The foresight of the UK’s first female vice-chancellor

Professor Nancy Rothwell’s trailblazing journey in science and academia

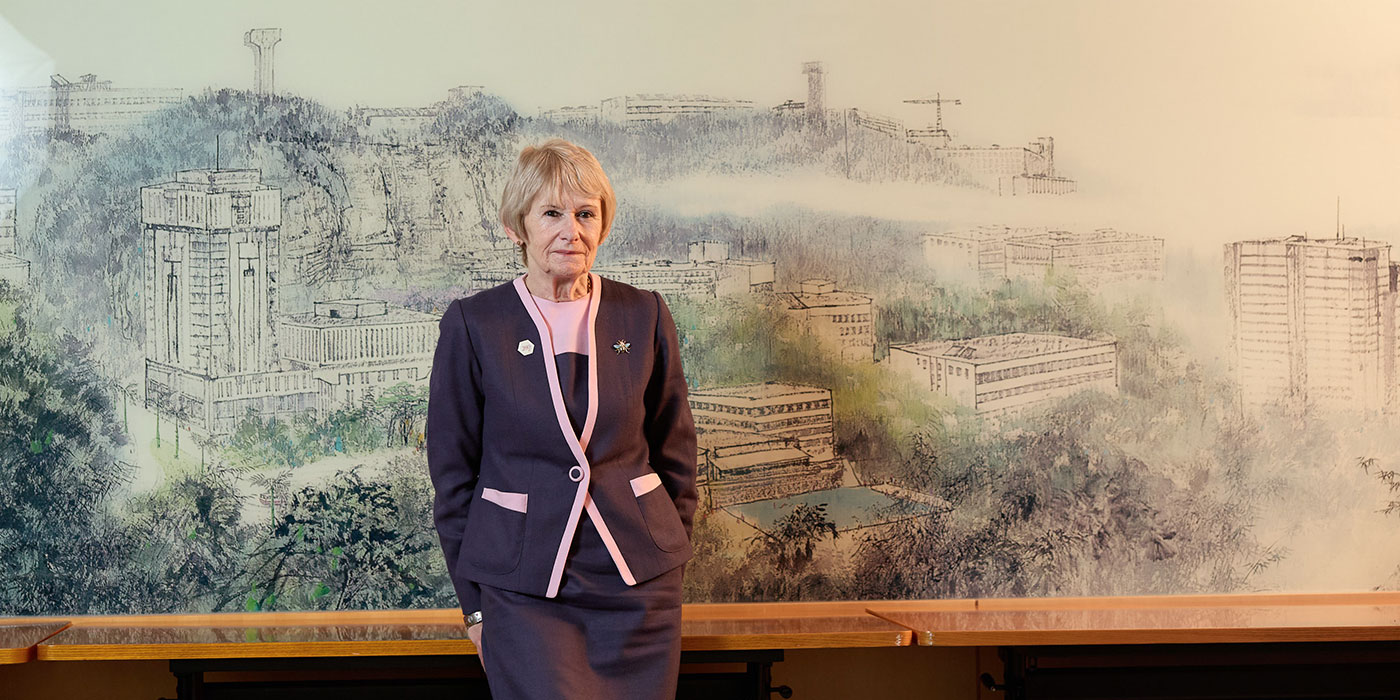

Graceful and confident, dressed in a purple suit adorned with two symmetrically placed pins on the lapels, Professor Dame Nancy Rothwell walked briskly to the interview venue without a sign of tiredness, despite her packed schedule during her short stay in Hong Kong. Her vigour helps to explain her high-flying career, working as the UK’s first female vice-chancellor with great distinction for 14 years.

At the conferment ceremony on 13 November, CUHK conferred on her an honorary doctorate in laws. The former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Manchester has made significant contributions to the understanding and treatment of brain damage from stroke and head injury. Apart from her research endeavours and public science engagement, she has also chaired the prestigious Russell Group of British universities. Even after her tenure at Manchester ended in July, she continues to play an ambassadorial role, continually helping its fundraising efforts and external relations.

From her childhood in rural Lancashire to becoming one of the UK’s longest-serving female vice-chancellors, her trajectory is a testament to the power of passion and perseverance.

The road less travelled

Professor Rothwell’s career path has not been hindered by the under-representation of women in academia and science – although when she turned up at a conference in London as a young scholar, the organisers looked stunned. They supposed she was a man, given her publishing track record in the field. “But generally, I haven’t really encountered barriers. Since there are so few woman scientists in physical sciences, people remember you.”

Across the world, only 17% of the top 200 universities in the Times Higher Education international rankings are led by women. The landscape of academic leadership has been shaped by uneven expectations: women often feel they should not apply for a position unless they meet every requirement, while equally qualified men are more inclined to take the leap and submit their applications.

When she was urged to apply for the position of Vice-Chancellor in 2010, she took up the challenge due to her passion and affection for the university. “I wanted to make sure the university is in good hands.” She went on to oversee a community of 50,000 students and staff and an annual budget of £1.3 billion, with significant growth in student numbers, research income and the fabric of the university.

From strength to strength

During her tenure at the university, it raised £273 million in philanthropic income and committed £250 million in new funds to support leading research, capital projects and transformative scholarship programmes. Professor Rothwell has been a committed advocate for philanthropic initiatives that have greatly influenced Manchester’s growth and success, such as the establishment of the Alliance Manchester Business School, the expansion of Manchester Museum and the Whitworth Art Gallery, and the addition of a visitor centre at Jodrell Bank Observatory, which earned UNESCO World Heritage Site status.

Her tenure has also been distinguished by the development of the university’s green spaces, as well as the university’s rise to second place in the world this year for its commitment to social responsibility and sustainability. The latter includes concrete action to achieve net zero by 2038: for example, a solar farm will produce 65% of its electricity needs when it opens in autumn 2025.

(source: The University of Manchester)

Academic synergy with CUHK

The University of Manchester has a long-standing relationship with CUHK. “We share academic excellence in medicine, climate change, history and culture which are remarkable,” Professor Rothwell says. Both universities have been working closely in regenerative immunology, and Manchester is engaged in CUHK’s Centre for Perceptual and Interactive Intelligence, established as part of the InnoHK initiative.

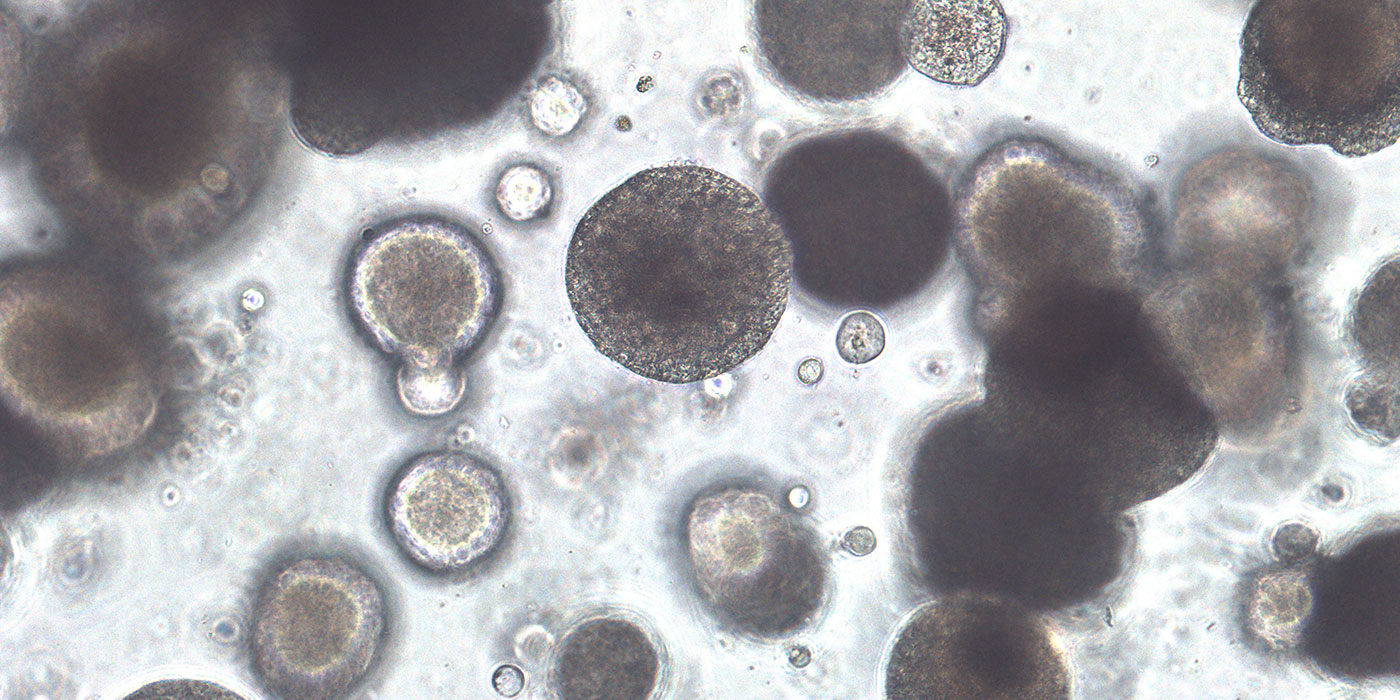

CUHK and Manchester offer a joint research fund comprising a seedcorn fund and a strategic research fund to foster research collaboration on various scales. Seedcorn funding has been awarded to 15 projects, promoting collaboration in areas including cancer, energy and climate change, future cities and tissue engineering, while the strategic research fund has made awards to three projects in translational biomedicine, and the environment and sustainability.

Last year, the two universities established a range of teaching and research collaborations, including the launch of a study option that allows students from CUHK’s School of Biomedical Sciences to earn both a Bachelor of Science degree at CUHK and a Master of Science degree at the University of Manchester in four years, the latter spent in Manchester in either Infection Biology or Tissue Engineering for Regenerative Medicine.

On tenacity and serendipity

Professor Rothwell’s rare blend of academic acumen and creativity can be traced to her childhood in rural Lancashire, where she was surrounded by nature and influenced by her father, an eccentric biologist who filled their home with fascinating scientific props. This environment sparked her curiosity about the natural world, even as she initially struggled with biology at school and gave it up at the age of 14.

She toyed with the idea of a career in art, before realising that she was unlikely to make a living from it – although she did help to support herself by drawing and selling cartoons as a doctoral student.

After completing a research dissertation in her third year, she knew her future lay in academia. She attained a first-class degree in physiology in 1976 and completed her PhD in just two years. Her early research identified mechanisms of energy balance regulation, obesity and cachexia, also known as wasting syndrome.

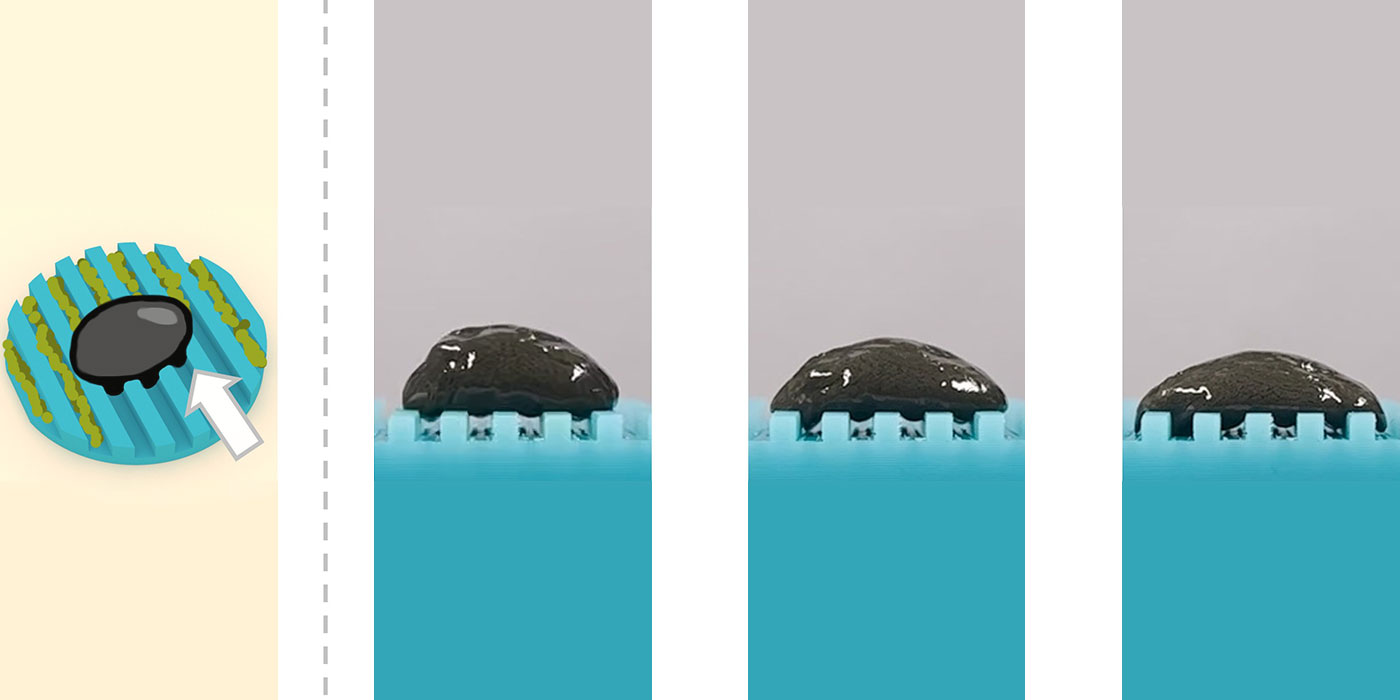

Yet in 1987 she did something rare in science: she set off on a new path, in neuroscience. This was prompted by her unexpected discovery that the protein molecule interleukin-1 (IL-1 for short), which she had found to trigger weight loss during infection and disease, was also active in the brain’s response to strokes and other injuries. Moreover, it could be controlled through the IL-1 blocker that occurs naturally in the body and has been manufactured synthetically as a drug to treat arthritis.

She remained rigorous in research throughout her tenure as a senior leader. Having patented the use of IL-1 inhibitors to prevent acute neurodegeneration, she initiated the first clinical trial of their use in stroke treatment.

Beyond her administrative duties, Professor Rothwell is a passionate science communicator. She gained prominence for delivering the Royal Institution’s Christmas Lectures in 1998 and has held numerous advisory roles across various scientific organisations. Her charisma and commitment to public engagement have made her a sought-after figure in both academia and the media.

Carpe diem

As she transitions to Professor Emeritus and Ambassador for the University of Manchester, she retains the vigour of her student days, when she juggled captaining the women’s rugby team, playing darts, spending three nights a week doing bar work and holding down a part-time job in a market garden.

Professor Rothwell thinks university life is essential for whole-person development, allowing students to explore their multifaceted potential and learn to communicate with people from diverse backgrounds. “Time is invaluable. Be bold and seize the opportunities for personal enhancement.”

She has dedicated her efforts to building strong, lasting relationships with Manchester’s stakeholders, ranging from the local community to international alumni. Regularly visiting groups worldwide, she celebrates the contributions of alumni to both the student experience and social responsibility initiatives. Her legacy continues to inspire future generations of scientists and leaders.

By Jenny Lau

Photos by Keith Hiro