A sensor-ble solution

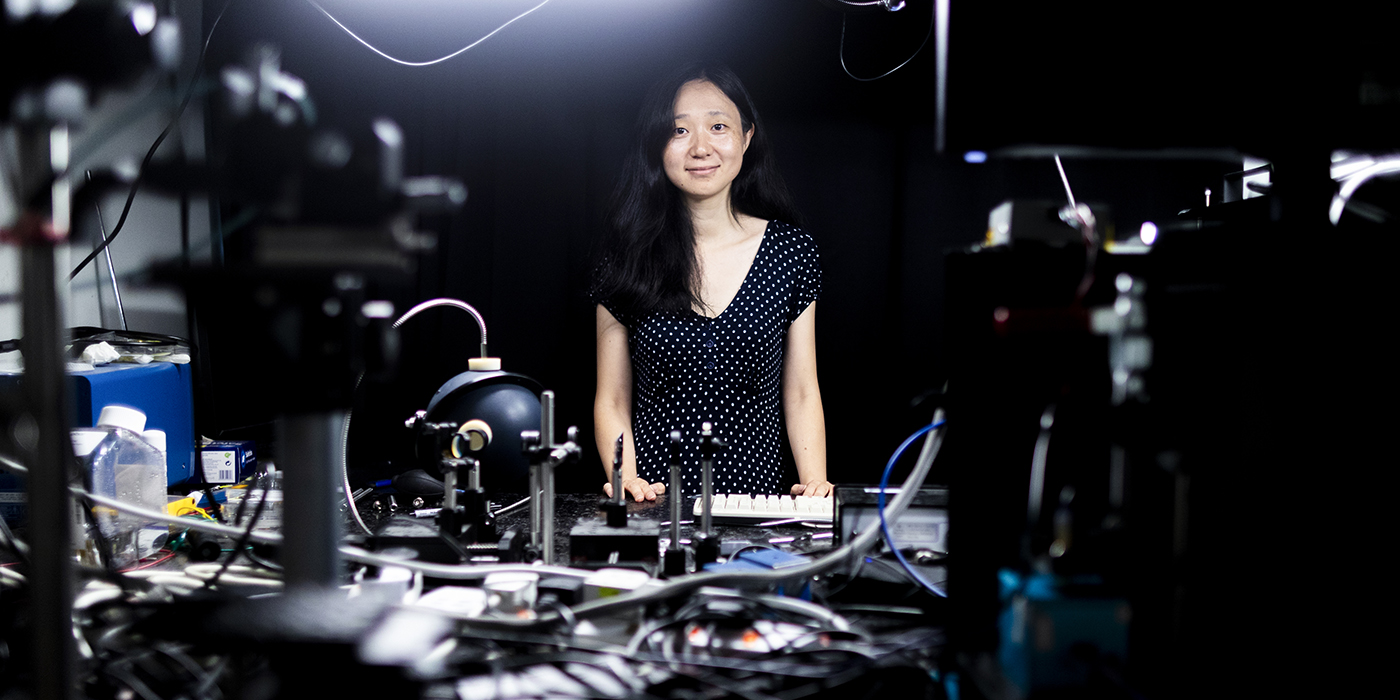

Engineer Zhao Ni’s journey towards wearable medical devices for all

This is the third in our series of CUHK in Focus articles which talk to principal investigators of the seven CUHK projects chosen for the Hong Kong government’s Research, Academic and Industry Sectors One-plus (RAISe+) Scheme. The scheme seeks to help local universities transform and commercialise their research and development (R&D) outcomes, and provides funds, on a matching basis, of up to HK$100 million to each approved project.

Of all the factors that matter in Zhao Ni’s research, the one she returns to the most is utility. “We are in the discipline of engineering,” says the professor of Electronic Engineering, “and a shared value in this discipline is that we should develop useful technology.”

This focus on utility most recently culminated in Professor Zhao’s proposal being chosen by the RAISe+ scheme. Her research hopes to improve the detection of cardiovascular diseases (CVD), and funding from the scheme will support her team’s research on wearable medical devices that monitor vital signs, enabling personalised artificial intelligence (AI) to tell the user how their body is doing.

If this sounds like it can replace a trip to the clinic, the professor is quick to stress that the use of AI will not threaten the medical profession. “Our goal isn’t to replace doctors, but to offer more immediate help to patients, particularly those with CVD, who want to know their situation better. We also aim to equip doctors with more comprehensive information, so that they can better track and understand the progression of the disease.”

The human in the machine

“I have always had engineering in my blood, in my genes,” says Professor Zhao. “I wanted to do physics more on the experimental side, you know, not very theoretical.” Her life in academia has long been characterised by this pursuit of utility: as a young student of materials sciences and engineering at Tsinghua University, she was fascinated by new scientific breakthroughs announced in the media from time to time. It was the ability to apply what she had learned that captivated her, all the way to a PhD specialisation in optoelectronics, the study of devices that utilise light, at Cambridge University. From there she took up a post-doctorate fellowship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where she deepened her research.

CUHK became her next career move after she read an article about the University in the South China Morning Post. The young professor took up a faculty position at the Department of Engineering, and during a conversation with a colleague, Professor Zhang Yuan-Ting, she came up with the idea of looking into how flexible electronics such as sensors might benefit healthcare. “I had never worked on sensors before I came to CUHK,” she says, and yet the research which resulted from that chat ended up finding favour with the steering committee of the RAISe+ scheme.

Healthcare in two parts

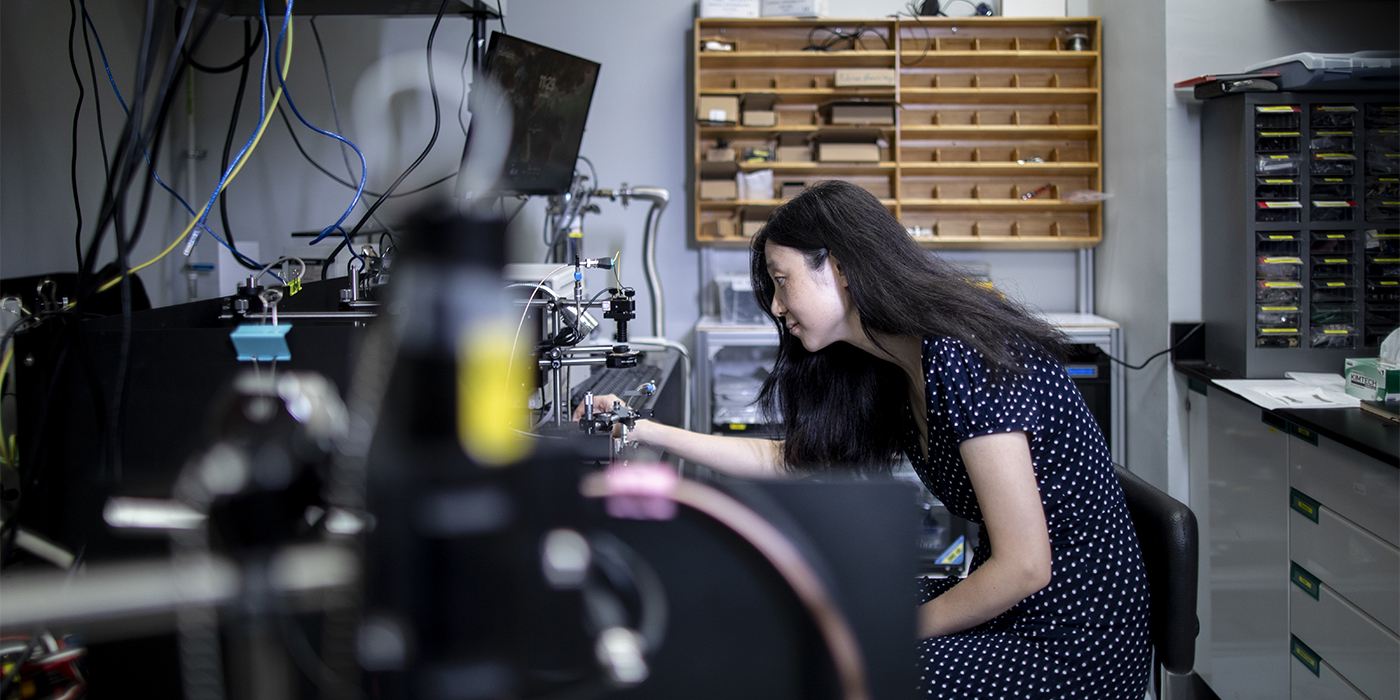

This research project consists of two components. The first is a series of wearable medical devices, developed by Professor Zhao and her team to track risk factors of CVDs in the body. “These wearable sensors can collect all the necessary vital signs, including heart rate, blood oxygen level, and blood pressure; but also some other parameters that may be less familiar to the public, like arterial stiffness.”

All this data is then fed into the second component: a personalised AI system that Professor Zhao has referred to as “Dr. PAI”. This system, she explains, “combines the beauty of generative AI models with the most advanced sensing technology”. Generative AI models, the most famous of which is ChatGPT, draw on vast amounts of information to generate their own responses; Professor Zhao’s new system similarly processes the wealth of data collected from the various connected devices to create feedback to the user, advising them on health issues and steps they might want to take to minimise medical risks. “The more you interact with your own model, the more the model learns about you,” she says.

Professor Zhao is eager to point out how Dr. PAI might complement traditional healthcare. Although citizens of Hong Kong can receive medical attention with relative ease, this is not the case for many people around the world. “In areas that have very limited hospital resources,” she says, “it’s very difficult to arrange an appointment with doctors, and in Hong Kong, it’s also the case in public hospitals.

“So before the appointment, you can have some sort of intermediate method to understand your situation, and adjust your lifestyle or change the dosage of medication if necessary.”

Keeping the faith in the next generation

For Professor Zhao, developing projects such as Dr. PAI for general use is a natural extension for academics. “When I was in MIT,” she says, “the coolest thing among students was not which professor had published a paper or whatever. It was about whoever had started a company, received investment, and gotten a very cool product.” She feels passionately about the necessity of turning the fruits of one’s research into something that can help the community and humanity at large. “The existence of [research] fields like sensors is because of need: if we cannot deliver anything that can be useful in the end, this field would die! So to keep people having faith in this field, we have to have successful commercialisation.”

This is an ethos that she has maintained over a decade and a half of research. In her capacity as Vice-Chair (Graduate) of the Department, she oversees a vast cohort of postgraduate students and directly supervises a large group of budding academics. “When I supervise students, I spend more time on the first-year students, because that’s when I encourage them to look for new projects, new directions for their PhD,” she says. She does not cast aspersions on their hopes and dreams, but is eager for her mentees to “slowly understand the value of research” and how it might be turned towards practical purposes.

One can be sure her focus on utility never wavers. “Impossible is fine,” she says. “Because if something’s very useful, maybe you can do your impossible projects! But we should also analyse, from the scientific side, whether it’s theoretically possible.”

By Chamois Chui

Photos by LCT

All the articles of our RAISe+ Scheme series can be found here:

- Samuel Au powers the future of healthcare with cutting-edge technology

- Barbara Chan endeavours to use tissue engineering to heal patients

- Lam Hon-ming pioneers sustainable agriculture through soybean research

- Liu Yun-hui drives robots with 3D-vision

- Tsang Hon-ki on moving from lab to market

- Raymond Yeung innovates in network technology for a smarter future

- Engineer Zhao Ni’s journey towards wearable medical devices for all