Making strides in green living

CUHK students from Sha Tin and Shenzhen learn about sustainable urban planning

In late May, CUHK’s Sha Tin and Shenzhen campuses held a joint cross-border tour to show students how Hong Kong and Shenzhen put sustainable development into practice.

The 15 participating students went round a number of sites during the four-day Green Camp that started on 28 May. Their tour leaders were Professor Stephen Wong Heung-sang, head of United College, and Professor Lu Zongli, master of Ling College of CUHK-Shenzhen.

Visits to transitional housing projects were among the highlights, given the Hong Kong government’s efforts to ease the plight of tenants living in subdivided flats. The city targets providing by 2026 more than 20,000 transitional flats, of which 14,000 have been completed.

To see how the authorities catered to the socially vulnerable using idle resources and advanced technologies, the participants visited two blocks run by local charity Lok Sin Tong. One was an overhaul of vacant school premises on Cheung Shan Estate in Tsuen Wan, while the other was being built with a modular method on Choi Hing Road in Ngau Tau Kok.

At the Choi Hing Road site, Under Secretary for Housing Victor Tai underlined the government’s focus that human welfare was what it cared about most. Mr Tai, who was on hand to introduce the transitional housing to the tour group, said that based on a study by Lok Sin Tong and the University of Hong Kong released this March, family relations, physical and mental health, children’s psychological well-being and even family incomes received significant boosts after people moved from partitioned cubicles to the new homes.

“Back in those days when they lived in subdivided flats, the children never smiled; now, joy and happiness is written all over their faces—it’s a huge world of difference,” he said.

Innovating for decent homes

The revamped block on Cheung Shan Estate was once Tsuen Wan Lutheran School, which closed in 2010 and was then left vacant for more than a decade. It was transformed by the Housing Bureau on a budget of $40 million into temporary residences, providing 145 flats for families of three or four that had been in the public housing queue for years.

The conversion was accomplished by halving a classroom to yield two flats of more than 200 square feet, each with its own open kitchen and toilet. Solar panels had been installed on the rooftop, which would save up to $3,000 in electricity charges a month. The savings would be channelled to the residential block’s public electricity account.

All in all, construction of the Cheung Shan Estate temporary homes took just five months from October 2021 to April 2022. Compared with the seven years needed to build traditional public housing, it was a quantum leap in time.

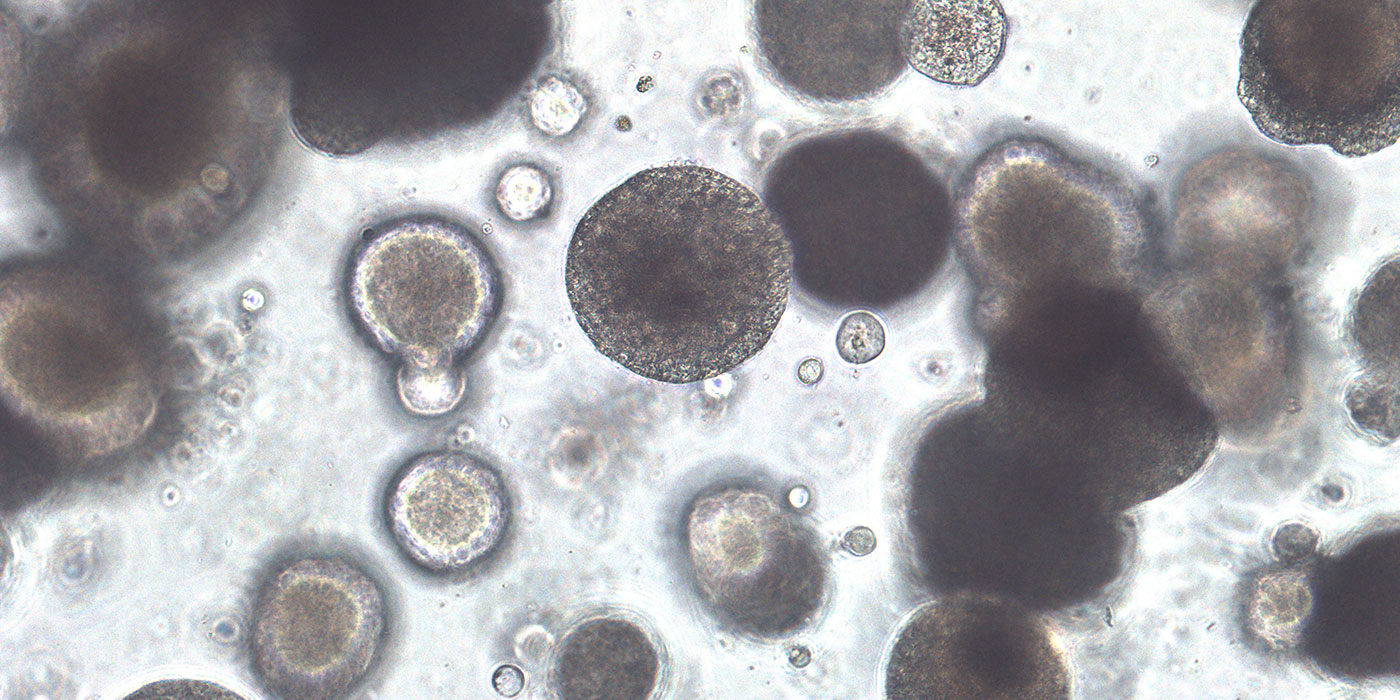

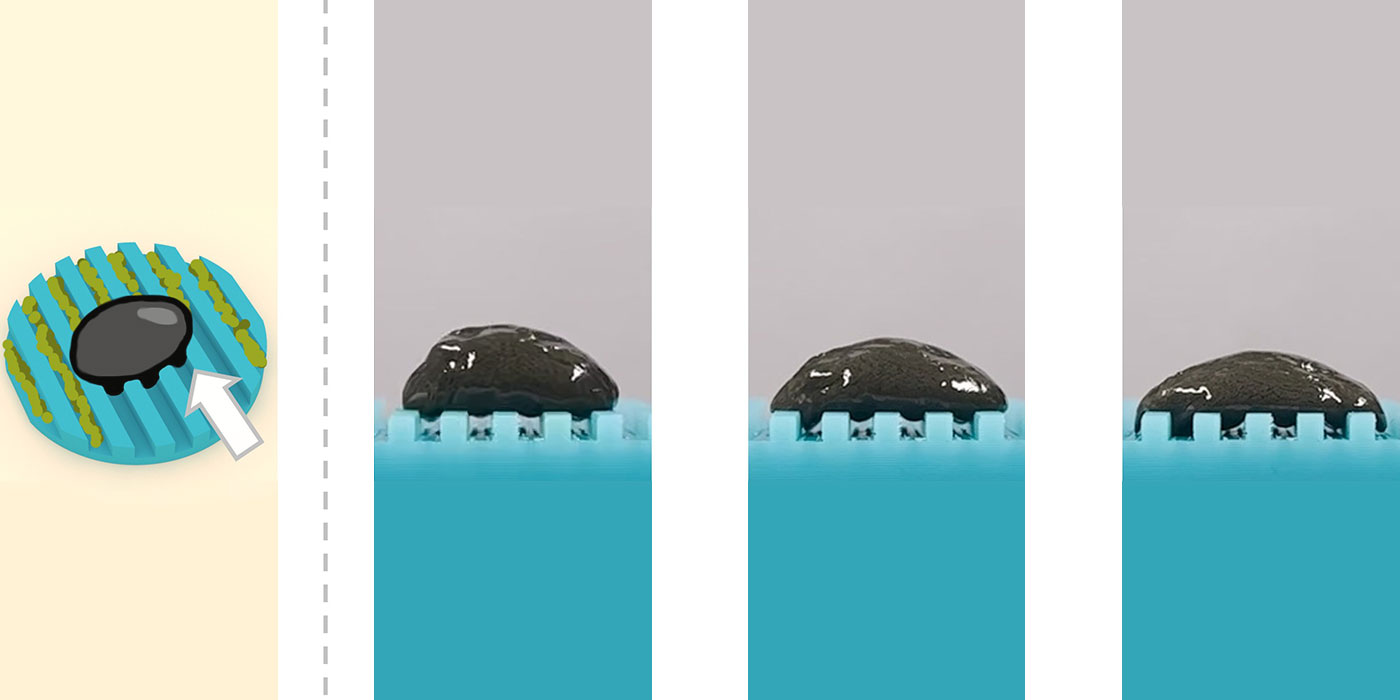

Over in Ngau Tau Kok, the new 329-flat tower took 11 months to complete using a nascent modular integrated construction technique. Each unit was pre-made like Lego blocks in a mainland Chinese factory and installed at the project site.

Yuen Kwok-cheung, the project consultant, said its design was informed by the concept of “passive architecture”.

“We found that some African villages, primitive as they were, had exceptional lighting and ventilation which would put even architect-designed houses to shame. We are infusing green elements into the flats themselves, which dispenses with the need for building and spending on green facilities.”

An insightful itinerary

Green camp participants were left impressed by Hong Kong’s transitional housing initiative. Woody Wu, a sophomore of quantitative finance from Ling College, said: “Before, I’d never seen or thought idle resources can work such wonders, or that the conversion or building costs can be so low. It gives me a new perspective from which to view spare resources, and also to understand the merits of revitalisation.”

Wu said that on the mainland, scores of “rotten-tail buildings” had been lying in decay for years.

Comparing the two cities, he felt Hongkongers demonstrated more environmental awareness in general and put much heart into wildlife conservation. Shenzhen, on the other hand, was ever evolving to align its town planning with modern sustainability trends. It had greater latitude in utilising state-of-the-art technology to process household waste.

Alisa Shen, a first-year student of computer science at Ling College, also regarded transitional housing as an effective means of relieving pressure on grassroots families while putting idle resources to good use at remarkably low costs. The modular construction adopted to build these temporary homes was striking, she said.

Margaret Ren, a fourth-year student of geography and resource management at United College, saw Hong Kong and Shenzhen as different cities with different things to work on. She took particular notice of the Shenzhen East Power Station, a waste-to-energy plant on their itinerary that treated 5,000 tonnes of garbage a day. It was a “smart” facility that Hong Kong could consider setting up, she said.

“In Hong Kong, rubbish is dumped in landfills. There have long been complaints about the foul smell emitting from the landfill in northeastern New Territories. As demand for electricity is high in the city, I hope Hong Kong and Shenzhen can join hands in turning waste into energy.”

Ren’s remarks aptly mirrored the purpose of the Green Camp, the first joint initiative by United College of CUHK and Ling College of CUHK-Shenzhen. Over four days, students from both colleges got out of campus and explored low-carbon architecture, sustainability, renewable energy and wildlife conservation in Hong Kong and Shenzhen. The innovations left a deep impression on participants and could foster their continued interest in the sustainable development of both cities. On the part of the organisers, CUHK and CUHK-Shenzhen have wrapped up yet another event that shows they take their social responsibilities seriously and are committed to upholding sustainability principles in their teaching, research and daily operations.

By Amy Li

Photos courtesy of United College