The past living in the present

Cecilia Chu retells the Hong Kong story by tracing its century-long speculative urbanism

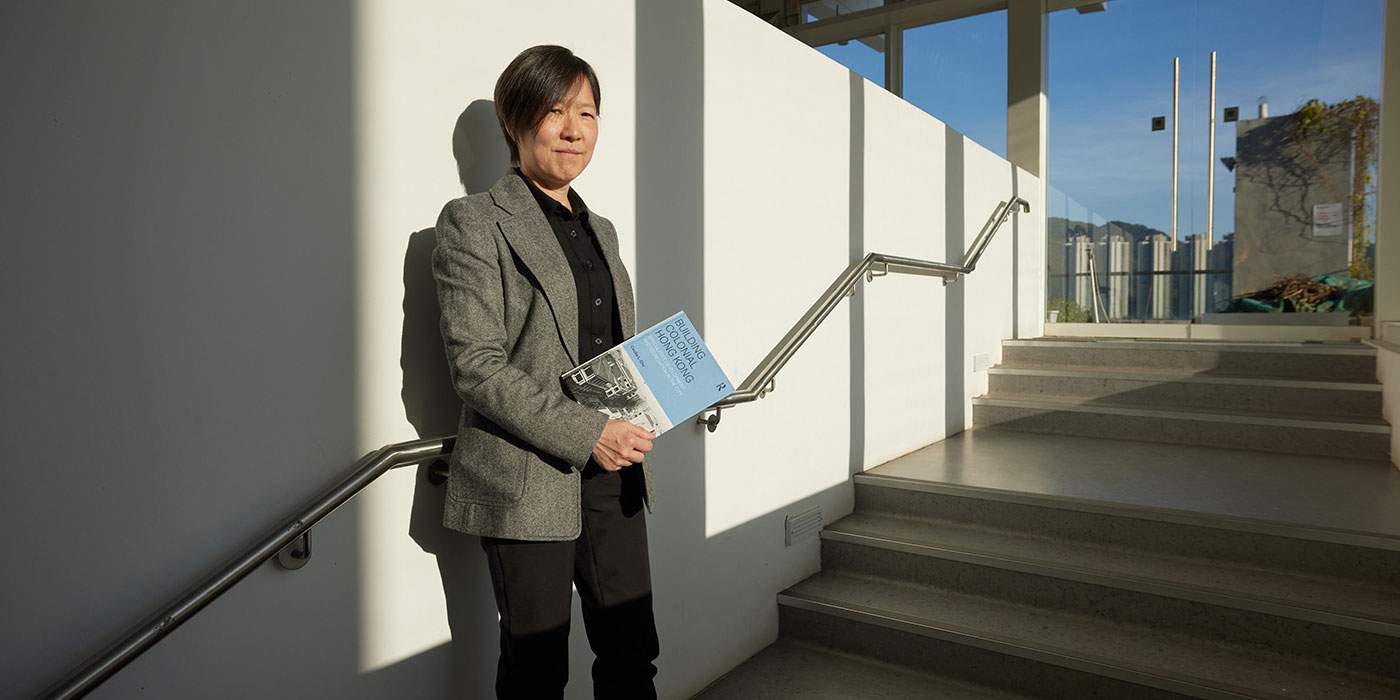

Many scholars refer to official documents for historical analysis, but Professor Cecilia Chu prefers to explore ordinary people’s perspectives from correspondence and mass media material such as newspaper supplements and magazines.

“All these records vividly reflect diverse perspectives of the people living in the colonial city. I’m very interested in how historical discourse has been constructed through multiple, hybrid narratives,” the urban historian says in an interview with CUHK in Focus.

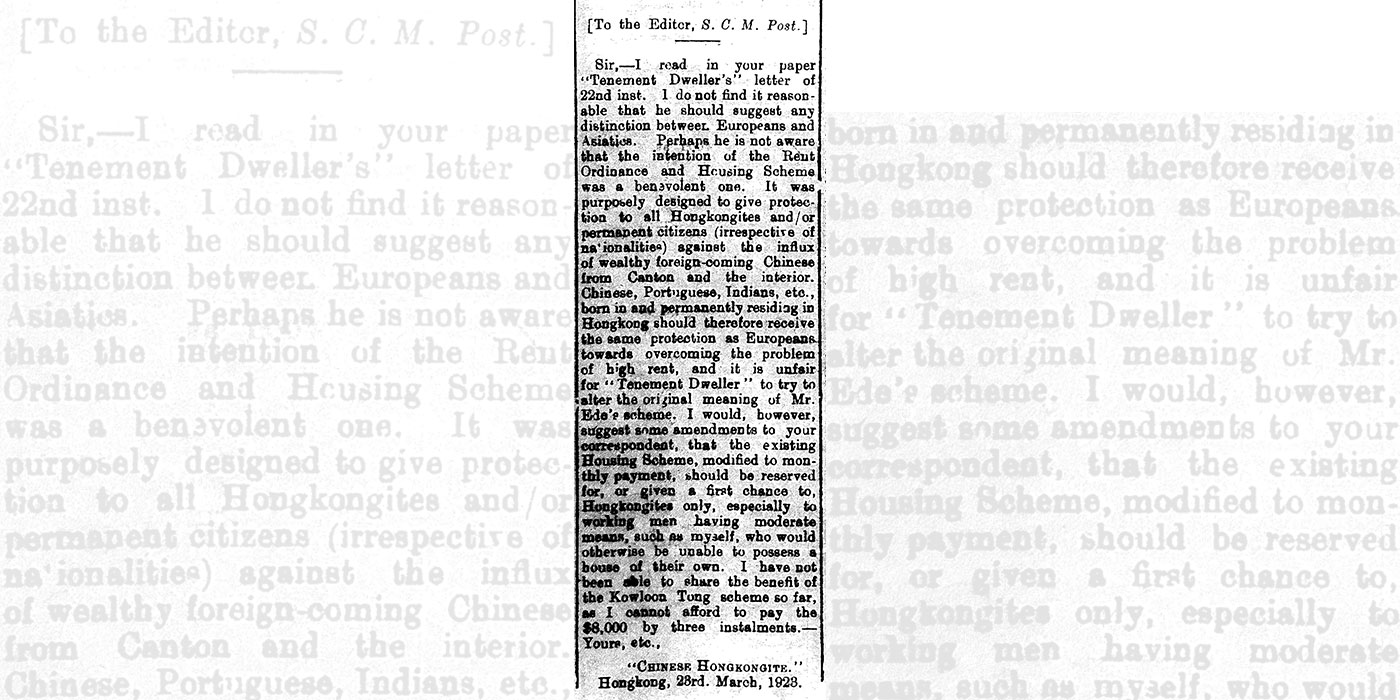

As she found out – to her surprise – the trend of non-local investors fuelling Hong Kong property prices was singled out as early as the 1920s, when the media published many letters to the editor on this issue. These include, for example, a letter to the South China Morning Post (SCMP) signed “Chinese Hongkongite” critical of two sources of housing speculators.

There were the mainland Chinese immigrants flush with cash, but also the Europeans, whom the letter contributor argued should not have the sole privilege of living in segregated zones.

“Chinese, Portuguese, Indians, etc., born in and permanently residing in Hongkong should therefore receive the same protection as Europeans towards overcoming the problem of high rent,” said the contributor, who further suggested that the proposed affordable Housing Scheme (previously featured in the newspaper) “should be reserved for, or given a first chance to, Hongkongites only, especially to working men having moderate means, such as myself, who would otherwise be unable to possess a house of their own”.

Professor Chu, of CUHK’s School of Architecture, was inspired by this letter and other historical material when she worked on her award-winning monograph, Building Colonial Hong Kong: Speculative Development and Segregation in the City. Published in 2022, it traces the development of Hong Kong urban planning from the 1880s to the 1930s and analyses the advent of the city’s speculative urbanism and its impact on social disparity.

The records showed that early last century, Hong Kong people were already thinking about their identity and resisting outsiders who were blamed for driving up property speculation. “If you came across this letter today, you might not have recognised it as something that happened 100 years ago. This phenomenon is very interesting.”

Deep dive into unofficial archives

By examining several pivotal case studies crystallised from myriads of historical sources she collected in Hong Kong, the UK and other cities, the professor highlights the conflicting logic of colonial urban development: promoting native investment to support a laissez-faire property market while simultaneously enforcing the segregation of communities based on their race within a hierarchical, colonial spatial order.

Professor Chu’s monograph has garnered two prestigious international book awards: the 2023 Best Book in Non-North American Urban History of the Urban History Association and the 2024 International Planning History Society Book Prize. Both prizes were the first for any book about Hong Kong, marking historical milestones in the academic pursuit of Hong Kong history and Hong Kong studies. “It’s truly my honour to be recognised by two leading academic institutions in urban history and planning history,” she says.

High land prices: Hong Kong’s historical trajectory

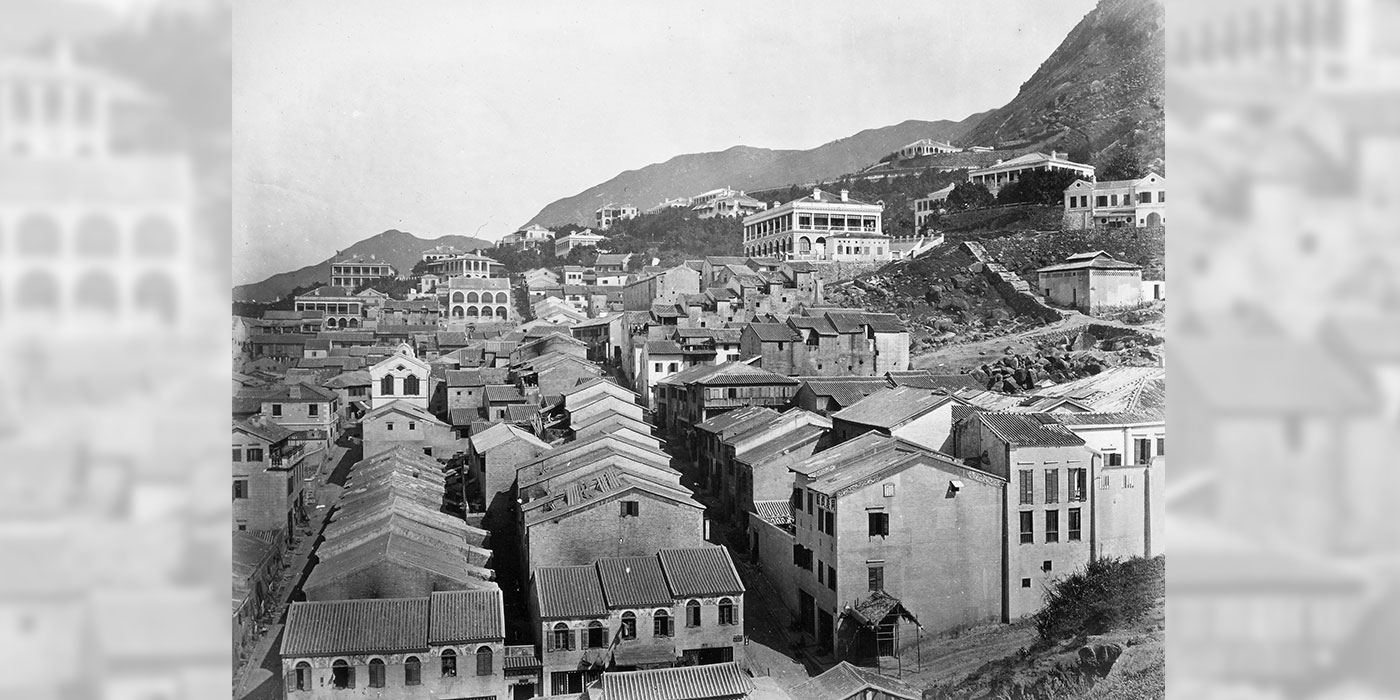

Hong Kong in the 1880s thrived as a bustling colonial entrepôt. The city was home to many Europeans, particularly the British, who resided in luxurious mansions in Mid-Levels and The Peak while most Chinese migrant labour packed themselves like sardines into overcrowded tong lau in Tai Ping Shan.

Tong lau, that quintessential abode of the underprivileged masses, was a type of Chinese tenement built with wooden structures, green brick walls and pitched tiled roofs. It was typically characterised by back-to-back construction, which dimmed illumination and choked ventilation. But despite the persistent inequality and poor living conditions, Hong Kong continued to draw various classes of sojourners and immigrants who ended up living in these buildings, all seeking to improve their social status by amassing wealth, particularly through land and property speculation.

Since the 19th century, most of the revenue of the Hong Kong colonial government’s coffers had come from land sales under a policy of high land prices, a practice that exists to this day. The biggest problem was how to increase revenue and reduce expenditure, as the British government was not responsible for any of the colony’s finances except military costs.

Speculation of Chinese tenements

Tong lau contrasts against the Western-style residences known as yeung lau. The difference between tong lau and yeung lau was that the former could be subdivided into multiple compartments, whereas the latter was to be rented only to one family and could not be sublet. Naturally, most rich landlords wanted to invest in tong lau for higher rental returns.

“Tai Ping Shan was very popular among investors because of the high rental revenue it generated, despite its nasty and dilapidated appearance,” says Professor Chu. Although the construction of tong lau was inspired by the bamboo building tradition in Guangzhou , property owners transformed the Hong Kong version to accommodate more tenants and make more money from rents. Every building had around three to four floors accommodating five or six households per storey, a layout that confined each family to the size of a cubicle room, with only enough space for beds and a poor hygienic environment where tenants would keep poultry.

When the bubonic plague broke out in 1894 on Tai Ping Shan, the overcrowded and unsanitary tong lau exacerbated the health crisis. In response, colonial officials mandated the inclusion of larger windows and a height restriction of four floors, and also prohibited back-to-back constructions, to improve living conditions and prevent the spread of diseases. Back-to-back tong lau eventually disappeared, except for a few isolated examples, such as the one on 120 Wellington Street, which formerly housed Wing Woo Grocery.

On nostalgia and social justice

A native of Hong Kong, Professor Chu went to Canada when she was 14 and returned at the age of 25, only to up sticks again to pursue doctoral education in the US. “I have much affection for Hong Kong, but in fact I have not lived in Hong Kong for half of my life,” she says.

It was in Canada that she began to think about the established concepts of ethnicity, race and gender. “I feel that my in-between identity, of not being purely a Hongkonger, a Canadian or an American, has aroused my quest of seeking to find out how identity is constructed and how people interpret heritage,” she says. Her cultural encounters have empowered her to analyse Hong Kong from a new perspective and in a more dispassionate manner.

As an urban historian with expertise in design and conservation, the professor examines the sociocultural dynamics that shape built environments and their impact on community , with a focus on Asia and Hong Kong. She explores the intricate relationship between spatial design, representation and the creation of social meaning, specifically, how professional and public understanding of architecture and landscapes contributes to urban development and shapes collective societal goals.

She has been critical of the prevalent attitude toward heritage conservation, which tends to romanticise the past with a strong sense of nostalgia. She thinks that the situation is problematic because it prevents people from developing a critical reflection on Hong Kong’s complex colonial history.

“We shouldn’t only praise the old and beautiful tong lau and perceive these buildings as a source of nostalgia or tourist attraction, while forgetting the sufferings of the people who lived there more than a century ago and even being oblivious to the fact that after 100 years, there are still many people living in subdivided units in Hong Kong,” the urban historian adds.

To Professor Chu, conservation is not only about preserving the structure of a building, but also about interpreting its stories and multiple social meanings. “What does the built environment represent? What is the historical significance of those buildings? What are the continuities and discontinuities in the past and present? And can these spaces be used to foster social betterment in the city?” The questions go on. And the quest today remains pressing.

By Jenny Lau

Photos by Keith Hiro