversity. Zooxanthellae, the algae living inside corals that give them the beautiful colours, and other microbial combinations may provide answers to how corals can better resist extreme weather.

Professor Chui has been sharing her knowledge and experience of the sea since she was a master’s student. Now a veteran science educator, she has given more than 100 lectures and won five University teaching awards.

“We are researchers and conservationists sharing our observations on the ground, supported by strong data. What can be more impactful than giving your life testimony?” she says.

In 2018, she founded the Coral Academy, an environmental education and outreach initiative. Its coral nursery education programme, co-hosted by the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department of the government, has been very popular, with 23 primary and secondary schools joining this year to take care of coral babies. The government’s Environment and Conservation Fund, WWF-Hong Kong and Ocean Park are among its longtime partners in restoration, research and education.

Unsurprisingly, the marine biologist has been dubbed “coral mum”, while at home, she is also mother of a three-and-a-half-year-old daughter and has to strike a delicate balancing act between career and family. She does her best and lets God do the rest, she says. “If I’ve done all I can and things don’t pan out, I can accept that—it’s what coral spawning research has taught me.”

By Amy Li

Photos by Keith Hiro