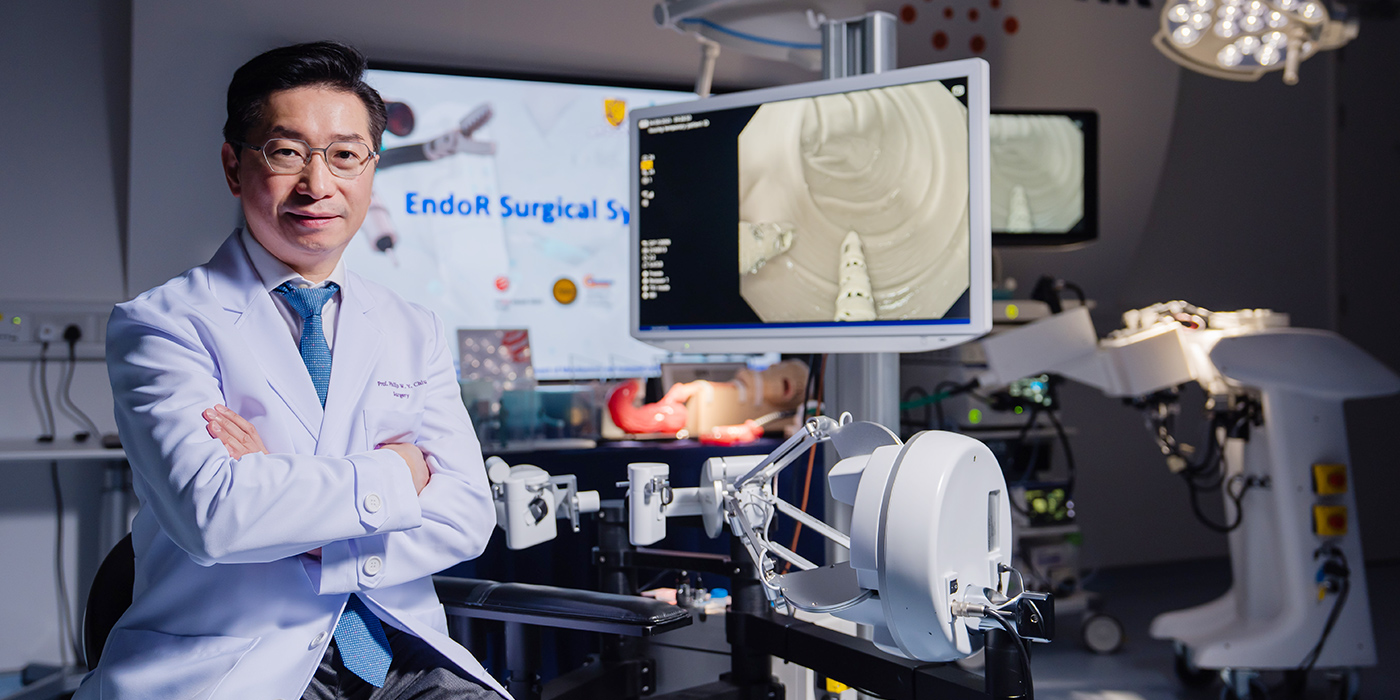

Global eminence in medicine

Victor Dzau has built a career on empathy and health equity for the downtrodden

When Victor Dzau was five years old, his family fled Shanghai for Hong Kong in the aftermath of World War II. “We gave up everything when we left China, a family of five starting a new life in a single room. And do you know? We had neither a bathroom nor a kitchen at that time,” the clinician-scientist says of life in the early 1950s.

This shaped his years of growing up, from a sheltered childhood in Shanghai buttressed by the family’s prosperous chemical manufacturing business, to the hardships of Hong Kong. His parents’ difficult decision to abandon all they had produced in return a front-row seat to the struggles of squatter living. Those memories of poverty, and of his grandparents grappling with tuberculosis, would go on to define his understanding of public health and society.

Healing hearts

Now aged 77, the professor who has called Hong Kong home for years is serving as President of the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) of the United States. He also received a Doctor of Science degree, honoris causa, from CUHK last month in recognition of his outstanding contributions to cardiovascular disease research and vital leadership in advancing public health.

“My childhood experiences have profoundly influenced my thoughts on medicine, hygiene, poverty and helping others,” Professor Dzau tells CUHK in Focus, reflecting on how those formative years inspired his lifelong dedication to medicine and the pursuit of health equity.

In the early days of his career, there were no effective treatments for hypertension or heart failure. Motivated by the needs of patients, he decided to devote himself to cardiovascular drug research, particularly in developing angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors to be used as medicines for treating hypertension and heart disease. The work benefited millions around the world, as did his pioneering of gene therapy for vascular diseases.

Ever grateful for the opportunities that led to his achievements, Professor Dzau is similarly appreciative of CUHK’s conferment of the honorary doctorate on one who had been raised in Hong Kong from the age of five. His connection with CUHK dates back several decades to his time in New York, where he met Dr Edgar Cheng Wai-kin, a former council chairman of CUHK. With Dr Cheng’s encouragement and support, Professor Dzau initiated NAM’s first International Health Policy Fellowship Program in 2018, enabling CUHK scholars to receive training at the US academy. He praises CUHK for its research excellence and looks forward to potential collaborations in cancer, cardiovascular disease and artificial intelligence.

Healing society

Technological innovation alone cannot resolve the fundamental issues that threaten public health, the way Professor Dzau sees it. His childhood struggles instilled in him a deep understanding of the interplay between health and socioeconomic conditions. He believes that without comprehending how patients’ living environments affect their bodies, effective prevention of recurrent illnesses remains elusive.

The scientist does not confine himself to the laboratory, embodying his motto: “From bench to bedside to population to society.” His philosophy is reflected in many initiatives launched by NAM under his leadership, such as the Commission on a Global Health Risk Framework and efforts surrounding women’s health. He encourages young physicians to venture beyond hospitals into communities to promote disease prevention.

“Look at all the great discoveries in AI and genome editing. I think medicine is going to change very much in the next 10 years,” he notes. “The real question is no longer whether we have the capability to improve treatments, but whether everyone can access these technologies. What about the poor people? This is really important.” Professor Dzau envisions a future where medicine aims to cure, prevent and manage all diseases. However, he stresses the equal importance of addressing issues such as equity, big data management and technological risks to ensure that all demographic groups can safely share the benefits of scientific progress.

Healing amid adversity

Professor Dzau’s remarkable achievements did not come easily. He recalls that in the 1960s, Hong Kong had only one medical school, admitting just 60 students each year. Unable to secure a place, he travelled all the way to Montreal, Canada, to pursue his studies at McGill University. “The local people spoke in colloquialism. The language and the culture were very difficult. I had to undergo a difficult adjustment,” he says, recalling how he suspended his education after his wife fell ill.

Nonetheless, Professor Dzau persevered through the many challenges and later secured a position at Harvard University as a postdoctoral research fellow, which paved the way for his illustrious career. He has served as president and chief executive of the Duke University Medical Center and co-chair of the Global Health Summit Scientific Expert Panel established by the Group of 20 and the European Commission. In 2014, when he was appointed as President of the Institute of Medicine, the predecessor of NAM, he was the first ethnic Chinese to lead the body, and also the first among the US national academies.

In a light-hearted moment, Professor Dzau quips about the adversities that drove him abroad. “If Hong Kong had had a medical school that accepted students with degrees from McGill, I would have come back.”

He then turns serious. “You don’t always succeed. You have to understand that failure is part of life. It is important not to be too discouraged or depressed when you fail, but to cultivate resilience. You have to pick yourself up, keep going and keep trying.

“Another lesson for me has been in finding purpose in life, what I call the ‘North Star’. Focusing on patients and creating a better society are, to me, very important purposes.”

Looking ahead, Professor Dzau suggests that Hong Kong’s exploration of establishing a third medical school adopt the American “4+4” model, which combines four years of undergraduate education with four years of medical training. This approach could attract high-calibre students from diverse academic backgrounds, thereby avoiding competition with existing medical schools while creating more opportunities for top local students who study overseas to return to their home city, he says.

From a difficult period of youth to his stature as a leader on the international research stage, Professor Dzau shares three secrets of success: striving for excellence, aspiring to innovation and seizing opportunities. He believes that a supportive and open system that encourages boldness and innovation will help the Chinese community continue to shine and make significant contributions to the world.

By Jessica Chu

Photos by D. Lee