Into the unknown

CUHK professors chosen as members of national polar expedition

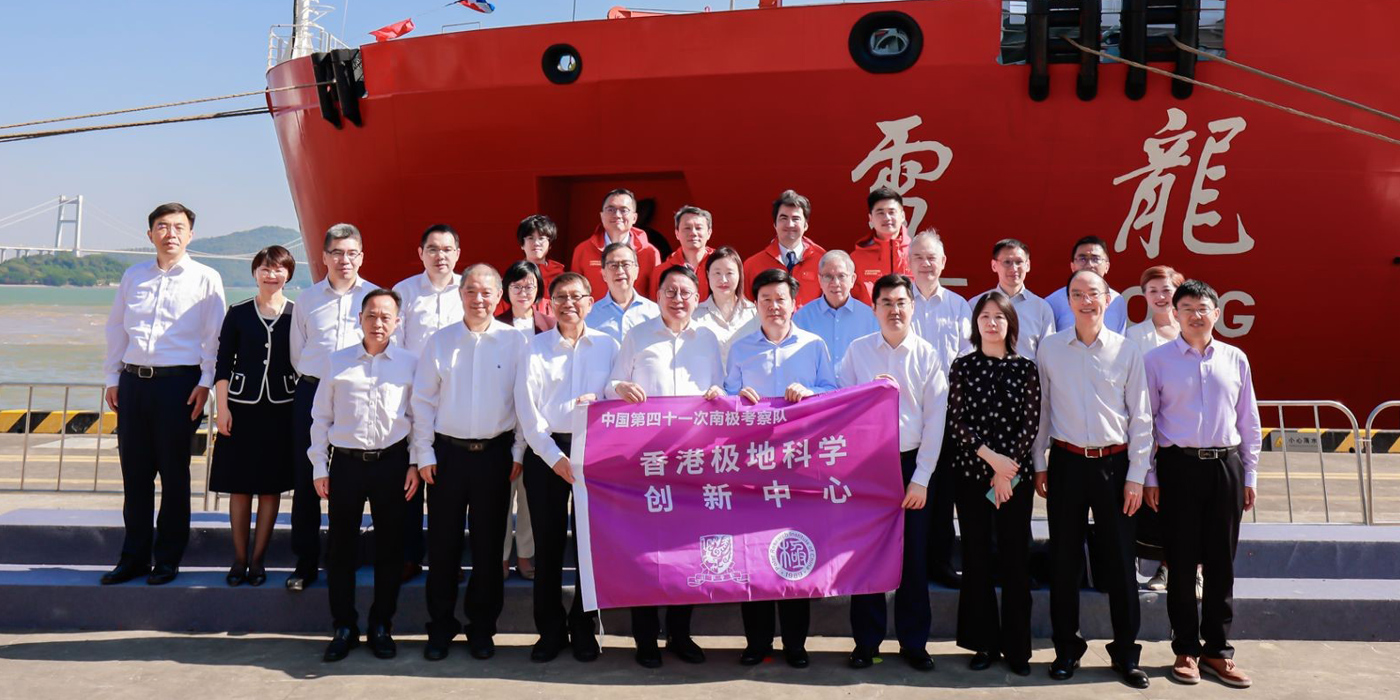

As the cool November wind blew through the docks at the Nansha International Cruise Home Port in Guangzhou, three CUHK scientists participating in China’s 41st Antarctic expedition stood silently in the shadow of China’s first domestically built polar exploration vessel, the Xue Long 2. They watched as dignitaries, including Vice Minister of Natural Resources Sun Shuxian and the Hong Kong government’s Chief Secretary for Administration Chan Kwok-ki, spoke of the importance of their upcoming voyage.

Finally, it was time for departure. A line of people, among them Mayor of the Guangzhou Municipal Government Sun Zhiyang, gathered to see the ship begin its journey south towards the frozen desert of Antarctica. While the people on board the huge polar vessel waved to the crowds far below, the Xue Long 2, along with its sister ship the Xue Long, slowly manoeuvred their way out of the dock, and sailed steadily out to sea.

Seeing new worlds up close

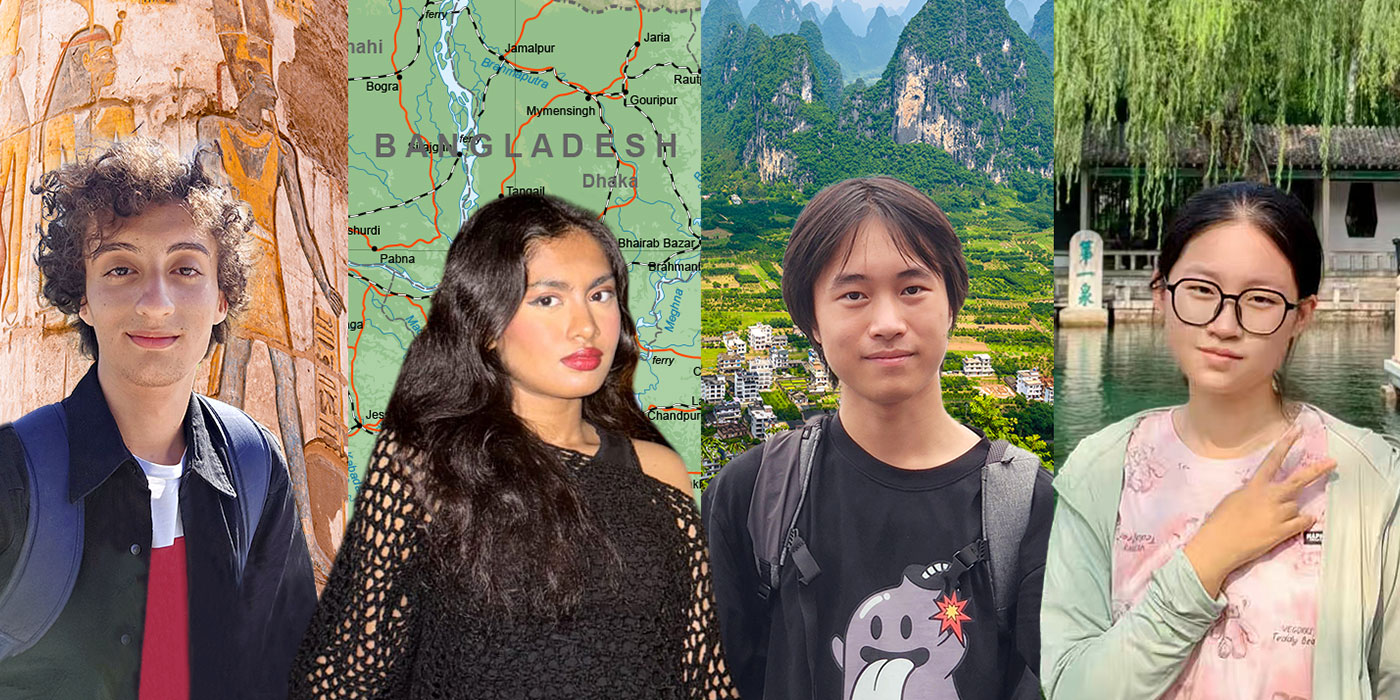

A few days before the ceremony, the three professors who would stand on that dockside in Guangzhou, and leave for the Antarctic in December, gathered in CUHK’s Museum of Climate Change to share their thoughts on their impending trip. Thanks to the Framework Agreement for Strategic Cooperation, signed in August between the University and the Polar Research Institute of China, scientists from Hong Kong were invited to participate in China’s 41st Antarctic Expedition, in a bid to foster collaboration between Hong Kong and the mainland, and these three were among the first batch of Hong Kong scientists invited to take part in a polar expedition.

CUHK in Focus caught up with them amid their preparations for the upcoming trip. They are Professor Alex Chow Tat-shing, Chairman of the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences; and Professors Michael Pittman and Martin Tsui Tsz-ki, both of the School of Life Sciences; they will be joined in Antarctica by Professor Liu Lin of the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, and two other academics from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

An academic devoted to the study of water and soil in the ecosystem, Professor Chow has long been concerned by the effect of climate change on the carbon cycle. “The permafrost contains a lot of organic matter,” he says, “and as the temperature rises and the ice melts, the carbon trapped within it might be slowly released into the atmosphere.” Given this development, the professor decided to grasp this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to pinpoint how this increase in carbon sources creates “negative feedback” which further exacerbates the problem. CUHK’s Faculty of Science, which contains the professor’s department, contains a machine which can perform Fourier-Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry. This machine, capable of producing the highest-resolution readings in Hong Kong, can analyse with great precision the chemical composition of samples, and he hopes to bring some back from Antarctica to demonstrate the shift in carbon levels in recent years.

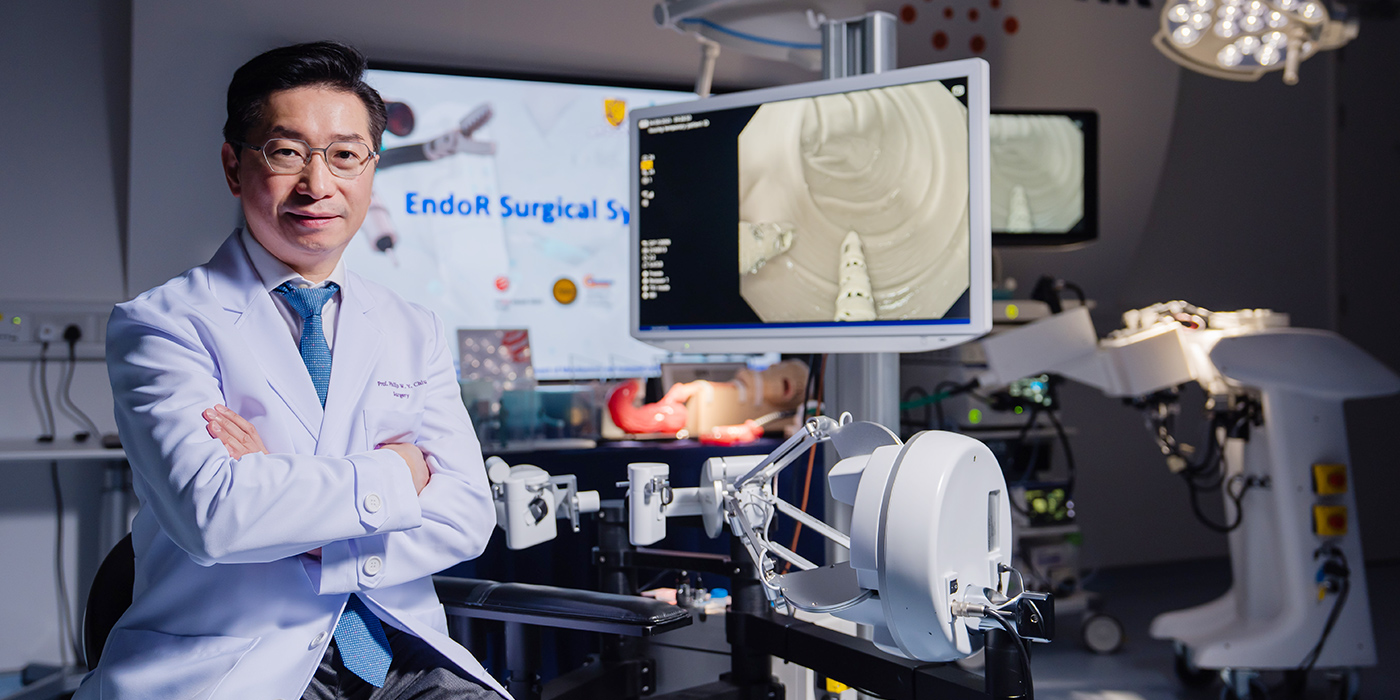

Like Professor Chow, Professor Pittman is also fascinated by the organic matter trapped within Antarctic ice — which might seem surprising, given that he is best known for his work in palaeontology. But according to the professor, his previous experience studying dinosaurs also applies in the frozen south. “The ice contains dissolved minerals and rock powder, and there’s a lot of microbial activity going on,” he says. With his groundbreaking laser-stimulated fluorescence (LSF) technology, an imaging technique that has previously revealed hidden anatomical structures in fossils, he hopes to uncover the wealth of material trapped within the ice. “The transparency of ice means that the lasers can penetrate further into the subsurface,” he adds. “We hope to use LSF to connect small samples of ice, traditionally taken at a handful of points, with chemical information across large areas available through LSF.”

His colleague at the School of Life Sciences Professor Tsui, on the other hand, is more concerned with how the melting of the icecaps might have negative implications on a global scale. His research focuses on mercury and the harm it does to the environment, and the retreating permafrost in Antarctica raises the alarm for him. The Antarctic Great Wall Station, where he will be stationed during the expedition, is situated in the northernmost part of the continent, where rapid greening has been observed recently. “These plants could absorb the mercury in the atmosphere and transfer it down into the soil of Antarctica, potentially toxifying the land,” the professor says. Having conducted similar research in forests and marshes around the world, he is anxious to see the extent of mercury pollution in the hitherto unblemished southern continent.

A delicate balancing act

With so many scientists crowding into Antarctica to conduct their own polar research, a debate has emerged about the negative impact that all these expeditions have on the environment: not only do they disturb the wildlife living there but maintaining a polar base also leaves behind an appreciable carbon footprint. With that in mind, how would the professors weigh the needs of scientific development against its environmental costs? Professor Tsui, whose speciality is environmental pollution, believes that scientists are acutely aware of the delicate balancing act involved, adding that those in the Antarctic “would be particularly cautious about the environmental implications”. He also suggests that given the size of the southern continent, the pollution generated by scientific research can be contained much more easily.

The other scientists agree that while their research efforts might infringe upon the pristine environments of the frozen south, the results will be a net positive. Professor Chow likens the idea of research in the Antarctic to a physical examination. “Injections and blood samples are quintessential components of a check-up,” he says. “And there’s inevitably going to be a bit of pain, but you end up with marvellous data about the entire human body, and you can take steps to prevent further developments.”

‘Research is not a one-way street’

The three professors all voiced their delight at being invited to join an Antarctic expedition. Although other scientists from this city have visited the South Pole before, this is the first time that academics have been involved in an official capacity. The professors are hopeful that this change in landscape will allow them to broaden their knowledge and, in the long run, pass on that knowledge to their students. “Sustainability is an important factor in CUHK’s development,” says Professor Chow. “This expedition marks an important stride, not just for us but also for the University’s polar expertise, as well as in its environmental obligations.”

The other professors are equally buoyant about the opportunity to exchange their knowledge with scientists from the mainland. “Research is not a one-way street,” says Professor Pittman. “The best science always comes from teamwork. So we’re going to use this chance to work with people from places all over the world, and use that to push forward our own scientific developments here in Hong Kong.”

By Chamois Chui

Photos by Keith Hiro