Fantastic beasts

CUHK Art Museum celebrates the Year of the Dragon with special exhibition

Dragons have a legendary status around the world: these monsters, with their fierce yet mysterious natures, have provided cultures with millennia of material for their fantasies. With the Year of the Dragon around the corner, the CUHK Art Museum is presenting an exhibition that explores the way this mythical beast has been depicted in Chinese iconography, and celebrates its role in ancient art.

Dragons have been part of Chinese culture for at least 8,000 years: the exhibition records how the character for dragon, 龍, existed even in the earliest forms of writing. Associate Research Fellow of the Art Museum, Dr Sam Tong Yu, suggests that this shows the importance of dragons even in ancient times – a status borne out by the creature’s frequent presence on contemporary bronze, jade, and stone carvings. He also points out how the conception of the creature has much to do with water and the invocation of rain, which aligns with the river-based nature of early civilisations in China. “Nowadays, of course, we see the dragon as a composite of many creatures: it has some features of snakes, some of crocodiles, all bundled up into this mythical monster.”

Although the concept of the dragon was established very early on in history, early visual representations of dragons were generally quite abstract. However, the Eastern Zhou period saw the emergence of war and trade between China and nomadic tribes to the north, and it was then that images of the dragon become more nuanced and based on observations of actual creatures in the wild. Images of the dragon then coalesced around a few defining features: muscular, two-winged, and more violent in nature. Directing attention to one of the exhibits, a large ornamental belt hook, Dr Tong notes how the intertwisted dragons portrayed tear and bite at themselves, reflecting the naturalistic tendency of the times. The Chinese dragons of that era, he notes, have much in common with the griffins of Ancient Greece, and many scholars have pointed out that this may be the result of cultural exchange between Europe and Asia.

The imagery of dragons continued to develop over subsequent centuries. From the 8th century onwards, contact with the outside world was reduced due to domestic conflict and the rise of other powers along the Silk Road, so inspiration for depictions of dragons turned inward. Characteristic changes including a shorter snout and a broader forehead, and even milder facial expressions, all made the dragon a much more approachable and appealing figure to contemporary viewers. Dr Tong notes that this probably had something to do with the urbanisation of mediaeval Chinese society: “The rise of an urban class meant that when drawing animals, people would tend to emphasise their playful, pet-like aspects, making the dragon more domesticated and comical, and a symbol with auspicious meanings.”

In the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), the use of dragon motifs was legally restricted to the monarch and his immediate family, however, the actual enforcement demonstrated flexibility. Dr Tong notes craftsmen were able to get around this by ingeniously modifying subtle features and obfuscating the creature depicted – “changing the horns of the dragon to resemble [those of] a cow, for instance; or reducing to the number of claws on the animal… still retaining the overall image of the dragon.” A brush holder made by master porcelain artist Tang Ying for his own use is a good example of this ingenuity: the dragon depicted soars amidst clouds, but as the beast only has three claws, it was not considered as a challenge to the sovereignty of the emperors, which was symbolised by the five-clawed dragon.

Made by Tang Ying (1683-1756)

Gift of Mr. Jen-mou H. C. Hu

Acc. No.: 1987.0026

Tang Ying was the official in charge of the imperial kiln at Jingdezhen, a town in Jiangxi province well-known for the immaculate quality of its wares. Although Jingdezhen was a centre of production starting in the Tang dynasty, the Art Museum spotlights its dragon-themed porcelain made during the reign of the Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong emperors as being particularly indicative in representing royal taste during the Qing dynasty’s golden age. “This was an era of heightened popular influence: the dragons of the Kangxi years, with their round snouts and broad foreheads, bears some resemblance to a human face; and with its twisted body and outstretched limbs, they look more powerful and vivacious. This was an innovation that differed from the previous dynasty’s designs,” says Dr Tong. The progression of porcelain production during the Qing dynasty is encapsulated in a set of yellow imperial discs, all made at Jingdezhen and all featuring the dragon. Almost every Qing emperor is represented in this set, with an example of note being a pair with the mark of a private studio, ordered by another imperial kiln director during the reign of the Tongzhi Emperor. Such a brazen law-breaking act, Dr Tong suggests, might indicate the decline of centralised power in the later Qing.

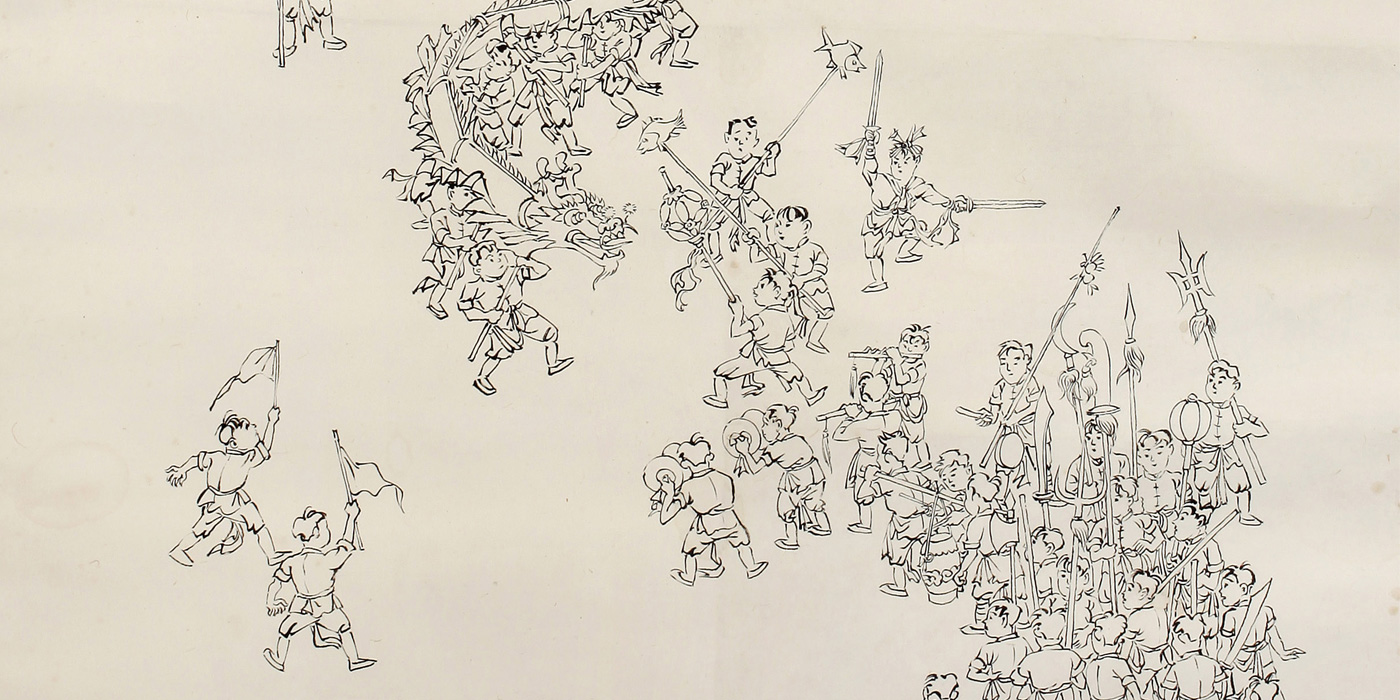

The shifts in dragon iconography reveal a great deal about Chinese culture, from its interaction with foreign cultures to the shifting tastes of people over time and even the way China was governed. As Dr Tong suggests, “From the minute changes in dragon design, one can trace the rise and decline of monarchic power, and from that one can see how society itself developed.” He points to a large sketch, drawn by local artist Yip Yan-chuen after 1949, depicting the celebration of Chinese New Year with a dragon dance. “What it reflects,” he says, “is the staying power of the dragon, long into our modern era.”

A Hundred Children Welcoming Spring, detail

Hanging scroll, ink on paper

160 x 81.5 cm

Collection of Art Museum, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Gift of the Yip Family

Acc. No.: 2008.0448

The CUHK Art Museum exhibition “Celebrating the Year of the Dragon” runs until 31 July, and is open to the public free of charge.

by Chamois Chui